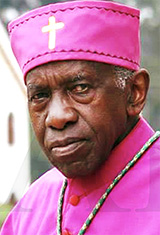

Ndingi, Raphael S. (Mwana a’Nzeki) (B)

Introduction

Raphael Simon Ndingi Mwana a’Nzeki is the former Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Nairobi and the former head of the Catholic in Kenya. He was also the bishop of Machakos and Nakuru Dioceses. He is believed to be one of the church leaders who played a significant role in the Kenya’s second liberation struggle. During President Moi’s era, which was infamous for dictatorship, oppression and exploitation, Ndingi fearlessly fought for the rights of Kenyans and the restoration of human dignity.

Early Life, Education and Journey to Priesthood

Raphael Ndingi Mwana a’Nzeki was born on December 25, 1931 in Minyanyani Sub-location, Mwala location, Machakos County. Although his birth during Christmas did not attract the attention of his kinsmen, the Akamba, who were still traditionalists, later assessors came to connect his birth to that of our savior because of the role he played of liberating Kenyans and fighting for human rights (Gathungu, 2021). His determination to fight for the rights of the downtrodden was seen during the 1991-1992 tribal clashes in Kenya, when he courageously led a delegation of Catholic bishops and National Council of the Churches of Kenya leaders to President Moi at State House in Nairobi to protest against the killing and displacement of innocent people (Githiga, 2001). The message they delivered to the president showed Ndingi’s real nature:

As religious leaders we have to tell you plainly that you are wrong in your assessment of the situation. Whether you like or not, the truth is that the people have lost confidence in you and in those close to you. At present you seem to be securing the interest of a small clique of rich and powerful men who are surviving at the cost of the life, blood, and misery of thousands of small people (Gifford, 2009, p.39).

Ndingi was the last born of five children. His parents were Maria Muthoki and Joseph Nzeki Ngila. His siblings were Paul Muli, Veronica Kavenge, Ann Muluu, and Teresia Katunge (Gathungu, 2021).

During Ndingi’s early childhood, western education had not been introduced to the Kamba people as a way of bringing up their children. The Akamba’s main source of livelihood was raising livestock. The boys thus took care of the livestock, while the girls were involved in domestic chores. Ndingi therefore looked after his father’s cattle. The colonial government made it mandatory for every household to provide one son to go to school, or pay a penalty of one cow. In order to escape the fine, Ndingi’s father, Mr. Nzeki volunteered his first son, Paul Muli for school. When Muli refused to go, this opened the way for Ndingi to acquire education. Mr. Nzeki gave the alternative of the other son who was Ndingi (Cheney, 2020).

Ndingi joined Minyanyani Holy Ghost Primary School in 1937 and, in 1940, transferred to Kabaa Primary school (Musyimi, 2023, OI). He was at Kabaa Primary school when a plague hit the area in 1940. This forced the students to stop their studies and the school was closed for three years. Thousands of students, priests and nuns perished but Ndingi escaped from the illness unaffected (Kitonyi 2023, OI). In the same year (1940), he transferred to Etikoni Primary School and completed his primary education in 1944 (Musyimi, 2023, OI).

The following year (1945), he joined Kabaa High School for his secondary education. He completed his two-year secondary education, form one and two in 1946. (Musyimi, 2023, OI). In 1948, he joined Kilimambogo Teachers’ College and graduated with a Primary 3 (usually referred to as P3) teacher certificate in 1950. After a short stint as teacher, the young Ndingi enrolled as a student at Kibosho Seminary in Moshi, Tanzania in 1952, majoring in philosophy. In 1955, he joined Morogoro Senior Seminary in Tanzania for theological studies. With this, he qualified for ordination to the priesthood. He was ordained priest at Kabaa Parish on January 1, 1961 by Archbishop John Joseph McCarthy, archibishop of the Archdiocese of Nairobi at that time. He was the first Kamba to be ordained a Roman Catholic priest (The Standard, 2020).

In 1964, Ndingi registered for Cambridge School Certificate (Ordinary level) as a private candidate, after he was granted permission by the archbishop to complete his secondary education. On the recommendation of Archbishop McCarthy, he won a scholarship which enabled him to join St. John Fischer College, Rochester New York, USA in 1965 to study history and political science. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in History and Political Science in 1969 (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020). Many years later, in 1996, St. John Fischer College awarded him an honorary doctorate in law (Odundo, 2020). He was awarded a State Commendation by the Government of Kenya as Elder of the Order of the Burning Spear (EBS) as a way of appreciating what he had done for this country (Chenye, 2020).

Work and Ministry: Teacher, Priest and Bishop

Ndingi worked briefly as a teacher in 1951. He taught at the newly opened minor seminary at Kiserian under the Archdiocese of Nairobi (Odundo, 2020). In 1963, he was sent to Our Lady of the Visitation Makadara Parish in Nairobi. Later, he moved to St. Peter Claver parish. While serving as priest in Nairobi, he started hostels for young people who did not have a place to stay in the confusing city of Nairobi. Most of these young people had just moved from the countryside and did not know where to stay (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020). During this time, he also served as the Catholic chaplain at Starehe Boys’ Centre and he was also responsible for education in Kiambu District before he was transferred to Tala mission in Machakos (The Standard, 2020; Odundo, 2020).

In 1965, the Kenya Catholic Secretariat appointed him Education Secretary, a position he held up to 1966 (Odundo, 2020). In that capacity, he helped to get Forms V and VI classes started at Mang’u High School and Loreto High School Limuru (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020).

On August 1, 1969, he was consecrated the first bishop of the Diocese of Machakos by Pope Paul VI in Kampala, Uganda (Githiga, 2001). Once again, he made history as the first man from Kambaland to become a bishop in the Catholic Church. He served in the Diocese of Machakos for only about two years and then he was appointed as the first bishop on the newly created Diocese of Nakuru on August 31, 1971 (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020). The Christians of Nakuru were so happy that finally they had a bishop, but those of Machakos were very unhappy with the decision to transfer their bishop. There were protests in Machakos where Christians wanted the decision to move Ndingi to Nakuru halted. The Pope, through the Apostolic Pro-Nuncio, Archbishop Perluigi Sartorelli in Nairobi, refused to change his mind and Ndingi had to move to Nakuru.

Ndingi legally took the diocese on December 31, 1971, and was officially installed as the bishop of the Diocese of Nakuru on January 30, 1972 (Odundo, 2020). His humility and determination to serve were once again exemplified in that, unlike other bishops and leaders who liked to show their might and power, he chose to drive himself all the way from Machakos to Nakuru, a distance of 22.4 kilometers. Unlike other worldly and religious “kings” who enjoy a fleet of cars and a multitude of people, Ndingi went to the new diocese alone, to the amazement of many Christians who were waiting for him (Musyimi, 2023 OI). When he met the Christians of Nakuru, he told them not to overburden themselves with his needs as he was very comfortable with a small allowance just to enable him to serve the diocese (Odundo, 2020).

Ndingi served the Diocese of Nakuru for twenty-five years and he is remembered for many things. Fr. Casmir Odundo sums up the many things Ndingi did for the people of Nakuru. He explains that,

During these years, he did a lot. He built a new cathedral and renovated it when it needed major renovations. He also set up a minor seminary. He opened up many parishes. He was instrumental in the setting up of Kericho diocese as a separate jurisdiction from Nakuru. He also ordained more than 70 diocesan priests for the diocese (Odundo, 2020).

Fr. John Baur states that when Ndingi arrived in Nakuru, he met only one diocesan priest, Fr. Peter Kairo, who had been ordained in 1970. Through his focused leadership, the church population grew from 70,000 to 280,000 in 1989, the parishes from 10 to 36, local clergy from 1 to 3, and native sisters from 5 to 95 (Baur, 1990, p.139). By the time he left the diocese in 1996, these figures had reached remarkably high levels. Ndingi’s success was mainly due to his policy of engaging his co-workers as much as possible. He loved, encouraged and respected his priests, and he oftenly said, “I will support my priests.” The priests and other Church workers reciprocated by loving and supporting him. As a result, the diocese experienced an exponential growth (Odundo, 2020).

Due to Ndingi’s love for the local clergy, he opened his own minor seminary at Molo (St. Joseph Seminary) and wholly supported the seminarians. He was among the few church leaders who were very keen on the indigenization of the church in Africa. This did not however deter him from working with foreign missionaries. During his time, many missionaries—including the Veronica Fathers, the Holy Ghost Fathers, the Donum priests, and the Franciscans—came and set up mission stations in the diocese (Baur, 1990, p.139).

Current church leaders, especially bishops can learn many things from Ndingi related to the management of the church. In the first ten years of his ministry in Nakuru, he focused in the extension of evangelization work. In the next ten years he concentrated on pastoral work. To ensure that he succeeded, he a drew up a “Pastoral Plan” in 1978 in consultation with priests, religious brothers/sisters and laity. The plan covered every aspect of pastoral activity ranging from the organization of prayer houses, parishes, deaneries and diocese (Baur, 1990). The plan was adopted by the Synod as a blueprint for pastoral work in the diocese. This plan was what made work of the bishop very successful in Nakuru. Some of the most memorable things about Ndingi in Nakuru were his contributions to agriculture, such as Baraka Farm, drilling boreholes for the people of God to use, setting up the Diocesan Pastoral Centre and fighting bravely for people who were being mistreated during the well-known tribal clashes (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020).

Ndingi made every effort to build his diocese both physically and spiritually, but it is perhaps his propensity to vigorously and fearless fight for the rights of the people of Rift Valley and Kenyans in general that have made him admired and remembered by many. In fact, some church leaders, like Retired Bishop Gideon Githinga of the Anglican Church of Kenya refer to him as a “Human rights activist” (2001, p. 213). At a time when everyone was afraid to stand up to President Moi, Ndingi led a group of church leaders to tell him that if he (the President) “did not change his policies, the country will not be KANU [the ruling party at that time], but a cemetery of its sons and daughters” (Gifford, 2009). This was during the 1991-1992 tribal clashes in the Rift valley where more than 2000 people lost their lives.

At the height of Kenya’s second liberation struggle, many church leaders supported the KANU government and did not want to participate in the demonstrations that were going on. Some church leaders however chose to be the voice of the voiceless and even developed their own theology of liberation (Gifford, 2009). Ndingi was among the few who decided to speak against the oppression and exploitation that was going on under the KANU regime. Together with him were Bishops David Gitari, Henry Okullu and Alexander Muge of the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) and Rev. Timothy Njoya of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) (Throup, 1995).

In 1988, Moi’s government introduced a voting system known as “Mlolongo” or queue voting, where the voters queued behind the image of their favored candidate. Ndingi was among the first church leaders to oppose this voting system (KDRTV News, 2020)—which, according to Bishop David Gitari, set the stage for massive rigging as candidates with shorter queues defeated the candidates with long queues (Gitari, 1988). Githiga (2001) affirms that most of the Ndingi’s sermons spelled out the social and political dimensions of the gospel. The Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB) eulogized Ndingi as a “fearless man of God who was a thorn in the flesh of the political class” (The Catholic Mirror, 2020).

Whenever there was a problem in the country, Ndingi never minced his words. For example, speaking from his base in Nakuru in 1988, he lamented the killing of democracy in Kenya. The Weekly Review of April 29 quoted him as expressing concern about the future of democracy in Kenya. He was alarmed over a party and a government that was increasingly becoming intolerant of the people’s views and wishes (Citizen Digital, 2020). He is remembered for the active role he played in the struggle for the re-introduction of multiparty democracy in Kenya. Although he was a moderate who tried to avoid pitting the public against the government, the atrocities committed by Daniel Arap Moi’s repressive regime forced him to publicly condemn the authorities (Citizen Digital, 2020).

From Bishop to Archbishop: Ndingi at the Helm of the Catholic Church’s Leadership

On Friday, June 14, 1996, Pope John Paul II appointed Ndingi as the Co-adjutor Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Nairobi. This meant that he would have the right to succeed the Cardinal Maurice Otunga as the Archbishop of Nairobi. Cardinal Otunga was to officially retire a year later (Odundo, 2020). The Christians of Nakuru did not take this appointment very positively. Many felt that it was too early for the bishop to leave them. Besides, others had not known any other bishop apart from Ndingi (Odundo, 2020). Were it not for the fact that he had been promoted, they would have protested just like the Machakos Christians had done. Their grief was evidenced in the way many Christians cried during his farewell service at the diocesan cathedral in Nakuru (Gathungu,2023).

Ndingi was installed at the Coadjutor Archbishop of Nairobi on August 13, 1996. On June 21, 1997, he succeeded Cardinal Otunga as Archbishop (Catholic Hierarchy, 2020). Ndingi’s record in Nairobi speaks for itself (Odundo, 2023). In his ten-year tenure, as the Archbishop of Nairobi, the number of parishes grew from 80 to more than 100. He aslo helped to finance many schools and hospitals. Wherever he did his ministry, he directed funds towards education, training, and jobs. He raised up many professionals, religious sisters, brothers, priests, and bishops. He ordained 56 priests while working at the Archdiocese of Nairobi (Cheney, 2020). Some notable senior leaders ordained by Ndingi include Archbishop Peter J. Kairo, Archbishop Martin Kivuva Musonde, Bishop Urbanus Joseph Kioko, and the immediate former Archbishop of Nairobi, John Cardinal Njue (Citizen Digital, 2020). One of the last memorable things he did as Archbishop of Nairobi was to initiate the beatification process of his immediate predecessor Maurice Michael Cardinal Otunga (Odundo, 2020).

Ndingi retired as the Archbishop of Nairobi on October 6, 2007 after attaining the canonical retirement age of 75 years. He was succeeded by John Cardinal Njue, who was installed as the Archbishop of Nairobi on November 1, 2007 and created cardinal on 24 November 2007.

Life After Retirement: Archbishop Emeritus

After his retirement, Ndingi lived a quiet and peaceful life at the clergy home in Nairobi, where he prayed for and counselled many people who visited him for assistance (Esther, 2020). Very interesting with him was that despite suffering from memory loss due to dementia, Ndingi would still greet visitors warmly and even pray for them (Wambua, 2023).

In April 2008, after the worst post-election violence in the Kenyan history where about 1,133 people lost their lives, at least 350,000 were internally displaced, more than 2000 became refugees, there was unknown number of sexual violence victims, 117,216 private properties were destroyed and 491 government-owned property (offices, vehicles, health centers, schools) annihilated (Kagema, 2017), President Mwai Kibaki appointed Ndingi as the Chairman of the Committee for the Resettlement of the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Citizen Digital, 2020). On July 20, 2008, he celebrated his farewell Mass at Holy Family Basilica and, on August 16, 2008, the Archdiocese of Nairobi held a farewell Mass for him (Odundo, 2020).

Ndingi passed away on March 30, 2020, at the age of 89 years after a long sickness and was buried at Holy Family Basilica, Nairobi on April 7, 2020. He left an indelible mark not only on the Catholic Church in Kenya but in the whole country. It will impossible to erase Ndingi from the minds of the Kenyans in the many years ahead. One question which has remained unanswered for many is why the Roman Catholic Church did not create Archbishop Ndingi a cardinal.

Dickson Nkonge Kagema

References

- Baur, J (1990). The Catholic in Kenya. Nairobi: St.Paul’s.

- Catholic Hierarchy (2020). http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/bishop/bndi.html (accessed on Sept 9, 2023).

- Citizen Digital (2020). https://www.citizen.digital/news/retired-catholic-archbishop-raphael-ndingi-mwana-a-nzeki-dies-after-long-illness-328529/, (accessed on October 4, 2023).

- Cheney, D. M (2020)”Archbishop Raphael S. Ndingi Mwana’a Nzeki [Catholic-Hierarchy]”. catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Esther, M (2020) Lit Kenya, https://litkenya.com/retired-catholic-archbishop-ndingi-mwana-nzeki-dies-at-88/, (accessed on September 19, 2023).

- Funeral Brochure Funeral (2020) compiled by the Archdiocese of Nairobi communication, (accessed on October 2, 2023).

- Gathungu, K. (2021). “Archbishop Ndingi Mwana a’Nzeki Dies at 89.” Daily Nation. Retrieved from https://www.nation.co.ke/kenya/news/archbishop-raphael-ndingi-mwana-anzeki-dies-at-94-3229352.

- Gifford, G (2009). Christianity, Politics and Public Life in Kenya. London: Hurst and Company.

- Githiga, G (2020). The Church as the Bulwark against Authoritarianism. Oxford: Regnum.

- Gitari, D (1988). Let the Bishop Speak. Nairobi: Uzima.

- KDR TV News, I April 2020. Kdrtv.co.ke

- Kitonyi, D (2023) Oral Interview, Machakos.

- Kituu, D (2023) Oral Interview, Minyanyani.

- Odundo, C (2020). Archbishop Mwana a ‘Nzeki: Nakuru First Bishop. https://youngcatholicpriest.blogspot.com/2020/03/archbishop-emeritus-ndingi-mwana-nzeki.html Accessed on 29/12/2023.

- The Catholic Mirror, 1 April, 2020.

- Throup, D (1995). Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, in H. Hansen and M.Twaddle (eds.) Religion and Politics in East Africa. London: James Currey, 143-176.

- Wambua, C (2023) Oral Interview, Kabaa.

This article, received in 2023, was written by Professor Dickson Nkonge Kagema, an Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Theology at Chuka University, Kenya. He is the Coordinator of Chuka University, Embu Campus and a Canon in the Anglican Church of Kenya. (From Prof. Kagema: “I thank my PhD students, Elizabeth Kathure and Moses Mwithalii who assisted in gathering the information that was used in the compilation of this article”.)