Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Rainisoalambo (B)

During the thirty-plus years of persecution (1828-1861) under the reign of Queen Ranavalona I, Madagascar had edifying Christian martyrs like Marie Rafaravavy. In the waning years of the same century, during the beginning of the French colonization, Madagascar also enjoyed a religious revival that became, sixty years later, a Protestant Church that enjoyed legal status. There was actually nothing truly unique about that particular spiritual movement, because several other such movements were happening in Europe during the same period of time. However, it had its own characteristics because it began in the rural pagan milieu of the Betsileo region. The person who started it was named Rainisoalambo.

In those days, the quality of life in the island’s remote country areas was quite low. Death from consumption or smallpox was quite common. Bara and Sakalava raiders often swept down on poor villages in the Betsileo, and the kingdom made many taxing demands.

Rainisoalambo’s father was a Betsileo “marambasia,” a representative and a royal herald, and a good speaker. An intelligent pagan, he knew how to do divination using grain, he knew how to write horoscopes, and he knew how to use medicinal plants. He had taught all these arts to his son, who learned to use the efficient spells and the local medicinal formulas. This son of his was also charged with the care of a child named Vola, (who was actually a local lord), hence his original name, Rezaimbola, which meant “younger than Vola,” even though he was actually older. It was only when Rezaimbola’s own son was born that he took the name Rainisoalambo.

Unfortunately, spells and pharmacopoeia were powerless when it came to curing poverty, filth, ignorance, and malnutrition. After having witnessed the decimation of his family and his herd, and finding that he was unable to work because his body was covered with ulcers, Rainisoalambo called out to God from the depths of his misery, the God that the Norwegian missionaries had been talking about. These missionaries had arrived in 1866, and had been in Soatanana since 1877. That very same night, according to his own account, he heard the following order: “Throw away your amulets and means of divination. Throw them far from you.” He obeyed the order at dawn, and threw out the baskets of pieces of wood, the grains and the pearls, and every such thing he had accumulated. On that day, October 15, 1894, he felt that he had been delivered of his troubles and felt that his strength was returning. He knew that he had become a new man.

Since he already knew how to read, he began to devour the Bible, especially the New Testament. He was struck by the message he was getting from it, and told everyone in his entourage about his discoveries, encouraging them to get rid of their gris-gris (ody) so that they could recover their health. He was relentless in converting his family and his friends, and he was always talking with them about the promises and the affirmations he found in the Scriptures.

On June 9, 1895, twelve people who had been greatly helped by his advice held a meeting at his home. They all agreed that it was God himself who had restored their health, and that they needed to recognize God as such, and serve him. Each person went so far as to take some formal vows: that they would learn to read and to understand numbers so that they could read the Bible according to its chapters and verses; that they would clean their houses and courtyards, and have cooking fires in separate kitchens; that they would have vegetable gardens and have their own food resources; that they would begin everything with prayer, in the name of Jesus; that burials (which were ruinous occasions of drunkenness and debauchery among pagans) would be carried out in decent clothes, and that there would be songs, prayers, and exhortations, and that no cattle would be slaughtered for the occasion. This intimate and extraordinary meeting ended with an effusion of the Holy Spirit, which is how the “Disciples of the Lord” were born.

Rainisoalambo’s mission had been confirmed, so he immediately began to instruct the group using brochures like M. Borgen’s translation of Martin Luther’s “Short Catechism” that he was able to get from a missionary named Theodor Olsen. In October of 1895, the entire group came to Olsen and asked him to baptize them.

Rainisoalambo’s village, Ambatoreny, quickly became a place where sick people gathered. The newly converted would exhort the sick, raise their voices in prayer for them, and lay hands on them. Also, many of the “disciples” rushed out to tell their neighbors or their families about what had happened to them, and exhorted them all to do as they had done. Rainisoalambo gave some of them supplementary teaching (which they received from him while they were still full-time farmers), and sent them out two by two, designating them as “apostles” with the following watchwords: repentance, humility, patience, love of one’s neighbor, prayer, communion, and mutual assistance.

France’s annexation of Madagascar had given rise to a certain entrepreneurial vigor and a somewhat intolerant attitude towards Catholicism, so the beginnings of the movement went almost unnoticed. Its activities were modest, and it tried not to attract the unwanted attention of the new authorities. It was only in 1899 that the Awakening (Fifohazana) began to spread. Seeking a calmer environment, Rainisoalambo left Ambatoreny and settled in Soatanana, close to the Norwegian Lutheran Mission.

He kept his message simple and adapted it to the people that could be approached by these humble apostles. The adapted message could be summarized thus: trust in God, read the Bible, reject the gris-gris and pagan practices, practice agriculture, cultivate gardens, plant trees, abstain from alcohol and tobacco, and practice monogamy. In addition, and with great authority and conviction, the “apostles” also practiced the “laying on of hands” to heal the sick, and chased out demons in Christ’s name. Exorcism and healing became inseparable from the preaching of the gospel.

Wherever the apostles were received favorably, and wherever a small group of people accepted their message, they would name one of the faithful as a “guardian” who would then lead and exhort his brethren.

Rainisoalambo was constantly training new disciples and sending out new apostles every year. They were all recruited from the countryside, and they would return to their milieu after they had received the teaching. In 1904, the old “mother-and-father,” [as he was called], planned to have a grand reunion in Soatanana, which was set for August 10. He invited all those who had accepted the gospel message as he had set it out for them, and who were living in conformity with the very simple rules of the small community. He had commissioned the construction of a very large house in order to welcome the numerous guests he was expecting, and had provided for a large amount of rice to feed them all. The meeting took place without him however, because he had become old and weak, and he died on June 30.

Rainisoalambo, of blessed memory, is held in high esteem among all the Protestant churches of Madagascar to this day.

Louis Molet

This article, which is reprinted here by permission, is from Hommes et Destins: Dictionnaire biographique d’Outre-Mer [People and Destinies: Overseas Biographical Dictionary] vol. 3, published in 1977 by the Académie des Sciences d’Outre-Mer (15, rue la Pérouse, 75116 Paris, France). All rights reserved.

Photo Gallery

[1] Three leaders of the revival in Soatanàna. From left to right : Rajeremia and his wife, Rainitiaray and his wife, Rainisoalambo and his wife. The Bible is on the table between them. They are wearing a lamba (a type of shawl).

[2] The Mission in Soatanàna, 1892-1895. Photograph: Théodor Olsen.

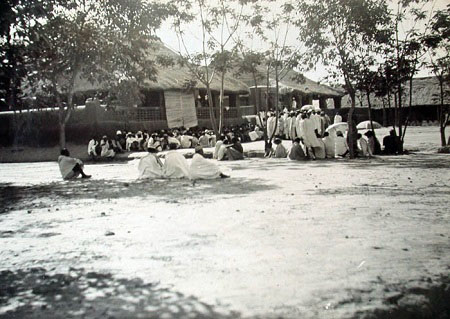

[3] Outdoor meeting in Soatanàna, around 1906.

[4] Group of people outside in the courtyard for a meeting. Betsileo.

[5] Preparations being made for a revival meeting, around 1906. Preparations often took all day.

[6] Revival meeting in Soatanàna, about 1906. Some are seated under parasols.

[7] Landscape around Soatanàna.

All photographs are printed with the permission of the Mission Archives, School for Mission and Theology, Stavanger, Norway.