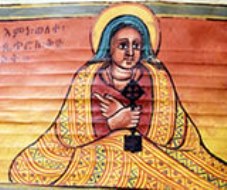

Walatta Petros (B)

Saint Walatta Petros (Ge’ez: ወለተ፡ጴጥሮስ, Wälättä P̣eṭros, 1592–November 24, 1642) is one of thirty women saints in the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church and one of only six of these women saints with hagiographies. She was a religious and monastic leader who led a revolt against Roman Catholicism, defending the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church when the Jesuits persuaded King Susənyos (1572-1632) to proclaim Roman Catholicism the faith of the land. Her name means “Daughter of [St.] Peter.” Her followers wrote down the story of her life about thirty years after she died, in 1672, with a monk in her monastery named Gälawdewos serving as the community’s amanuensis (this hagiography has been translated into English).

She was born in 1592 into a noble family, her mother was named Krəstos ˁƎbaya (In Christ lies her greatness) and her father was named Baḥər Säggäd (The [regions by the] sea submit[s] [to him]). Her father adored her, treating her with great reverence and predicting that bishops and kings would bow down to her, giving her the name of the man upon whom God built his church, Peter.

She was married at a young age to Susənyos’s chief advisor, Mälkəˀä Krəstos (Image of Christ). After all three of her children died in infancy, she grew tired of the things of this world and determined to leave her husband to become a nun. Not long after, in 1612, Susənyos privately converted from the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church to Roman Catholicism, and over the next ten years, he urged those in his court, including her, to convert as well, finally delivering an edict banning orthodoxy in 1622. When Walatta Petros first left her husband, around 1615, he razed a town to retrieve her and she returned to him so that more people would not be harmed. Then she discovered that her husband had been involved in the murder of the head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church and she again determined to leave her husband, starving herself until he let her go. She immediately went to a monastery on Lake Ṭana and became a nun at the age of 25, in 1617. There she met, for the first time, Ǝḫətä Krəstos, the woman who became her constant companion in life and work and the abbess of her community after Walatta Petros’s death.

Walatta Petros lived quietly as a devout and hard-working nun and might have remained as such if the king had not banned orthodoxy. Her hagiographer reported that she did not want to keep company with any of the converts, so she took several nuns and servants and fled her monastery, going 100 miles east of Lake Ṭana to the district of Ṣəyat. There she began to preach against Roman Catholicism, adding that any king who had converted was an apostate and accursed. The king soon heard of these treasonous remarks and he demanded that she be brought before the court. Her husband and powerful family came to her defense, and so she was not killed, but was sent to live with her brother in around 1625, on the condition that she stop her teaching.

However, she soon fled him (taking the same nuns and servants) and moved from Lake Ṭana to the region of Waldəbba, about 150 miles north, which was then drawing many monks and nuns who refused to convert and were fomenting against the new religion. While there, Walatta Petros had a vision of Christ commissioning her to found seven religious communities, a charge she only reluctantly took up. She left and went to the region of Ṣallamt, east of Waldəbba, and again began preaching against conversion. The angry king again called her before the court, and this time she was sentenced to spending Saturdays with the Jesuits, as the head of the mission, Afonso Mendes, worked to convert her.

When this was unsuccessful, the king banished her, alone, to the Ethio-Sudan borderlands, Žabay, a hot and barren place. There she endured many hardships, but many monks and nuns who did not want to convert found her and became members of her community. Due to the kindness of the queen, Ǝḫətä Krəstos was allowed to join her. Thus, Žäbäy was the first of the seven communities prophesized. After three years the king relented and she went with her followers to live in the region of Dambəya, on the northern side of Lake Ṭana, setting up her second community, Č̣anqʷa. More men and women followed her there, and when sickness broke out, she moved her followers to Məṣəlle, on the southeastern shore, her third community.

Finally, in 1632, fifteen years after Walatta Petros had become a nun, a disheartened Susənyos rescinded the conversion edict and died just a few months later. Walatta Petros was revered as a heroine for her resistance to early European incursions in Africa. For the next ten years, Walatta Petros’s community continued to grow and the next king, Fasilädäs, looked on her with great favor. She set up her communities at Dämboza, Afär Färäs, Zäge, and Zäbol. Then, after a three-month illness, she died, twenty-six years after she had become a nun, and was buried at the monastery or Rema on Lake Ṭana.

In 1650, Fasilädäs gave land to establish her monastery at Qʷaraṣa, on Lake Ṭana, which remains her monastery today. Walatta Petros’s fame continued to grow over the next century, and her monastery became an important sanctuary for those fleeing the wrath of the king, for whom she performed many miracles, as recorded in her hagiography.

Unfortunately, the edition of her life published in 1912 was based on one manuscript, and that very corrupted, so most of the research about her published before the recent English translation and edition, based on twelve manuscripts of the hagiography, contains incorrect information about her life. Typical errors in previous works were stating that her hagiography was written in Afär Färäs; that all three of her children were sons; that she was born in 1594; that she died in 1644; and that she went to Aksum.

Wendy Laura Belcher

Bibliography:

Anonymous. 1910. Annales Regum Iyasu II et Iyo’as. Edited by Ignatius Guidi, Corpus scriptorum christianorum orientalium 61: Scriptores Aethiopici 28: Textus. Paris; Leipzig: E. Typogropleo Republicae; Otto Harrossowitz.

Appiah, Anthony, and Henry Louis Gates. 2005. "Walatta Petros." In Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience: Second Edition, 336. New York: Basic Books.

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2013. "Sisters Debating the Jesuits: The Role of African Women in Defeating Portuguese Cultural Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century Abyssinia." Northeast African Studies 12:121-166.

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2016. "Same-Sex Intimacies in the Early African Text the Gädlä Wälättä P̣eṭros (1672) about an Ethiopian Female Saint." Research in African Literatures (June).

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2016. “The Kings’ Goad and the Rebels’ Shield: Legends about the Ethiopian Woman Saint Walatta Petros (1592-1642)” History Today (summer) www.historytoday.com.

Belaynesh Michael. 1977. "Walata Petros." In The Encyclopedia Africana Dictionary of African Biography, edited by L. H. Ofusu-Appiah, 141-142. New York: Reference Publications.

Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. 2003. "Creating an Iconographic Cycle: The Manuscript of the Acts of Wälättä P̣eṭros and the Emergence of Qʷäraṭa as a Place of Asylum." In Fifteenth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, 409-416. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. 2008. Les îles de la mémoire. Fabrique des images et écriture de l’histoire dans les églises du lac Tana. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

Chernetsov, Sevir. 2005. "A Transgressor of the Norms of Female Behaviour in the Seventeenth-Century Ethiopia: The Heroine of The Life of Our Mother Walatta Petros." Khristianski Vostok (Journal of the Christian East) 10:48-64.

Gälawdewos. 2015. The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros: A Seventeenth-Century African Biography of an Ethiopian Woman, translated and edited by Wendy Laura Belcher and Michael Kleiner. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gälawdewos. 1970. Vita di Walatta Piēṭros. Translated by Lanfranco Ricci, Corpus scriptorum christianorum orientalium 316; Scriptores Aethiopici 61. Leuven, Belgium: Secrétariat du CSCO.

Gälawdewos. 1912. Vitae Sanctorum Indigenarum: I: Acta S. Walatta Petros. Edited by Carlo Conti Rossini, Corpus scriptorum christianorum orientalium 68; Scriptores Aethiopici 30. Rome, Paris, Leipzig: Karolus de Luigi; Carolus Poussielgue Bibliopola; Otto Harrassowitz. Reprint, 1954.

Gundani, P. H. 2004. "Christian Historiography and the African Woman: A Critical Examination of the Place of Felicity, Walatta Pietros and Kimpa Vita in African Christian Historiography." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 30 (1):75-89.

Hastings, Adrian. 1994. The Church in Africa: 1450-1950. Oxford New York: Clarendon Press: Oxford University Press.

Papi, Maria Rosaria. 1943. "Una santa abissina anticattolica: Walatta-Petros." Rassegna di Studi Etiopici 3 (1):87-93.

This article, received in 2016, was written by Dr. Wendy Belcher who is associate professor of African literature in Princeton University’s departments of Comparative Literature and African American Studies. With Michael Kleiner she authored the translation of The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros: A Seventeenth-Century African Biography of an Ethiopian Woman (Princeton, 2015).