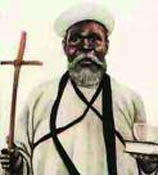

Harris, William Wadé (E)

William Wadé Harris, also known as the Black Elijah, Prophet Harris, or simply the Prophet, was a trailblazer and a new kind of religious personage on the African scene, the first independent African Christian prophet. [2]

Harris was born c. 1860 in the village of Half-Graway or Glogbale, in the Glebo Territory of Maryland County of the then-Commonwealth of Liberia. [3] He was born into an interfaith family. His mother, Youde Sie, was a Methodist and his father, Poede Wadé, a follower of the African Traditional Religion (ATR) of the Glebo ethnic group. As a child, Harris was introduced early into his father’s religion and culture.[4] When civil war threatened between the G’debo United Kingdom and the colonist settlers, in Maryland County in 1873, Harris’ maternal uncle and Methodist minister, the Reverend John C. Lowrie, took Harris and his elder brother away to Nimo Country of the Sinoe District where they were rigorously groomed and transformed at home, school, and church. They were taught to read and write in both English and G’debo, taught Christian faith doctrines, and grounded in the catechetical formations of Methodist life and practice. Harris also trained to become a stone mason. [5]

Upon returning to the Cape Palmas area, however, Poede Wadé withdrew Harris from this Christian setting and re-introduced him into Glebo ATR practice and culture, including the tradition of going to sea. Harris reported that he went to sea as a common laborer on four occasions. Upon his final return in 1882, Harris received a call to preach on the occasion of a sermon by the Reverend E. W. Thompson of the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) at Cape Palmas. Harris admitted that it was the first time he converted. Shortly thereafter, he was lured by brighter financial prospects at a neighboring Protestant Episcopal Church (PEC) under settler Bishop Samuel Ferguson (1885-1912). There Harris received the sacrament of confirmation and became a full member. Three years later (c.1885 to 1886) he married Rose Bedo Wlede Farr in a church solemnized matrimony.

As a young man, Harris sought new religious identities. First, he studied Russelite or Jehovah’s Witness tracts which emphasized millennialism and Christian eschatology. Second, Harris was attracted to the anti-colonialist position of his Glebo family member, the Reverend S. W. Seton. He was a Russelite ordained minister of the PEC, who became a politician, an education commissioner, and a judge. Seton founded an Independent African Church called The African Evangelical Church of Christ (AECC) which allowed polygamy. Third, Harris was interested in a West-Indian born Presbyterian minister, writer, and academic by the name of Rev. Dr. Edward Blyden. Blyden became a politician and a diplomat who advocated that African Christianity show respect for the polygamous family and felt that faith ought to be preached based on the model of Islam with African culture serving as a background.

Trained by the PEC to be a schoolmaster, a catechist, an evangelist, and an ecclesiastical “knight in armor,” Harris fought several battles for both tribe and church, including that of the decisive Battle of Cavalla (1893 to 1896). By the end of 1907, Harris was at the zenith of a golden period. He was, simultaneously, the master of the boarding school, a PEC appointed lay reader, a Glebo court interpreter, and the secretary of the Glebo peoples. He earned at least $400 per year. However, he was implicated in the 1908 national unrest, and by June 1908, he had lost his two lucrative jobs as schoolmaster and court interpreter. Immediately afterwards, his license as a lay reader was also revoked.

Fuming, Harris replaced a Liberian flag with a Union Jack flag on a flagpole at Puduke Beach on February 13, 1909, causing him to be accused of taking part in an abortive coup d’état. Harris was then arrested and tried for treason. Being found guilty, he received a two-year suspended sentence with fines. When civil war broke out again in the Cape Palmas area in January 1910 between the Nyomowe–Glebo and the American-Liberian settlers, Harris was re-arrested and imprisoned at Graton Prison. Here, in May and June of 1910, he had a supernatural spiritual experience in the form of an almost indescribable “trance-visitation.” It had a powerful effect on Harris. He broke-free, irrevocably, from Glebo ATR demon worship. A Christian interpretation of this “trance-visitation” is that Harris received the spiritual light of prevenient grace [6]; he was divinely operated upon and this gave him the experience of feeling right with God by receiving justifying grace [7]. He was anointed, commissioned, and tasked with the cooperative sanctifying grace [8] to spread the message of salvation in Jesus Christ through the preventive act of baptism.

On a Sunday July 27, 1913, three years after the “trance-visitation” experience, Harris embarked on his first evangelical missionary journey (1913-1915). Leaving Cape Palmas on foot, accompanied by two women chorus singers, Helen Valentine and Mary Pioka, he walked eastwards to the littoral lands of the Lagoons, through the Zana Kingdom up to the Ankobra River in Appolonia. At Assinie in the Zana Kingdom, former Tano priestess and converted Grace Tanie or Thannie joined the choral group. This mission had a powerful impact on the lives of some 200,000 people who converted. A new vibrant faith sprang up that created bonds of unity among people of different tribes and across colonial borders.

By August 1914, Harris and his expanded team retraced their steps to Côte d’Ivoire. At some point between January and April 1915, French colonial authorities resolved that as a precautionary measure they would arrest and deport Harris.[9] They quietly escorted him back to his native Liberia, nearly three hundred miles (approximately five hundred kilometers) away, traveling over land and on river. He was forbidden to return to French soil. Within seventeen months, from 1913 to 1915, hundreds of Christian communities sprang up. Groups of men and women seeking God earnestly asked for Christian instruction. His principal effect was among the Kwa group of peoples in West Africa. [10] This inaugurated Harris’ public international ministry (c. 1913 to 1921). Three other international missionary journeys followed (1916, 1917, and 1921). However, the first of these journeys will suffice to give insight into Harris’ unique message, praxis, heritage, and legacy.

Harris’ Message: Torahic, Analogical and Christo-Eschatological

Torahic

A torahic message refers to matters pertaining to the Hebrew Torah either directly to the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17) or indirectly to the six-hundred-plus Jewish Laws found within the Torah, or loosely to the whole Jewish Scriptures, a near-equivalent of the Christian Old Testament (OT). One Roman Catholic priest, the Reverend Fr. Joseph Gorju of Bingerville and missionary reporters Cooksey and McLeish have reported that Harris called for the abandonment of fetishes and idols (Exodus 20:3) and for belief in one unique God (Exodus 20:4).

Within Harris’ operational zone, recent research has unearthed some additional teachings. Mathieu Sedji, a 20th to 21st century history teacher and choirmaster from Breffedon, relayed by memory an oral pronouncement which Harris first proclaimed at Louzoua around August-October of 1913:

Brûlez les fétiches;

Chassez les démoniennes, les sorceries et les génies;

Allez à l’eglise les dimanches et ne partir pas aux champs!

(Burn the fetishes;

Drive out from your midst demons, sorceries and genies;

Go to church on Sundays and do not go to (your) farms!) [My Translation] [11]

In this torahic oral declaration, Harris urges the spiritual purification of the community and obedience to Sunday Sabbath-keeping for worship, learning Scriptures, hymns, songs, and prayers. Converts were to emulate and honor the Creator God who “blessed the Seventh Day (Sabbath) and made it holy” (Genesis 2:3).

Analogical

Harris’ message was also said to be analogous (άναλογος) or “analogical in faith” (analogia fidei) to that of 9th c. B.C. prophet Elijah. These claims were tested in two real-life encounters. Marc Nga was an eyewitness of the Harris campaign through the Yaou-Bonoua Forest of the Aboures in December 1913. Harris challenged the priests and priestesses of the twin shrines, of the Gbamanin du Yaou (The Dwarf of Yaou Forest) and Le Serpent à Bonoua qui vomit l’argent (The Serpent in Bonoua which vomits money). Nga reported that Harris defeated the priests and priestesses on their own home-turfs, convincing many that Harris’ God was greater. [12] Another eye-witness to these events was Jean Ekra de Bonoua, who with Marc Nga, were both baptized by Harris and became his disciples. Harris’ preaching in the forests was analogous (άναλογος) to the Prophet Elijah’s challenge posed to the 450 priests of Baal, the 400 priestesses of Asherah and the crowds: “How long will you waver between two opinions? If the LORD is God, follow him; but if Baal is God, follow him” (1 Kings 18:21). Harris also invited decision-making at the shrines. Just as God gave victory to Elijah, so he did to Harris over the priests and priestesses of the twin shrines (1 Kings 18:46).

Abaka Ernest Foli narrated a modern variant of an established Harris tradition concerning the burning of a ship at the port of Grand Bassam on a Sunday when people ignored his warnings. According to Abaka:

- Le deuxième miracle de Grand Bassam:

Un dimanche, les blancs travaillaient les noirs au bateau à (Grand) Bassam.

Il n’etait pas d’accord.

Il a prié sur le bateau,

Le bateau a brûlé.*

(The second miracle in Grand Bassam:

One Sunday, the whites recruited blacks to work a ship in (Grand) Bassam.

He (Harris) did not agree.

He prayed on the ship,

The ship caught fire). [My Translation] [13]

Disobedience led Harris to rain fire on the ship. In a case which was “analogical in faith” (analogia fidei). Prophet Elijah had ordered that fire to rain, twice, on the King Ahaziah’s attacking troops (1 Kings 1:9-12) following a reprimand from Elijah.

Christo-eschatological

This is some evidence that, from time to time, Harris did broadcast a Christo-eschatological message. In October and November of 1914, after Harris’ return from the Gold Coast, he settled at Kraffy, making it his headquarters. Thousands flocked to Kraffy from all directions, quietly, for fear of the colonial authorities. The traditional elders of Kraffy were stunned by Harris’ charisma and therefore enquired: “Are you the great spirit of whom they speak?” To which Harris pointedly responded in the negative, and then responded with clarity, “I am the man coming in the name of God, and I am going to baptize you in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and you will be a people of God.” [14] Harris repeated the universal baptismal formula (Matthew 28:18-20), where the “Son” refers to Christ himself.

A distinguished African Christian scholar, J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, has recently submitted that wherever Pentecostalism emerges the message of the parousia is preached. [15] Asamoah-Gyadu further substantiated that Harris “promised deliverance, from a future judgment of fire and a time of peace, concord, brotherhood and well-being which was to come with the impending return of Jesus Christ to establish his kingdom.” Several other Christo-eschatological messages have been reported during Harris’ travels which affirmed the supremacy of Christ and conveyed apocalyptic warnings against disobedience.

Harris’ Praxis: Evangelical, Situational–Dispensational, and Ecumenical-Participatory

Harris’ first evangelical missionary journey (1913-1915) enabled three distinct and contingent components of his praxis to be systematized: the evangelical, the situational-dispensational, and the ecumenical-participatory. Shank’s brilliant scenic narrative is an eye-opener to these habits.

They would enter a village playing their calabash rattles and singing, dressed in white, and would go to the chief of the village to explain their intent. Harris would then preach to the whole village, usually through an interpreter. He would invite them to abandon their “idols” and “fetishes”, and worship the one true God who had brought salvation through his Son Jesus Christ. To those who destroyed their “fetishes” and were baptized, he promised deliverance from future judgment of fire and a time of peace, concord, brotherhood and well-being which has to come with the impending return of Jesus Christ to establish his kingdom. He taught the Ten Commandments of the Old Testament and the “Our Father” which Christ taught his disciples. He instructed them about keeping the Sabbath for worship, not work, and encouraged them to pray in their own tongues, to praise God with their own music, changing the words. He often chose leaders, sometimes naming “twelve apostles”, who were to supervise the building of “chapels” from local materials. Sometimes they were told to await white men who would come with the Bible to teach them more. If there were missions in the area the people were told to go to those churches, whether Catholic or Protestant. [16]

Evangelical Praxis

Upon entering a village, the chief was greeted first. The team’s mode of greeting was evangelical (gospel-related) in that Jesus Christ enjoins us to this habit as clearly spelled out in the Matthean text: “Whatever town or village you enter, search for some worthy person there and stay at his house until you leave. As you enter the home, give it your greeting” (Matthew 10:11-12; NIV).

Harris’ team expressed Christo-African greetings which endeared them to their hosts. Together with female choristers and the locally recruited male interpreter(s), they accompanied his preaching with singing, dancing, and the playing of calabashes. Harris declared the kerygma (κηρυγμα) [17] in the mother-tongue of their hosts and never accepted any form of payment except for their hospitality. Harris always preceded his evangelism with moments of deliverance and healing. Local healers who became converted through Harris were taught to acknowledge Christ as the true source and giver of their medicinal, psychological, and pneumatological charismata (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:8). His evangelical style included en masse village repentance and baptisms, and evangelical conversions of priests and priestesses at their respective shrines. Harris’ evangelical praxis encouraged self-propagation. Many converts were allowed freedom to found new congregations or independent churches, as did Grace Tani of Assinie of Twelve Apostles Churches; and John Swatson of Aboisso of Christ Church Beyin churches.

Situational-Dispensational Praxis

Attire and marriage were situational-dispensational praxis items to Harris. The Harris team was always clad in white. White was, and is, the color of the cassock of Christian priests. White was, and is, the color of the Mahomedan or Islamic sheikh. White was, and is, also the color of the African Traditional Deyabo priest in Greboland. And white was, and is, the color of the Adjokuru priests and priestesses of the Tano shrine of the Lagoons.

Marriage is the second component of interest. Harris entered into a monogamous solemnized matrimony with Rose Bodede Farr at the Protestant Episcopal Church (1885) in Liberia. This union produced six children and was only separated by death in May-June of 1910.

During his first evangelical missionary journey, he was accompanied by female choristers. Rumor had it that Harris had several wives. In an interview in 1926, Harris admitted that at Axim, he had six wives. Harris supported his polygamous situation with Scripture (Isaiah 4:1). His polygamy began with Helen Valentine and Mary Pioka; next there was Madame Harris Grace Thannie; third, there were three more unidentified wives at Apollonia; and finally, there was Letitia Williams of Freetown whom he married in about 1921. Harris viewed polygamy as an imperfect marriage dispensation which attracts neither a binding legalism nor an illegalism in Christianity (cf. Romans 2:1). On his return journey to Grand Lahou Kpanda, Abaka Ernest Foli reported that Harris released a marriage maxim there: “Soyez juste, soyez equitable” (“Be just. Be fair”). [18] That is to say, with respect to either a monogamous or polygamous marriage, one should be guided by ethical righteousness.

Ecumenical-Participatory Praxis

One Sunday morning at Jacqueville in about December 1913, Harris attended Mass at a Roman Catholic Church. It was the Reverend Father Moly, the celebrant, who told his story:

I saw him at Jacqueville where he attended the parish mass with all his wives, accompanied by almost all the population. It is useless to say that the church was too small. Also at the end of the mass, he came to see me accompanied by the elders of the village, in order to decide to construct a more spacious church. [19].

Harris had acquired proven skills as a master-builder. He built his own single-story family house at Spring Hill Station in Liberia in c. 1890 [20] and the Wolfe Memorial Chapel at Half-Graway in 1897. At Jacqueville, Harris invited an ecumenical family of worshippers to build a center of worship. Members of the Harrist movement volunteered to help construct or to enlarge church buildings.

Citing a spiritual habit, Adolphe Yotio Ndrin reported that at Kraffy, Harris ordered the implementation of mother-tongue liturgy and hermeneutics. Harris exhorted the crowds: “Priez dans votre langue et chantez dans votre langue. Dieu va comprendre” (“Pray in your language and sing in your language. God will understand.”). [21] Harris reduced the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and some basic liturgy into the local dialect. The liturgy utilized indigenous tunes arranged to “castagnette” rhythm accompaniment and were made simple but “rich in prayer and interspersed with impromptu lyrics in their native tongue or in pidgin English (Creole/Krio/Aku) – the language in which they heard Harris preach and sing” [22] according to Cooksey and McLeish.

Educational practices were reported by Cooksey and McLeish. As the little bamboo “do-it-yourself” churches (abatons) sprang up in the villages, Harris taught the new converts to choose twelve “apostles” to serve as leaders and manage the church affairs and a thirteen preacher who would lead worship services. Having choristers and a formidable network of selected translator-interpreters / clerks, they spread Harris’ message each in their own way. Since most were illiterate anyway, Harris advised that, wherever possible, they should be enrolled in the few schools around being set up by the Traditional Western Mission Churches (TWMCs) and the colonial authorities. At Jacqueville in Alladian territory, around December 1913, Harris released a popular educational maxim which Abaka Ernest Foli recollected by heart:

Mettez vos enfants à l’ecole!.Ils viendront. Ils vous diront la vérité. (…)

Je vous dirai la vérité qui est dans la Bible pour que

l’homme blanc et l’homme noir mangent à une même assiette, égal à égal

(Send your children to school! They will come. They will tell you the truth. (….)

I tell you the truth which is contained in the Bible so that

the black man and the white man will eat in the same plate, as equals… ) [23]

Harris prepared the minds of his followers to welcome Christian missionaries, whatever their denominations, as teachers in their midst. Followers must learn to self-discover, and test the veracity of his claims in the Bible. Harris firmly believed that education would bring about equality between the white and black races.

Harris’ Heritage

Liturgy

At the Temple de Gethsemane de la Mission Biblique Harriste No.1 Côte d’Ivoire de Grand Lahou Kpanda (hereafter referred to as the Temple de Gethsemane), the service liturgy represented an ecumenical composite of a rich ecclesiastical traditions compiled by Harris. The liturgist demonstrated Episcopalian precision in catechetical rubrics and order while the preaching had a Wesleyan vibrancy. There was a single lesson and a biblical exposition followed immediately thereafter. The choir emphasized the lessons learned through informal punctuations during the preaching. Hymns and the anthem were sung from memory in the home dialect of Avikam and under disciplined choirmaster control. The Psalm (Canticle) was sung in French. During the offertory, the elders, the choir and the congregation, in that order, recessed and processed with Avikam songs of thanksgiving, accompanied with choreographed dances. At the Temple de Gethsemane, one observed that the Harris’ legacies of catechism, charismatic prayer, and singing habits have been retained.

At l’Eglise du Christ-Mission Harriste du Yaou (hereafter referred to as l’Eglise du Christ-Yaou), close to worship time, metal gongs were struck to call the faithful to worship. The choir, the congregation, and the “apostles” were all clad in white. The ladies wore white head gear as well. The prédicateur-chef (senior-preacher) and prédicateur-auxiliaire (assistant preacher) were each robed in a white kaftan-cassock with a low cross chain. Both were adorned with: “carlotte blanche, britelle noire et voile noire” (white turban, black stole and black cross bands). Their attire replicated that for which Harris was renowned. The service liturgy was rich in prayer, catechetical affirmations, and hymn–singing, with menu change, punctuated by the ringing of the hand bell. Traditional songs were rendered by the choir and congregation throughout the service. Song and dance was accompanied by the infectious rhythm of the castagnette. Here, the charismatic chorale tradition of Helen Valentine, Mary Pioka and Grace Tani is alive and flourishing!

Worship at both the Temple de Gethsemane and at l’Eglise du Christ-Yaou were relatively brief, ranging from thirty minutes to about an hour. Both services were orderly, but not identical in form. Worship at the Temple de Gethsemane was found to be evangelical in emphasis while that of l’Eglise du Christ-Yaou could be described as neo-Pentecostal/charismatic. Despite their contrasting worship expressions, both had an almost identical order of service. The order of service of l’Eglise du Christ- Yaou is available. [24] In this typical order of service, four prayer registrations were noted: benediction (1), intercessory (4), the Lord’s Prayer (5) and a closing prayer (11), in that order. There were also four types of songs: an opening (adoration) hymn (2), a sermon hymn (6), an anthem (9) and a recessional hymn (12). The reading of Scripture by the prédicateur (preacher) always preceded the sermon.

Unlike the regular liturgy of the two Harris churches mentioned above, the order of service within the three sister Twelve Apostles churches in Western Ghana varied significantly. Worship patterns differed from one church to the other. Generally, however, worship services were longer in the latter with between three to four hours being typical. The liturgy of Twelve Apostles Church-Upper Axim is available. [25] Notwithstanding the expressed variances, it is called a typical Inkabomsom (get-together) Service. This service has retained the habits of worship of its founder, Grace Tani, a Harris disciple. A number of points deserve attention. First, although three prayer registrations have been listed (1), (2) and (3), yet they tended to merge into each other. The opening prayer (3) never actually ends until the conclusion of the service. Second, the opening song (4) also continues up to the end of the service. Third, the healing session (5) occurs concurrently with the opening prayer (3) and opening song (4). An Inkabomsom is a spiritual journey which could last up to three hours or more.

Preaching

Preaching was always reduced to the language of the hearers, into Avikam in Grand Lahou Kpanda and into Aboure in Yaou. Preaching at these Harris churches was found to be Scripture-centered. The choir led the congregation in acknowledged parts of the message with groans and voiced responses.

In the Twelve Apostles churches, worship was shared between preachers and healers. The highpoint of Twelve Apostles liturgy is the healing session which is normally officiated by healers. Preaching, healing, and divination seem to happen simultaneously. The service stops only when the participants are exhausted. For both Harrist churches and Twelve Apostles churches, the common response to preaching is normally dramatized in acts of singing and dancing, recessing from and processing towards the sanctuary, and always in their home dialect. Each worshipper responds to preaching as he or she presents his or her physical gift offering at the sanctuary. The song or dance rises to a crescendo at presentation.

Deliverance and Healing

In his interaction with the men of Trefedji, one crucial point made about his exorcism is that Harris always led and directed the deliverance and healing process.

In most Twelve Apostles churches (“gardens”), deliverance and healing were the dominant activities of worship. However, as far as countering fetishism was concerned, the calabash was required at both spiritual and water healing. At the Twelve Apostles Church-Iyisakrom “garden,” the leading healer and prophetess Hagar Yarlley was questioned about the source of her medicinal power. She declared that with “the help of Jesus Christ and by prayer, I am a healer of barren women, of impotent men, of the paralyzed and of psychiatric patients.” [26] Prophetess Hagar Yarlley was trained by her grandmother, Prophetess Hagar Efuah Ntsimah (Antwi) of Upper Axim. The latter was ordained by Grace Tani in Ankobra on March 6, 1949. As she conducted healing, Hagar Yarlley continued saying that she received “visions which reveal, through the Spirit, the herbs which are to be selected in the treatment of my patients.” It will be recalled that Harris gave a similar response to the healers at Louzoua in October-November 1913.

At the Twelve Apostles Church–Half-Assini, the leader and healer in charge, Apostle Abraham Kaku, declared that he specialized in “psychiatric and mental cases, including the curing of drug addiction.” [27] Apostle Kaku, like Harris, attributes his healing power to Christ Jesus.

At the Harriste Biblique No.1 Côte d’Ivoire (HBCI) of Grand Lahou Kpanda, Adolphe Yotio Ndrin declared that the use of the big calabash at routine church services was forbidden. Adophe Yotio explained that the uses of “both the ‘big calabash’ and the ‘castagnette’ (small calabash gourd with net of beads) have no place at Temple de Gethsemane.” Exorcism, according to Adolphe Yotio, was a holy rite that should not be routinely abused. For him, in particular, the castagnette, invokes sad memories of a once demon-filled community which have since been cleansed by Harris and his assistants.

Symbolism

Four dominant liturgical symbols are associated with the Harris ministry: the Cup, the Bible, the Calabash and the Cane Cross. These symbols have assumed varying significance within the Harris churches studied.

At Twelve Apostles Church–Half-Assini, all four sacred symbols have pride of place. With regards to the Cup, Apostle Kaku asserted that as their prophet, he would gaze on the water. In so doing, he meditated and invoked mediation for the person or the assembly, as the case may be. The water in the Cup assumed a state of sanctification. The sanctified water was normally sprinkled on worshippers or consumed by select persons.

The second symbol of worship, the Bible, was normally held opened throughout worship and healing ministry. It is either read to the audience or tapped on the head of baptismal candidates. It is a revered source of power. The very utterance of the words of the Bible provided healing to the sick and to hearers.

The third liturgical symbol is the Calabash. Apostle Kaku says that he still uses the Calabash in the Harris tradition, which is mainly to exorcise evil spirits.

Fourthly, there is the imposing Cane Cross. This symbol has dual functions at Twelve Apostles Church–Half-Assini. While it may be gazed upon by believers for inspiration and strength, it could also be thrust upon agents of the devil or Satan in order to rebuke evil spirits.

Sacraments

Mission Biblique Harriste No.1 Côte d’Ivoire de Grand Lahou Kpanda recognizes three ordinances, not sacraments, in its published constitution. These are the sacred rites of baptism, Eucharist, and marriage whose rubrics are, respectively, quite similar to that of the Methodist Service Book of the Methodist Church Great Britain.

Relatively new and unique sacred rites of the Harrist Movement have been described elsewhere.

- Sacrament of Baptism: [28]

This is a dominical sacred rite. There were deficiencies with respect to the original Harris tradition where cleansing, penance and washing (by water and spirit) were emphasized. In the current rites, neither is exorcisms practiced, nor is repentance insisted upon.

- Sacrament of Agape Meal at Incarnation: [29]

The Incarnation or Christmas is recalled on the nominal birthday of Jesus Christ on December 25 at 2 pm. A grand meal is consumed using the Eucharistic rubrics (Matthew 26:26-28).

- Sacrament of Agape Meal on July 27th - la Fête du Déluge: [30]

The start of Harris’ first evangelical missionary journey (1913-1915) is commemorated at 2 pm. A grand meal is consumed using the Eucharistic rubrics (Matthew 26:26-28).

- Sacrament of Sacrifice: [31]

This service is held on Good-Friday only. This sacrament is meant to symbolize the significance of the passion, death, and living sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The Sacrament of Baptism, the Sacrament of Agape Meal at Incarnation, and the Sacrament of Sacrifice are viewed as dominical sacred rites by the Harris movement. That of the Sacrament of Agape Meal at the Fête du Déluge is an ecclesiastical feast dedicated to the works of the founder.

Harris’ Legacy

In the Methodist Church

Just over a century ago, hundreds of Harris communities were founded within Harris’ operational zone. It has been documented that some of the Harris communities in the Yaou-Bonoua forests became part of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. One of these is the distinguished Temple de St. Espirit de Bonoua of l’Eglise Méthodiste Unie Côte d’Ivoire (EMUCI) (Methodist Church of Côte d’Ivoire) which was rebuilt into a huge cathedral, almost of basilica proportions, and consecrated in 2005. Written high on the front wall of the sanctuary, embossed in bold red letters, is an apocalyptic message: “Je Regardai, et Voici, Une Porte Etait Ouverte Dans le Ciel’ (Apoc. 4:1) (“I looked, and lo, in heaven an open door” –Revelation 4:1, RSV) [123]. This text-sign falls within the typical Christo-eschatological genre of Harris’ message. The text sign represents the echo of a dominant Harris preaching. [32]

In Catholic Churches and other Protestant Churches

Harris’ legacy was measured through his impact on numerical membership of Christians and the influence of his mother-tongue initiatives. From 1893 on, the residing French Protestant Governor Louis Gustav Binger of the colony of Côte d’Ivoire sent special invitations to many Christian missions, with assurances of financial support and collaboration to establish schools, clinics and churches within at least six identified growth centers: (Grand) Bassam, Moossou, Dabou, Memni, Bonoua, and Assinie and later extended to Jacqueville (1898), Bingerville (1904), Abidjan (1905), and Abiosso (1905). [33] E. Amos Djoro observes that just before the start of World War I (1914 to 1918) the Roman Catholic Mission then had 23 missionaries, and had registered barely 1,100 full members and 400 catechumens in the whole of Côte d’Ivoire. [34] However, the writer noted that by 1917, the population of Roman Catholic catechumens had increased to 800; and five years later in 1922, catechumens had risen, exponentially, to almost 20,000. [35] In Apollonia, in the Western Gold Coast, it was equally dramatic: “There were only already in 1920, 3,240 members and 15,400 catechumens where there had been no baptized Catholics in 1914.” It will be recalled that Harris launched his first evangelical missionary journey in 1913-1915 through the same areas where the centers of evangelization had been established in Côte d’Ivoire and in Apollonia. Only one rational reason could explain these spiked numerical increases in membership over the 1914 to 1922 period – a definite attribute to Harris’ legacy.

Since the end of Harris’ first evangelical missionary journey (1913-15), the smaller TWMCs at the time have now become the greater and the Harris communities that were greater are now the smaller. In Côte d’Ivoire alone, 11.6% (0.2 million) of the population was registered within the Harris movement out of a total population estimate of 1.6 million in 1926. [36] By the year 2001, however, there were major reversals. The Harris movement accounted for barely 1.6% (0.2 million) of the 11.4 million classified Ivoirians. [37] Besides bearing the brunt of injustice, the internecine and extended litigations since the 1930s, between the leaderships of Mission Biblique Harriste No.1 Côte d’Ivoire headquartered at Grand Lahou Kpanda and those of l’Eglise du Christ- Mission Harriste whose seat is at Bingerville, have further complicated the situation and undermined growth of the Harris Movement. It would seem that the leaders of Harris churches need to regain the ecumenical and reconciling spirit of their founder.

In a second thesis legacy, one asks: How did Harris’ initiatives in mother-tongue liturgy and hermeneutics penetrate Roman Catholic and other TWMCs? It was standard practice that up to the early 1960s, worship services in Roman Catholic churches, globally, were held strictly according to the rites and rubrics of the Latin Gregorian Mass. This was also the case of the Catholic churches of the Lagoons, the Zana Kingdom and Apollonia. When the Catholic Church convened in Rome the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), this was its 21st International Ecumenical Council which belatedly addressed relationships between the Roman Catholic Church and the modern world. Among its several reconciliation resolutions was a crucial decision to encourage the “widespread use of the vernacular in the Mass instead of Latin.” [38] It will be recalled that Harris, at his evangelical capital of Kraffy, had exhorted his audiences to pray in their own languages. Kraffy is located in the Lagoons. The Harris mother-tongue liturgy and hermeneutics influence had already penetrated the Roman Catholic Churches and other TWMCs well before the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) publicly and officially acknowledged it as most appropriate mode of propagating the Gospel.

Conclusion

Harris’ message and praxis have been implanted, incubated, fertilized, and cross-fertilized through the hundreds of house churches or abatons, which were founded and which eventually metamorphosed into Harrist churches, Twelve Apostles Churches, Christ Church Beyin, and many others. In addition, the catechumens sent to the Traditional Western Mission Churches (TWMCs) introduced African songs, shouts, dances, and pneumatological experientialism into an otherwise rigid TWMC life and liturgy. The Harris heritage remains strong within the ambit of the Kwa group of peoples distributed in Côte d’Ivoire, the Gold Coast (Ghana), Liberia, Sierra Leone, and beyond. Indirectly, Harris’ legacy in its fluid African worship patterns is global. The worship expressions of several charismatic and Pentecostal churches betray traces of the Harris style. Harris’ message and praxis have permeated large swaths of Christianity.

Some Harris churches of Côte d’Ivoire recognize July 27 as the Feast of the Flood (Fête du Déluge) to mark the beginning of that epic first evangelical missionary journey (1913-15). Besides the few women chorus singers and the interpreters/ translators who actively participated in his ministry, William Wadé Harris received little or nothing from churches, governments, societies or bankers. Harris pursued a missio dei which bore abundant fruit of eternal life in Christ Jesus. He planted Christian communities where previous governments, armies and churches had failed. Perhaps someday, the Christian calendar will reflect this amazing grace of God wrought through a man of God called the Black Elijah, Prophet Harris, Apostle Harris, and Saint Harris!

Gabriel Leonard Allen

Notes:

-

This biography is an abridged and adapted version of the author’s B.D. Honors dissertation: Allen, Gabriel Leonard. “William Wade Harris (c. 1860-1929): A Life, Message, Praxis and Heritage.” B.D. diss., Trinity Theological Seminary, 2008.

-

Bediako, Kwame. Christianity in Africa: The Renewal of Non-Western Religion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995.

-

There is now scholarly consensus on Harris’ date and place of birth. See Notes 5 and 6 in David A. Shank, abridged by Jocelyn Murray, Prophet Harris, The ‘Black Elijah’ of West Africa, (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 29.

-

Using David A. Shank’s work, Prophet Harris, The “Black Elijah” of West Africa (1994) as a primary guide, J. J. Cooksey and Alexander McLeish report on Religion and Civilization in West Africa: A Missionary Survey of French, Spanish and Portuguese West Africa and Liberia (1931) as historical reference, and the author’s field research in 2007-2008 which resulted in the work titled, William Wade Harris (c. 1860-1929): A Life, Message, Praxis and Heritage (2008); a tabulated chronological biography of Harris has been reconstructed.

-

His life can be divided into nine phases. These nine phases are:

Phase 1: Indoctrination in African Traditional Religion (c.1860-1873)

Phase 2: Methodist Catechetical Formation (1873-1879)

Phase 3: Personal Social Conflict (1879-1882)

Phase 4: Methodist Local Preacher (1882-1885)

Phase 5: Religious Search (ATR/ Islam/ Christianity) (1885-1892)

Phase 6: Episcopalian Formation and Conflict (1892-1898)

Phase 7: The Golden Period (1898-1908)

Phase 8: Indigenous Activism (1908-1910)

Phase 9: Public International Ministry (1913-1929)

-

“Salvation begins with what is usually termed (and very properly) Preventing Grace (Prevenient Grace); including the first wish to please God, the first dawn of light concerning his will, and the first slight transient conviction of having sinned against him… the beginning of deliverance from a blind unfeeling heart, quite insensible of God and the things of God. … Afterwards we experience the proper Christian salvation; whereby, through grace, we are saved through faith.” John Wesley, “Sermons” Vol. 5, 106-7, cited in “Wesley’s Order of Salvation” by Barrie Tabraham, Exploring Methodism: The Making of Methodism (Peterborough: Epworth Press, 2000), 32.

-

“By Justification (i.e. Justifying Grace) we are saved from the guilt of sin, and restored to the favour of God;…” J. Wesley, “Sermons” Vol. 5, 106-7, cited in “Wesley’s Order of Salvation” by Barrie Tabraham, Exploring Methodism: The Making of Methodism (Peterborough: Epworth Press, 2000), 32.

-

“By Sanctification (i. e. Sanctifying Grace) we are saved from the power and root of sin, and restored to the image of God…” J. Wesley, “Sermons” Vol. 5, 106-7, cited in “Wesley’s Order of Salvation” by Barrie Tabraham, Exploring Methodism: The Making of Methodism (Peterborough: Epworth Press, 2000), 32.

-

Shank reported that Harris’ deportation was decided by January 15, 1915, while Cooksey and McLeish believe that it was later, about April 1915.

-

The Kwa comprises the Kru dialects of Sierra Leone, Liberia & La Cote d’Ivoire; the Lagoon Languages of La Cote d’Ivoire; and the Akan languages of the Western Gold Coast. Cooksey and McLeish, 244.

-

Mathieu Sedji, interview with author, Temple de Gethsemane, Mission Biblique Harriste No. 1 Cote D’Ivoire, Grand Lahou Kpanda, June 17th, 2007, cited in Gabriel Leonard Allen, “William Wade Harris [c. 1860-1929]: A Life, Message, Praxis and Heritage” (B.D. diss., Trinity Theological Seminary, 2008), 35.

-

Abaka Ernest Foli, interview with author, Yaou Manse of Eglise du Christ Mission Harris (ECMH), Grand Bassam, June 11th - 13th, 2007, cited in Allen, 31, & Appendix ii, 5 of 6.

-

Abaka Ernest Foli, interview with author, Allen, June 11th to 13th, 2007, 32, & Appendix X, 7 of 21

-

Shank, 8.

-

Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, African Charismatics: Current Developments within Independent Indigenous Pentecostalism in Ghana (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005), 19.

-

Shank, 5-6.

-

Literally, the kerygma (κηρυγμα) is a Greek word which means “proclamation or announcement by a herald” Noting that a herald is a dependable and truthful person who normally reports with utmost fidelity what has been received from a higher authority. Biblically, the kerygma (κηρυγμα) is frequently associated with the spirit of the Pauline text conveyed in Romans of “I am not ashamed of the gospel, because it is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes … a righteousness that is by faith from first to last” (Romans 1:16-17; NIV); The kerygma (κηρυγμα) has also been interpreted theologically by many: A European Harris contemporary of the Neo-Orthodoxy era, restricted the kerygma (κηρυγμα) to “the public proclamation of Christianity to the non-Christian world” C. H. Dodd, The Apostolic Preaching and its Development (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1936), 7; One conservative Bible scholar, making particular reference to Apostolic preaching in the NT era, described the kerygma (κηρυγμα) as “a proclamation of (Jesus’) death, resurrection and exaltation…” R. H. Mounce,* The Essential Nature of New Testament Preaching* (Rapids: Eerdmans, 1960), 84; While the modern 20th century Christian theologian calls it “…the essential message or proclamation of the New Testament concerning the significance of Jesus Christ” see Alister E. McGrath, Christian Theology an Introduction (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 572. Paul Johnson,* A History of Christianity* (New York: Atheneum, …), 1.

-

Abaka Ernest Foli, cited in Allen, 43 & Appendix ii, 3 of 6.

-

Reverend Fr. Moly, cited by Shank, 8.

-

Shank, 62

-

Adolphe Yotio Ndrin , interview with author, Temple de Gethsemane, Mission Biblique Harriste No. 1 Cote D’Ivoire, Grand Lahou Kpanda, June 17th, 2007, cited in Gabriel Leonard Allen, “William Wade Harris [c. 1860-1929]: A Life, Message, Praxis and Heritage” (B.D. diss., Trinity Theological Seminary, 2008), 44.

-

Cooksey & McLeish, 61.

-

Abaka Ernest Foli, cited by Allen, 45.

-

The order of service of l’Eglise du Christ-Mission Harrist of Yaou:

BENEDICTION (The Most Senior Preacher rings the Bell to commence the service) OPENING PRAYER

An Invocation:

Eternal,

We give you grace and say thank you for this moment that you allow.

You have said in your word that where two or three meet in your name,

You are in their midst.

Come and guide this moment in the name of Jesus Christ.

OPENING HYMN PRAYER OF INTERCESSION (All on their knees. Ends with an Amen Song) THE LORD’S PRAYER SERMON HYMN THE GOSPEL THE SERMON (Preaching interspersed with shouts) AN ANTHEM - by the Choir ANNOUNCEMENTS BY AN ELDER (Collection on Sundays only) CLOSING PRAYER RECESSIONAL HYMN

Source: Liturgy: Ordinary Service at L’Egilse du Christ – Mission Harriste du Yaou, District of Grand Bassam, cited in Allen, 52 & Appendix iii.

- The liturgy of Twelve Apostles Church-Upper Axim:

1.0 CALL TO WORSHIP

An Invocation:

We begin this service in the name of the Father, the Son and the holy Spirit.

2.0 THE LORD’S PRAYER

3.0 OPENING PRAYER – by a Prophet or Prophetess

4.0 OPENING SONG –singing, praying and dancing

Kru Songs/ Hausa Songs/ Akan songs with Calabash accompaniment

5.0 HEALING SESSION –held in a special Room for Counselling

(Clients bring : packet of candles; 1 yard calico; 1 gallon water; Incense)

Water Divination - viewing 15-20 gallon water drums

Spirit Descends

Invitation for Consultation

Each worshipper arrives with containers of water

Raise the water up and told the future

Drink some of the water

Spiritual Messages received

Sick persons healed

Options: A Goat or Sheep is sacrificed

Source: Liturgy: Ordinary Service at Twelve Apostles Church –Upper Axim, Western Ghana, cited in Allen, 53-54.

-

Prophetess Hagar Yarlley, interview with author, Twelve Apostles Church - Ayisokrom, Western Region of Ghana, October 21st, 2007, cited in Allen, 54 & Appendix vii, 1 of 1.

-

Apostle Abraham Kaku, interview with author, Twelve Apostles Church – Half-Assini, Western Region of Ghana, October 23rd, 2007, cited in Allen, 52.

- Sacrament of Baptism:

-

An Elder of the church must be told about the intention.

-

The Elder shall inform either the Prédicateur Suprême (Supreme Head of the Harrist Church), the Prédicateur Supérieur (Superintendent Preacher of District equivalent) , the Prédicateur Chef (Senior Preacher of the Church equivalent), a Prédicateur (Preacher of the Church equivalent) or a Prédicateur Auxiliaire (Assistant Preacher of the Church equivalent).

-

The Baptismal ceremony could take place before, or after, any worship service.

-

The parent or guardian bearing the child to be baptized in his/her arms, or the individual to be baptized, approaches the Preacher and kneels down.

-

If the preacher is either the Prédicateur Suprême or the Prédicateur Supérieur, the individual concerned holds his cross of cane.

-

If the preacher is either the Prédicateur Chef or the Prédicateur or the Prédicateur Auxiliaire, the individual concerned holds his kaftan.

- The Preacher, with the Bible in the one hand and the cup of water in the other, responds with a Baptismal Prayer

*Dieu, Nous te demandons de laver ton serviteur

comme ton fils Jésus a été baptisé par Jean Baptiste dans le Jourdain.

Que ton esprit saint demeure en lui et chasse tout ce qui ne l’honore pas en lui

afin qu’ il soit véritablement ton fils/ fille. *

(Gracious God. We are asking you to wash your servant

as your Son Jesus had been baptized by John the Baptist in the Jordan.

May your Holy Spirit dwell in him /her and drive away all which does not honor you

Until he truly becomes your son/ daughter) (My Translation)

-

The Preacher pours water on the head of the baptized, three times.

-

The Preacher traces the sign of the cross with his finger on the forehead of the baptized.

-

The Preacher taps the Bible, three times, on the head of the Baptized

-

The Choir rounds up with a hymn.

-

The Preacher empties the rest of the water in the cup on the ground, reverently, during one continuous pour.

Source: Liturgie du Baptême (Liturgy of Baptism), cited in Allen, Appendix iv, 1 of 1

-

Sacrament of Agape Meal at the Incarnation, cited in Allen, 56.

-

Sacrament of Agape Meal at the Fete du Deluge, cited in Allen, 56.

-

Sacrament of Sacrifice, cited by Allen, 57-58.

-

Allen, 48-49.

-

E. Amos Djoro,Harris et la Chrétienté en Côte D’Ivoire (Abidjan: Société d’Imprimerie Ivoirienne pour le compte Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines, 1989), 27-30.

-

Djoro, 46.

-

Djoro, 46.

-

Cooksey & McLeish, 241.

-

In data released in 2001 on all who were resident in Côte d’Ivoire, the religious demography was:

- Catholic (20.7%);

-

Protestant (8.2%);

-

Harriste (1.6%)

-

Other Christian (3.4%)

-

Total Christian (33.9%);

-

Muslim (27.4%);

-

Animist (15.3%);

-

Other Religions (2.0%);

-

Atheists (20.7%) and

-

(Not Declared) (0.7%).

Source: Esso Badou, “RGPH 98, Tome 1: Etat et Structure de la population, INS. 2001: Table 3.5: Répartition (en pourcentage) de la population résidente par région administrative selon la nationalité,” in Joachim Kigbafory-Silue, Côte d’Ivoire, Nation Chrysalide (Abidjan: PUCI, 2005), 157.

- Second Vatican Council, https://en. Wikipedia.org/wiki/second_vatican_council.

Select Bibliography:

• Allen, Gabriel Leonard. “William Wade Harris [c. 1860-1929]: A Life, Message, Praxis and Heritage.” B.D. diss., Trinity Theological Seminary, 2008.

• Asamoah-Gyadu, J. Kwabena. African Charismatics: Current Developments within Independent Indigenous Pentecostalism in Ghana. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005.

• Bediako, Kwame.Christianity in Africa: The Renewal of Non-Western Religion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995.

• Cooksey J. J., and Alexander McLeish.Religion and Civilization in West Africa: A Missionary Survey of French, Spanish and Portuguese West Africa and Liberia. London: World Dominion Press, 1931.

• Djoro, E. Amos. Harris et la Chrétienté en Côte D’Ivoire. Abidjan: Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines C.I., 1989.

• McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

• Methodist Church Great Britain. The Methodist Service Book. London: Methodist Publishing House, 1975.

• Mission Biblique Harriste No.1 Côte D’Ivoire. MBH1CI Association Cultuelle: Statuts et Règlement Intérieur. Abidjan: MBH1CI, 2005.

• Omenyo, Cephas N. Pentecost Outside Pentecostalism: A Study of the Development of Charismatic Renewal in the Mainline Churches of Ghana. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum Publishing House, 2006.

• Parrinder, Geoffery. West African Religion: A Study of the Beliefs and Practices of Akan, Ewe, Yoruba, Ibo and Kindred Peoples. London: Epworth Press, 1978.

• Sanneh, Lamin. West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1983.

• Schaff, Philip.History of the Christian Church: Christianus sum: Christiani nihil alienum puto. Vol. III Part 2: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity: From Constantine the Great to Gregory the Great AD311-600. Grand Rapids: WM B Eerdmans Pub. Cp., 1953.

• Schlosser, Katesa. “Propheten in Africa.” Cited in Christian G. Baeta, Prophetism in Ghana: A Study of Some ‘Spiritual Churches.’ Achimota: African Christian Press, 1962.

• Shank, David A., abridged by Jocelyn Murray. Prophet Harris, the ‘Black Elijah’ of West Africa. Leiden: Brill, 1994.

• Smith, Edwin W. S. “The Christian Mission in Africa.” London and New York: International Missionary Council, 1926, 42

• Wesley, J. “Sermons.” Vol. 5, 106-7. Cited in Exploring Methodism: The Making of Methodism. Barrie Tabraham, 32. Peterborough: Epworth Press, 2000.

• World Council of Churches. Baptism Eucharist and Ministry (BEM) Document. Faith and Order Paper No. 111. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982.

This article, received in 2016, was written by Gabriel Leonard Allen of the Gambia, a theologian, an ecumenist, and an interfaith activist working in the Methodist Church and a member of the DACB Advisory Council.

This article also appeared in the October 2016 issue of the Journal of African Christian Biography. Click here to read the Journal.