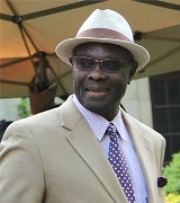

Sanneh, Lamin

On Sunday, January 6, 2019, Professor Lamin Sanneh of Yale University passed away at the age of 76. He grew up in humble circumstances along the Gambia River in West Africa in an Islamic community, yet he died as a Christian associated with one of the most prestigious institutions of learning in the West, Yale University. He was the D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School, Professor of History at Yale University, and Director of the Project on Religious Freedom and Society in Africa at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale.

He was an extraordinarily gifted African scholar. He became a leading historian in the study of World Christianity, missions, and the little understood place of the local vernacular in Bible translation and its cultural implications. He provided a radical revision of and challenge to the received understanding among professional historians as to the role of Western missions, particularly in Africa. [1]

The goal of this tribute is to highlight the enormous contribution that Lamin Sanneh made to our understanding of the Bible translation enterprise. The particular audience for this tribute are those involved one way or another in the Bible translation movement. To set the context, I will track his development from childhood to his conversion followed by the period of his intellectual development in various university-level study programs. This context should deepen the reader’s appreciation for the insight that Sanneh brought to the Bible translation ministry. Much of what I present here I took from his autobiography Summoned from the Margin: Homecoming of an African (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2012).

Childhood, Conversion, and Baptism: From Spiritual Struggle to Peace

Lamin Sanneh was born into the world of the Mandinka in the Republic of the Gambia in West Africa. He was the son of a Mandinka chief. It was an Islamic context with regard to family and community. No Christian witness existed nearby. However, when he and other bright children went off to secondary school, mission school alternatives were available, though Sanneh only attended government schools.

He carried himself with a confident humility and gentleness. He was not self-promoting in contrast to what he would often find in the academic world of the West. He was also courageous, willing to question the received wisdom of the day when he perceived the given wisdom to be wrongheaded. He was a man of peace serving between the Islamic and Christian worlds in Africa.

Growing up in an Islamic context and family, he gained a strong theocentric orientation to life. As he wrote, he “learned to honor God.” [2] This orientation never left him. He also grew up in an African community, with its sense of group solidarity and the importance of the group over the individual. As he wrote, “In the world in which I grew up, individual thoughts and feelings had a marginal role.” [3]

At the school of Qur’anic instruction for children, Arabic was clearly the language for faith and worship. It was sacred and treated as absolute, while the vernacular, Mandinka, was treated as not being worthy for matters of faith or worship or prayer. His response to the Islamic context was to become a pious child.

Sanneh proved to be religiously precocious as a child. He would say that religion was his first awakening thought, wondering about the mystery of the universe. He wondered about the Muslim teacher and his devotion to the Qur’anic text, about the five daily prayers, and about what really pleased God. These questions led to moral inquiry about the meaning of God, a moral life, and God’s self-revelation. He first heard about Jesus in the Qur’an and was intrigued with how God “rescued” Jesus from the cross. He wondered about suffering and about Jesus.

These thoughts pursued him throughout secondary school. Near the completion of secondary school, he gained employment in Banjul, the capital of the Gambia. The questions about Jesus, suffering, and pleasing God continued and he pondered them at length. One day, taking a stroll along the seaside, he was compelled “to follow Jesus as the crucified and risen One.” [4]On reaching home, he fell to his “knees in prayer to Jesus, pleading, imploring, begging for God to forgive me, to accept me, to reach me, to help me – everything a child looks for.” [5] The “sense of struggle, fear, and anxiety vanished.” He felt a “release and freedom, infused with a sense of utter, serene peace. I could speak about it only in terms of new life, of being born again.” [6] He explained to a friend that he was not “abandoning Islam, but … [I] had learned as a Muslim to honor God, and now I wanted to love God. Islam had not repelled me; only the Gospel had attracted me.” [7] For some time he sought baptism without success. Finally, in June 1961, a Methodist missionary agreed to baptize him.

Sanneh now realized he needed to learn about Christianity. In seeking to satisfy this need, he demonstrated that he was researcher at heart and he would find books to be his best resource. In fact, he came to love books. Most of his classmates abandoned reading after secondary school, treating it as a child’s activity. Sanneh by contrast found his way to the British Council Library. He read books from a variety of authors, from Bertrand Russell to C. S. Lewis. His critical and theocentric mind could appreciate the brilliance of Russell but also sense the contradictions in his philosophy of life and ethics. Lewis became a sage counselor for him and a crucial voice about matters of Christian faith. At some point, he even wondered if he should be a missionary to his own people, the Mandinka. Just before graduating from the Gambia High School, he traveled to Germany at the invitation of an American traveler that he met in Banjul. In Germany, he could see “Christian decline all around,” but it became “clear that the study of religion should determine the contribution I might make in life.” [8]

Worthy of note is that Sanneh had become a Christian in the era when African colonies were beginning to gain their political independence. The common wisdom in the world of academia in the West at the time was that once European colonial powers liberated their African colonies, any Christian Africans would abandon their Christian religion, a religion imposed on them by the colonial powers and Western cultural imperialists—or so academics thought. No one could foresee that the opposite would happen. Hundreds of millions of Africans would become Christians in the next six decades. Sanneh was an early convert in this mass movement to Christianity.

Sanneh, now on a trajectory to grow in his understanding of his Christian faith and where it fit in the larger world, was about to pursue university education in the West. He would be entering a world where most university professors were not theocentric, where individualism had replaced social solidarity, and where Christianity came in more varieties than the Catholic and Methodist churches found in Banjul. In addition, the Protestant churches in the USA for the most part had not resolved the question of race, many participating in racism either intentionally or unwittingly, and often compromised by political commitments that were treated as equal to or even as surpassing the commitment to the Triune God. Thus, he would discover a domesticated Christianity, American style. Sanneh would have to process these matters for the next fifty years of his life while still carrying within him the orientation and values of his upbringing in the Gambia.

Off to the USA, Europe, and the Middle East: A Season of Intellectual Development

Sanneh obtained a scholarship to study in the USA and arrived in August 1963. Civil rights, the Viet Nam War, and Free Speech were all issues in American society and on campuses. Concerns for the environment were embryonic but being raised and the Peace Corps started operations. He began his studies in Virginia at a mostly black college and finished the last three years in New York. Throughout these years, he wanted to find a church home, a faith community where he was accepted, but it was a struggle. At university, he received his bachelor’s degree in History even though he was disappointed in his thesis on the abolitionist movement of the eighteenth century. In the process, he learned that he was fascinated with “issues of movement and change in society,” that is, with history. He also learned that his strong interest in religion was not only a matter of theology but also of history. The study of the two, religion and history, were compatible areas of learning.

For a person who considered being a missionary to his own people, and even more seriously wanted to study theology as the next step in his faith journey, these two options never received support from others. Therefore, he began searching for what to do next. No one in the Gambia was asking him to return, so he looked elsewhere, such as to Asia, with possibilities of studying Japanese or Chinese history. However, a trusted friend recommended that he should engage in Islamic Studies because of his knowledge of Arabic. Wanting to study theology but discouraged by others at every turn, he now could combine the study of religion with the study of history in the study of African Islam. He would never have selected this area for graduate research earlier, but ironically and providentially, his major contribution to our understanding of Christian history would flow from this field of study.

To pursue such studies, Sanneh set out to improve his Arabic and begin researching African Islam. He traveled to Nigeria and then Britain. Among his developing findings were that colonial administrations favored Muslims by controlling or minimizing missionary influence and supporting Muslim institutions. Christian missions had to struggle against both the colonial administrations and indigenous Muslim hostility until independence came. Sanneh had seen such action in the Gambia. He also found it in Nigeria and Sudan. Therefore, as colonies gained independence a major obstacle to Christian missions, namely the colonial administration, disappeared. The reality of this phenomenon challenged the Western academic assumption that colonial institutions imposed Christian faith on the people of Africa. In reality, the colonial administrations were trying to block missions.

To complete his fact-finding he traveled to Beirut in the summer of 1968, just after the Six Day War. He concluded his travel with a period of service in Nigeria to engage with Christians in their dialogue with Muslims. The result was that in the spring of 1971 he enrolled in the PhD program at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. Another result of this period is that Sanneh developed a set of professional friends in the guild of historical research that would sustain him over the coming years. One particular significant point of interest in his research in Africa was the presence and history of a Muslim pacifist movement, in which they were committed to tolerance and the peaceful rather than the coercive establishment of an Islamic society. He completed his PhD in 1974 and followed it with lecture appointments in Britain, Sierra Leone, and Ghana.

The Scandal of the Vernacular: “God” in Indigenous Language

In September 1978, Lamin Sanneh and his wife moved to Aberdeen, Scotland. Sanneh had accepted the university’s offer of an academic position. It was here that he gained Andrew Walls as a close colleague and developed an enduring friendship with Jonathan Bonk. He arrived in Aberdeen with his specialization in Islam and the history of Islam in Africa and expected to be teaching on Islam. However, the department also needed someone to teach about African Christianity. The person who normally taught the subject was on sabbatical. Sanneh was initially reluctant to teach the course, but he relented.

As he prepared for the course, he said that the material on Christian missions “stumped” him. In Islam, the use of Arabic for God’s revelation was absolute, the language of the founder was central to worship, and God was only known by one name. In contrast, the Christian missions’ material testified to a different phenomenon. Christian missions translated their revelation, the Bible, into the local vernacular, the local language. They even used the local word for “God.” They did not bother themselves with the language of the founder. Muslims would never even think of doing such a thing. Sanneh says he was dumbfounded.

The assumptions he carried with him from his intimate knowledge of Islam and from his education in the guild of Western historians had no conceptual space for such an activity. By translating the Christian Scriptures, as Sanneh saw it, missions were “ceding strategic ground to the vernacular.” [9] The local language and local culture became the interpretive context for knowledge of the Christian God. The process relativized the original languages of the Scripture texts, as well as the language of its founder. Faith and worship did not depend on one language at the foundation of the religion. As Sanneh summarized his finding: “Christianity is a form of indigenous empowerment by virtue of the vernacular translation.” [10]

This phenomenon immediately called into question the received wisdom of Western historians who were committed to the claim that Western missions were a form of cultural imperialism. Instead, as Sanneh discovered, Western missions actually pursued a form of cultural affirmation. Sanneh recognized that he had a choice: caution or courage. He could either remain silent or face the guild of historians with the shocking truth that “ethnic self-preservation” had an advocate in the phenomenon of Bible translation. The implication was that this activity was hardly a form of cultural imperialism, but a form of upholding local languages and cultures. Of course, some of those historians who would not move from their assumptions on missions could move the discussion from language to the fact that the content of the translation was imperialistic. Yet, as Sanneh recognized, who else esteemed the local vernaculars around the world to such an extent? The rhetorical answer was “no one.”

In the next year, British politics and economics began to undermine the welfare of British universities, so Sanneh ended up taking a position at Harvard University and its Center for the Study of World Religions. This proved providential. Sanneh’s Harvard colleagues were open to the thesis he was developing about the vernacular and Christian missions. It was all the encouragement he needed. Aberdeen was the “origin and stimulus” but Harvard was “the catalyst for the idea that native tongues launched and accompanied the Christian movement through its history.” [11] Koine Greek was an example to which C. S. Lewis had pointed him. In contrast, Muslims do not translate the Qur’an. Worship, devotion, and witness do not depend on the vernacular, only on Arabic. Any translation of the Qur’an is viewed as a commentary. It is not inspired or sacred text whereas for Christians the translated text, such as Scripture in English, is canonical. [12]

For those involved in Bible translation it is common to refer to the motivation for translation as making the text “understandable” for the intended audience. However, as Sanneh notes, the use of the vernacular not only has a utilitarian basis but also is of divine significance since the text carries the universal message of the good news in Jesus Christ. In addition, Bible translation often leads to other affirmations of the status and worth of the vernacular and therefore the peoples speaking those languages. Many of these affirmations come in the form of a material impact. Sanneh summarized the material impact of this positive orientation to the vernacular: “The most tangible expressions of this vernacular impulse are the orthographies, grammars, dictionaries, and other linguistic tools the Western missionary movement created to constitute the most detailed, systematic, and extensive cultural stocktaking of the world’s languages ever undertaken.” [13]

This would include the other benefits such as literacy and educational materials, and social benefits such as recognition by government institutions as a “real” language. In addition, the expansion of Scripture engagement and the ethno-arts only increased access to the vernacular through multiple forms of media (print, audio, video, electronic, and storying) and various vernacular forms such as music, dance, and drama. Many of the contributions of this kind are represented in SIL International’s Ethnologue with its listing of over 7,000 languages and the SIL Bibliography containing tens of thousands of articles and materials concerning these languages.

Eventually, Sanneh published his thesis and research in Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (1989, 2nd edition 2009). The thrust of the book was that Western Christianity resulted from a similar process of vernacular translations similar to what is happening today in non-Western contexts.

Conceptualizing the Growth of the World Christian Movement

Another conceptual space that Sanneh helped develop was that concerning the growth of the worldwide Christian movement. Again, the Western academic world seemed unaware of what was happening outside the West. They only focused on Christianity in the West, and many were celebrating its demise in the post-Christian West. However, beyond the Western world, the two-thirds world was the arena of a growing Christian population, particularly in Africa and Asia. It was the developing of a post-Western Christian world. It was “post-Western” in that the colonial powers were no longer in control of Africa and Asia and Christianity did not come with colonial power but now came only with its truth claims, and where the local name for God is used instead of one from the dominant language. He described this phenomenon in Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity (2008).

After a couple years at Harvard, Yale University invited Sanneh to take the Chair of World Christianity. He accepted. The remainder of his career was at Yale University and Yale Divinity School. Three important consequences of Sanneh’s insights remain today. First, Sanneh reported, “missionary translation has now become a familiar topic in many academic fields,” with one strange exception – it has not entered the world of academic theology. Second, Sanneh’s insights have affirmed and buoyed those involved in Bible translation. They were committed to their service and its utilitarian rationale, and Sanneh provided even greater socio-historical support for their service. Third, the University of Ghana, Accra, has agreed to house an institute focused on the study of religion and society in Africa. They named it the Sanneh Institute. Therefore, Sanneh’s life will continue blessing others in multiple ways.

Lamin Sanneh experienced a life filled with irony. He learned to honor God through the Islamic piety of his youth but came to love God through his conversion to Christianity. He gained a PhD in African Islamic history as a Christian but it opened the door for him to become a leader in the study of world Christianity. He recognized the absolute nature of Arabic in Islamic revelation but demonstrated to the world that Christian missions favored the vernacular because Christian revelation could be canonical in any language. Western historians trained him to accept the assumption that Christian missions was a matter of cultural imperialism but he proceeded to teach them that Christian missions involved the affirmation of the local culture and language. He grew up along the banks of an African river in humble circumstances but spent most of his adult life as a professor at one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, Yale University. Sanneh recognized the incongruities of his life. He sensed that the progression in his life was more than the conscious choices he made but were a witness to the loving hand of God carrying him through his life.

Many will greatly miss him. His reputation and influence will likely increase over the coming years, as his insights and wisdom become more widely known. While we mourn the loss of Lamin Sanneh, one for whom being at home in the family and in a faith community was of a high existential and metaphorical value, we can celebrate with him that he has now experienced his final homecoming into the presence of the God he loved. [14]

John R. Watters

Notes:

- Eulogies by close friends can be found at: Christianity Today In addition, Jonathan Bonk, the Project Director of the Dictionary of African Christian Biography, promises a full tribute in the future. DACB tributes can be found at What’s New? Archive - “An African Giant has Died: Lamin Sanneh”

- Lamin O. Sanneh, Summoned from the Margin: Homecoming of an African (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2012), 103.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 56.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 102.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 102.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 102.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 103.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 119.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 217.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 217.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 222.

- For example, at the dedication of the Ejagham New Testament where I was involved in December 1997 the Director of the Cameroon Bible Society held up a copy of the New Testament and exclaimed in a loud voice, “This is the Word of God for the Ejagham people.” He had strongly affirmed the canonical status of the Ejagham New Testament. Of course, every Sunday morning churchgoers affirm the canonical status of the vernacular translations of the Bible into English, Spanish, German, French, Chinese, etc.

- Sanneh, Summoned, 225.

- The author has served with Wycliffe Bible Translators and SIL International for 48 years. He served as linguist-exegete in the Ejagham New Testament translation program in Cameroon and Nigeria, and assisted in Bible translation in various other ways over the past 48 years. He first met Lamin Sanneh in 1996 and crossed paths with him multiple times over the next twenty-two years in various venues. He has a B.A. in History from the University of California, Berkeley, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Linguistics from UCLA.

Suggested reading:

Sanneh, Lamin. Beyond Jihad: The Pacifist Tradition in West African Islam. 1st edition. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press, 2016. (Author’s note: See the review of Beyond Jihad by John Azumah in the IBMR journal, 41.4, 2017. Azumah is from Ghana and also a Muslim background Christian, Professor at Columbia Theological Seminary, Decatur, Georgia, USA.)

———. Disciples of All Nations : Pillars of World Christianity. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

———. Summoned from the Margin: Homecoming of an African. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2012.

———. Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2009.

———. Whose Religion Is Christianity? The Gospel beyond the West. Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2003.

This biography, received in 2019, is re-published with permission from SIL International Communications. The author, Dr. John R. Watters, is Special Advisor to the Executive Director, past President of SIL International and Wycliffe Bible Translators International, and also former Africa Area Director for SIL International.