Hetherwick, Elizabeth

Elizabeth Pithie was born in Aberdeen on 18 March 1861, the first and only child of James Pithie and his wife Isabella. Tragedy struck as her father drowned when he fell off the quay into Aberdeen Harbour when Elizabeth was only two weeks old. This left her mother to bring her up as a single parent in conditions of considerable poverty. The situation became even worse when Elizabeth was eleven and her mother died of consumption. Her education at North Lodge Industrial School was subsequently funded by a charitable group in Aberdeen. Its members were aware of the recently founded Blantyre Mission in Malawi and its desperate need for staff. They offered to pay Elizabeth’s salary if she were appointed to serve as a teacher. The policy of the Church of Scotland Foreign Mission Committee as regards appointment of women missionaries was that they should be of mature age and from well-off families. Elizabeth was neither but was appointed nonetheless, apparently on account of the desperation of the Committee to address the shortage of staff at the Mission. [1]

Hence Elizabeth arrived at Blantyre as an eighteen-year-old in 1879, the first unmarried woman to join the staff. As well as adjusting to an entirely new context and culture while suffering bouts of malaria, she had to contend with a male-dominated ethos within the Mission and a leader, Duff Macdonald, who refused to allow her to do any teaching in the school. She was given more menial tasks such as running the student hostel. She made her home with William and Bella Milne, a couple who had been her companions on the journey from Scotland to Blantyre. This source of support was lost when Milne fell out with Macdonald and left the Mission. It was in this context that she met and married another member of the Mission staff, George Fenwick. He had been one of the first appointments to Blantyre Mission but proved to be a most unsuitable missionary as he became notorious for bad temper, drunkenness and violence. Along with others, he was dismissed from the service of the Mission in 1881 as the Church of Scotland attempted to deal with a scandal that engulfed it when its missionary staff at Blantyre went to extremes in the imposition of violent punishments on alleged offenders. [2]

Soon afterwards Fenwick was recruited by the African Lakes Company, a commercial enterprise closely associated with the Scottish Missions, to which he could offer his skills as an elephant hunter and trader. He and Elizabeth moved the short distance to the ALC compound in Blantyre where their two children Jose Nunes and George were born. Elizabeth was often alone with the children as Fenwick was away on hunting expeditions. After a furious row with John Moir, the manager of the ALC, he was dismissed by the company and set up as an independent trader. Tragedy struck the family as Jose died on 22 October 1883 and George suffered the same fate just two months later. Elizabeth herself became seriously ill at this time. Early the following year, after a drunken argument, Fenwick murdered the Makololo chief Chipatula with whom he had been trading. He fled to an island on the River Shire pursued by Chipatula’s men who killed him when his ammunition ran out. This left Elizabeth in a precarious position since the senior Makololo chief Ramakukan demanded that she be handed over to him along with all of Fenwick’s property by way of recompense.

At this moment of crisis, the new Head of Blantyre Mission, David Clement Scott, and his wife Bella invited Elizabeth to live with them, which she did for the next four years. Having been orphaned as a child and then having lost all her family to death as a young adult, the stability and hospitality of the Scott household in the mid-1880s meant a lot to her. Indeed, the years that Elizabeth spent as a member of the Scott household proved to be a turning point for her, described by John McCracken as “the fulcrum for her later achievements.” [3] By the late 1880s she had become a well-respected member of the Mission community, fluent in Chinyanja and a capable teacher who enjoyed good rapport with the African community. When she went on leave to Scotland in 1888, Clement Scott remarked: “Mrs Fenwick leaves for home … she has been working now almost nine years and the people are greatly attached to her. Her knowledge of the language, her sympathy with the people and her gentleness of disposition have made them regard her as belonging to them, and her going seems almost the losing of one of themselves.” [4] Though it was not until May 1892 that she was included again on the mission payroll, by then she had long been established as an effective member of staff.

During her years as a member of the Scott household she met often with Alexander Hetherwick who joined the Mission in 1883 and soon established himself as Scott’s right-hand man. The two had first met in sad circumstances when Hetherwick, soon after his arrival in Blantyre, conducted the funeral of Elizabeth’s infant son Jose. When they were both due for home leave in 1888, they sailed to Scotland and back on the same ship, the many days at sea providing an opportunity for them to deepen their friendship. A slow-burning romance ensued over the next few years as Elizabeth took every opportunity to visit Domasi Mission where Hetherwick was based. Their marriage on 22 June 1893 was a momentous event in the history of the Mission. Two Malawian couples were married on the same day and the three couples held a shared reception, a powerful demonstration of the non-racial Christian community that Scott and Hetherwick were seeking to foster and to which Elizabeth gave her wholehearted support. Some schoolgirls walked the 50 miles from Domasi to attend the wedding celebration. [5] Two children were born to the couple: their son Clement, named after their colleague and leader, in 1895 and their daughter May in 1903.

When Hetherwick wrote his history of Blantyre Mission, he made no mention of his wife despite the fact that she was, for many years, the longest-serving member of staff and the only one who could remember the turbulent early years of the 1870s. [6] In a patriarchal culture it was not unusual for the contribution of women to be overlooked. However, Elizabeth did enjoy a rare moment of recognition when she completed twenty years in the service of the Mission in 1899. She was presented with a silver rose bowl and the Mission newspaper Life and Work commented that, “She only of the present staff has seen the Blantyre of the past, shared its excitements, troubles and successes.” [7] The following year, when the Livingstonia missionary Angus Elmslie was making preparations for the Missionary Conference to be held at Livingstonia, he was keen that Elizabeth should be one of the speakers, telling Hetherwick, “We look to her as the most experienced lady worker in the country.” [8] By this time Hetherwick had succeeded Scott as Head of the Mission and for twelve years Elizabeth presided at the Blantyre Manse, dispensing what W.P. Livingstone, one of their many visitors, described as “a generous, warm-hearted hospitality which has seldom been equalled in Africa.” [9]

By the time she left Blantyre for the last time in 1910, she had completed 31 years of missionary service. For the next 18 years she remained in Scotland overseeing the education of the children while Hetherwick continued alone at Blantyre. He once explained that since they were both only children, they had no relatives to whom they could entrust the care of their son and daughter. [10] Having spent her entire adult life in Blantyre, Elizabeth had to adjust to a new life in Scotland at the age of 50. Only periodically were the couple reunited when Hetherwick returned to Scotland for furloughs in 1917-19 and 1923-24. By the mid-1920s the children had grown up and the family began to think it could be possible for Elizabeth to come back to Blantyre. Medical advice, however, led them to conclude that it would be unwise for her to return. She never saw Blantyre again. In 1928 Hetherwick retired to Scotland, allowing the two of them to be reunited for the final decade of his life. They made their home in their native city of Aberdeen and assumed a senior role within Scotland’s missionary community. After Alexander’s death in 1939, Elizabeth moved to Edinburgh to be near Clement and his family until her own death at the age of 84 in 1945, by which time she was the last remaining member of the missionary group that had started Blantyre Mission in the 1870s.

Kenneth R. Ross

Notes

- John McCracken, “Class, Violence and Gender in Early Colonial Malawi: The Curious Case of Elizabeth Pithie,” Society of Malawi Journal 64/2 (2011), 2-3.

- Andrew Chirnside, The Blantyre Missionaries: Discreditable Disclosures (London: Ridgeway, 1880); Andrew C. Ross, Blantyre Mission and the Making of Modern Malawi (Blantyre: CLAIM-Kachere, 1996, repr. Mzuzu: Luviri Press, 2018), 49-79.

- McCracken, “Class, Violence and Gender,” 9.

- Life and Work in British Central Africa, February 1888.

- McCracken, “Class, Violence and Gender,” 11.

- See Alexander Hetherwick, The Romance of Blantyre: How Livingstone’s Dream Came True (London: James Clarke, n.d.), passim.

- Life and Work in British Central Africa, October 1899.

- W.A. Elmslie to Alexander Hetherwick, 16 April 1900, Malawi National Archives 50/BMC/2/1/33.

- W.P. Livingstone, A Prince of Missionaries: Alexander Hetherwick of Blantyre (London: James Clarke, n.d.), 86.

- Alexander Hetherwick to A. Melville Anderson, 22 April 1919, Malawi National Archives BMC/50 /2/1/164.

Bibliography

Hetherwick, Alexander. The Romance of Blantyre: How Livingstone’s Dream Came True. London: James Clarke, n.d. Livingstone, W.P. A Prince of Missionaries: Alexander Hetherwick of Blantyre. London: James Clarke, n.d. McCracken, John. “Class, Violence and Gender in Early Colonial Malawi: The Curious Case of Elizabeth Pithie.” Society of Malawi Journal 64/2 (2011), 1-16. Ross, Andrew C., Blantyre Mission and the Making of Modern Malawi. Blantyre: CLAIM-Kachere, 1996, repr. Mzuzu: Luviri Press, 2018.

This article, submitted in June 2022, was researched and written by Kenneth R. Ross, Professor of Theology and Dean of Postgraduate Studies at Zomba Theological College in Malawi.

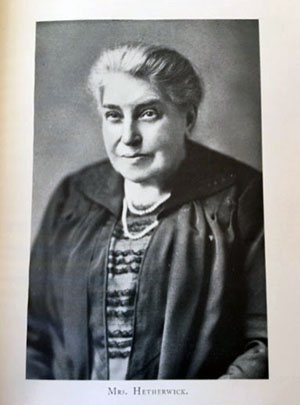

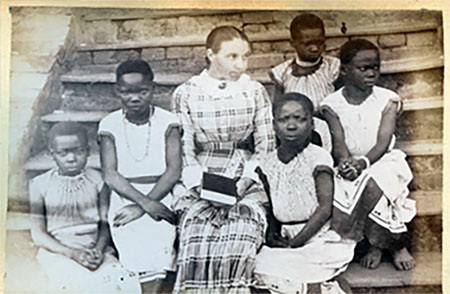

Photos:

a. E. Hetherwick

b. Reproduced by kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.