Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Hinderer, Anna

The English wife of the nineteenth century

missionary to the Yoruba country, David

Hinderer, Anna Hinderer (née Martin) was born in Hempnall,

Norfolk, on March 19, 1827. She lost her mother at the age of

five and was brought up by her father. At twelve she moved over

to reside in the home of her grandfather and aunt, Rev. Francis

and Mrs. Cunningham, in the parish of Lowestoft, England. [1]

Her religious formation, which was temporarily slowed down by

her mother’s death, received new impulse from her residence

with the Cunninghams. The church environment made strong impression

on her, and very early she grew desirous of making something

of her life for God’s service. But she perceived that her adopted

parents would consider her too young to do anything presently.

She later wrote about these early days in Lowestoft:

The English wife of the nineteenth century

missionary to the Yoruba country, David

Hinderer, Anna Hinderer (née Martin) was born in Hempnall,

Norfolk, on March 19, 1827. She lost her mother at the age of

five and was brought up by her father. At twelve she moved over

to reside in the home of her grandfather and aunt, Rev. Francis

and Mrs. Cunningham, in the parish of Lowestoft, England. [1]

Her religious formation, which was temporarily slowed down by

her mother’s death, received new impulse from her residence

with the Cunninghams. The church environment made strong impression

on her, and very early she grew desirous of making something

of her life for God’s service. But she perceived that her adopted

parents would consider her too young to do anything presently.

She later wrote about these early days in Lowestoft:

I longed to do something. I had a strong desire to become a missionary, to give myself up to some holy work, and I had a firm belief that such a calling would be mine. I think this was from a wish to be a martyr; but I wanted to do something then. Dear Mr. and Mrs. Cunningham knew little of me then; they looked kindly at me often…I often thought if I might have a few little children in the Sunday school to teach, it would be an immense pleasure. I was afraid to ask it, but having my aunt’s consent, when I was between twelve and thirteen, I ventured one Saturday, after passing dear Mrs. Cunningham three times, to make my request, fearing all the time that she would say I was too young, and too small; but what was my joy when she smiled so kindly upon me…and told me to go to the school at eight o’clock the next morning….I was up early enough; a heavy snow was upon the ground; but that was nothing. I went, and six little ones were committed to my care… [2]

Mrs. Hinderer would also date her conversion to this period of service when, in the course of her teaching, she wondered if she herself had appropriated the lessons she was teaching the younger ones:

I felt the want of something to make me happy, something that the world could not give; and I think, while talking to these little ones of Jesus, it entered my mind, “Had I gone to Him myself?” I went on seeking and desiring, and often said and felt “Here’s my heart, Lord, take and seal it; seal it for Thy courts above,” and I was comforted in the sense that God would do it. This was doubtless the movement of the Blessed Spirit in my soul. I saw my need of a Saviour, and in the Saviour I felt there was all I needed, and I was by degrees permitted to lay hold on eternal life… [3]

Although she was acutely aware of her sinfulness, which was typical of evangelical Christianity of her day, Anna Martin found purpose in her increasing occupation in the vicarage and the godly influence radiated by Mrs. Cunnigham who treated with “sweet dignity” the visitors that daily streamed into the vicarage. Diligence, respect and compassion were the legacies bequeathed her by the venerable couple, [4] and how much of these she imbibed would become manifest when her missionary aspiration was realized some twelve years later.

On October 14, 1852, she married Rev. David Hinderer of Schondorf, Wurtenberg, Germany; a missionary of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) who had briefly returned to Europe to fully prepare for service in the Yoruba country. She was deliberate and resolute in her commitment to the young missionary who had just located in Ibadan the possible place of his lifelong vocation. Happily, the years of residence and children work in Lowestoft had prepared her for what would be her peculiar assignment as she labored alongside her husband.

Entering the Lion’s Den

After her temporary stay at Abeokuta waiting for her husband to get their house ready in Ibadan, Mr. and Mrs. Hinderer finally arrived in the town at the end of April 1853. They received a rousing welcome, full of excitement,

[A]s soon as we touched the town there was such a scene, men, women, and children shouting and screaming, “The white man is come!” – “Oibo ‘de!” and “The white mother is come!” and then their thousands of salutations, everybody opening eyes and mouth at me. All seemed pleased, but many frightened too when I spoke; they followed us to our own dwelling place with the most curious shouts, noises, and exclamations. All seemed perfectly bewildered; horses, sheep, goats, did not know where or which way to go. Even the pigeons looked ready to exclaim, “What is happening?” [5]

Mr. Hinderer had had a foretaste of his missionary environment during his five month reconnaissance visit to Ibadan in 1851, and he knew there were obstacles to overcome before his mission would be firmly established there. In addition to the possible conflicts conversion from indigenous religions might generate, the Muslims too mounted open and subtle opposition to the mission. And although Ibadan’s domination of the country was a potential advantage to his plan, since, by extension, it opens the country to his missionary exploit, the social values of the people were inimical to his message. Mid-nineteenth century Ibadan was a violent society. Rustic and completely out of touch with the outside world, the town was under a military aristocracy. Yoruba religion and Islam held sway among the people, both of which were being practiced in syncretistic union. Toughness was regarded as manliness and the warlords of the day hardly exercised restraints in pursuing their ambition. The cost was the ruthless decimation of the country in fratricidal wars of conquest, plunder, and slave raiding.

The missionary couple adopted a two-prong approach to the evangelization of the town. Regular street preaching was addressed at adults. But the agency that would root the work in the country must be developed from the rank of the children who had not been fully socialized into the prevailing culture of violence. As Mr. Hinderer led the mission but concentrated on the work of the church, Mrs. Hinderer derived a fulfilling ministry in working with children whom they boarded in their modest house at Kudeti station.

The first two children they received into their home were given them by a young war chief, Olunloyo. He committed his six year old daughter and four year old son, Yejide and Akielle respectively, to the couple. Yejide insisted on returning home at the end of the first day with the missionaries and persuaded her younger brother to follow her back home, because she had been told that white people eat human beings at night. Akielle, at first, followed her counsel but soon returned to the mission house while her sister passed the night with her parents. Yejide was only convinced of her safety with the missionary couple when she returned the following day and found her brother alive and well.

It is not certain why Olunloyo gave his children to these strangers in town, about whom many were still uncertain. [6] It may not be possible to ascertain his motive, since he did not live long enough to commit himself to Christianity. However, he was deeply committed to the well being of the missionaries and did all that was within his capacity to see them fully settled in the town. He appears like one of those drawing close to the light of the gospel by degrees when death took him away in the battlefield while the couple was away to England between 1856 and 1857. He only had a foretaste of what conversion could mean when Akielle refused to participate in one of the family’s traditional sacrifices after taking residence with the Hinderers. His quiet acquiescence in the face of his son’s vehement refusal is the only evidence that a longer acquaintanceship with the mission might have led him in the way of the new faith. However this relationship is understood, Christian tradition in Ibadan today rightly recognizes his children, Yejide and Akielle, as the first converts to Christianity in Ibadan. [7]

Another child that resided early with the missionary family was Laniyonu, the son of Mele, a difficult neighbor of the mission. Mele was once very influential in the politics of Ibadan, but he fell into bad times and had to relocate to the fringes of the town. His misfortune demonstrated the delicate and ruthless nature of Ibadan politics. At any rate, his son was among the children who came to live under the roof of the Hinderers. The fourth child was an orphan and a brother of the mission schoolmaster. Within the first month of her residence in Ibadan these four children were entrusted to the care of Mrs. Hinderer. [8] Although she was still an object of curiosity with the womenfolk, she had no doubt that they loved and appreciated her; hence, she could write soon after arriving in the country about “their kind and respectful and really polite way of speaking, and…their tender and affectionate feeling towards me…” [9]

Swimming against the Current

In spite of the initial acceptance the missionary couple received on arriving in Ibadan, three major challenges soon confronted them. The first was the challenge of ill health. Mrs. Hinderer experienced her first bout of seasoning fever barely a week after arriving in Lagos on January 5, 1853; this delayed the couple’s movement to Ibadan via Abeokuta. During her temporary stay at Abeokuta she saw what would become a familiar pattern in serving as a missionary in the country: the deaths of missionaries as a result of the tropical environment that was not conducive to the constitution of Europeans. And both she and her husband had many health breakdowns and near-death experiences throughout their time in Ibadan. The missionary couple and their colleagues and assistants in the town, therefore, spent much time nursing one another as illnesses incapacitated them at turn, with Theophilus Kefer becoming, in May 1855, the first fatality in their team. [10]

The second major challenge in their early years in the country was the social ambivalence of the people towards the mission. On the one hand, they enjoyed the novelty of having this exotic species of human beings in their town and did not cease to be intrigued by their novelties in religious practices and building construction. On the other hand, many were afraid of the radical nature of the religion they were promoting, which some considered dangerous and socially drab and weak, fit only for women and children. [11] They feared that the abandonment of the tested ways of the ancestors could incur their wrath and those of the traditional divinities. Expectedly, the priests of traditional religions were not wanting in intensifying this fear. Moreover, the Christian ethos was at variance with the social ethos of the ambitious younger generation who wanted wealth and fame, which were easily attainable through their wars of pillage and conquests. The perceived intrigues of the Muslim clerics, who were connected with political authorities in the country, added to these problems as they did not like to see Christianity rooted among the people.

The third challenge to Mrs. Hinderer’s work flowed from the second. Domestic persecution of the converts erupted with the success of the mission as the Christian message made its slow but sure inroad into Ibadan society. Although there were no town-wide persecutions like those of 1849 Abeokuta, the years 1855 and 1856 were particularly difficult for the mission.

These challenges undermined Mrs. Hinderer’s work and occasionally slowed it down. Recurrent illnesses made her sometimes unavailable to the children, and inconsistencies in enrollment at her school bothered her. Whereas four months after her arrival in Ibadan, the initial rank of four pupils she started with had swelled to sixteen in August 1853, [12] enrollment fell with her absence to Abeokuta to recuperate her health early in 1854. This was in contrast to earlier expectation of receiving seven more children to the home after the completion of the bigger house Mr. Hinderer was working on. When she returned to the new and bigger accommodation in May, after a few weeks in Abeokuta, she discovered that two of her boys, Adelotan and Abudu, had been withdrawn by their parents. The former was not allowed to appear around the mission while Abudu approached his teacher with grief that his father had effected his withdrawal. [13] Ifa had told his parents at his birth that Abudu was to be a “book boy,” and they had consequently given him a Muslim name, Islam being the only religion of book known to the country then. [14] Apparently with the coming of Christianity they had thought of another possibility, hence their sending him to the mission. But the social ambivalence of the age threatened his continued residence at the mission. Happily, he eventually found his way back like his companion, Laniyonu, who was also withdrawn for a time by his contentious father, Mele.

In the heat of the domestic persecutions directed at the converts, three more boys were withdrawn by their parents early in 1855, ostensibly at the instruction of local divinities but actually at the counsel of the local priests whose trades were under threat. When, the following year, another boy who was sick was taken from Mrs. Hinderer, she lamented her loss:

You must share my sorrow…Another little boy has been taken from me by his heathen parents, a child who has been a long time with me. The worst is, I can never see him, he does not come near me, so that I cannot tell whether his heart is still with us, or whether he has been turned to former fashion [i.e. Yoruba religions]. It is a sore trial to me, I have felt I would rather have laid him in our quiet burial ground. [15]

This spate of withdrawals was, however, compensated for by additions from unexpected quarters. When the missionary couple visited Oyo in 1856, just before their vacation in England, a small girl became endeared to Mrs. Hinderer and pleaded that she be allowed to follow her to Ibadan. At the Alafin’s permission, Konigbagbe returned with them to the mission in Ibadan. Additions also came from the opportunity to redeem some traumatized child slaves in Ibadan. This did not only compensate for their loss, but it also publicly brought to the fore the contrast in the values of mid-nineteenth century Ibadan society and those the missionaries were commending to the people.

Life where Death Reigned

A unique value the missionaries were promoting in Ibadan and which readily struck the people was the work of mercy the missionary couple made part of their missionary work. The perennial slave-raiding wars of Ibadan produced a large slave population in the town some of whom eventually survived their ordeals and were integrated into families. This happened mostly where women slaves became additional wives in the households of their masters. But many also did not survive. Hunger and diseases wasted some, and there were occasions of abandonments when slave owners considered their captives too costly to maintain for reason of their ill health. A few women in such situation were given succor in the mission and were nursed by Mrs. Hinderer. The children, however, benefitted most from this rescue mission and became part of the fledgling mission community. The story of a small girl and her mother from the Efon country, that is Ekitiland, well illustrates one of such works of mercy.

In 1854, Ibadan war boys raided the country with fierce violence, destroyed the towns, captured many of the people and brought their victims home as slaves. During the raid, a woman and her daughter fled into the forest to avoid being captured. Their husband and father seems to have fallen in the puny resistance their town mounted against the overwhelming force of their assailants. After several days in the forest, surviving on leaves and roots, they decided to take their rest under a tree. Two of the invaders suddenly swooped on them and quickly tore mother and child apart and escaped in different directions. They did not listen to their plea for mercy. The unhappy seven year old girl was brought to Ibadan as a slave. A convert of the mission who himself had come to Ibadan as a slave tried, though unsuccessfully, to cheer her up; but she remained disconsolate. When he heard that her owner was about to sell her to traders going to the coast from where she might never be retrieved again, he went hastily to Mr. and Mrs. Hinderer to explain the situation. He encouraged them to redeem the girl as he had no money to effect her ransom. The couple gave him the money, and in no time he appeared at the mission with the child.

The poor child was initially terrified at the presence of her “white” benefactors; but with the cheerful encouragement of the other children in residence, she was assured that at the mission she would never be a slave. Ogunyomi soon became a happy girl in the Hinderers’ home, intrigued by the songs and the alphabets she was learning and the magic of needle work. But with time, she fell into melancholy again. When she was asked the reason for her cheerless mood, “She burst into tears ‘Iya mi,’ ‘iya mi!’”–“My mother, my mother!” Mrs. Hinderer encouraged her to pray to God to bring her mother if that was his will for her. Such prayer was a tall order in a town of over one hundred thousand people and where slaves were often given new names on arrival. The chance of such reunion was extremely low, if not impossible. But providence had not yet finished with Ogunyomi.

Six months after she had taken residence at the mission, she went to the nearby Kudeti stream with her mates to draw some water. A woman was passing by who was intrigued by the children’s white dresses. But, more than that, she heard a voice that sounded like her daughter’s among the lively chatters of the children and took time to listen very well. She recognized the unmistakable voice of her supposed lost child and exclaimed, “Ogunyomi!” Ogunyomi turned around at the direction of her caller and stared for a moment at her. On recognizing that it was her mother, she rushed into her lively embrace, screaming “Iya mi, iya mi!” The other children made a hasty return home shouting, “Ogunyomi has found her mother!”

Ogunyomi’s mother was told all the missionaries had done for her daughter, and she recounted her own journey into slavery in Ibadan. She rejoiced at the redemption of her daughter and paid her regular visits. But soon these stopped and Ogunyomi fell back into her melancholy. The missionary couple investigated the reason for her stopping the visit and found that she had become seriously ill beyond any hope of recovery. For the sake of her daughter, they paid her ransom fee and brought her to the mission where they nursed her to life again. On recovering they employed her as a domestic helper, cooking for the children. Lucy Fagbeade became a Christian and happily lived in the mission with her daughter until her death in 1867. She lived to serve the mission for eleven years. [16]

Sophie Ajele’s story was a direct contrast to Ogunyomi. When the missionary couple was away to England in 1856, their catechist, James Barber, took in a little girl because her mother wanted to sell her. When the matter was taking before the chief, the father agreed that the missionaries could take her up if they were willing. Before her adoption to live in the mission, she had suffered neglect. She had measles and for three days her mother refused to give her food. After she was received into the mission, the mother relocated to Ijaye and was not seen for a long time. Then she sneaked into town to steal the child away, but found her still with measles. She pretended to have come to take care of her. When she began to rain abuses on her daughter’s benefactor she was forced out of the mission compound, but not until she had administered to her daughter a dangerous dose of poison. Days later, she returned and the same scenario of verbal abuse played out again. The poor girl held tenaciously to Mrs. Hinderer, begging her not to allow her mother to take her away because she would only sell her away.

Sophie was an affectionate child who took interest in always sitting near her adopted mother, gazing at the picture of Jesus blessing children. But she had a weak constitution and eventually succumbed to the fatal scourge of the disease that wasted her. Yet her short spell in the mission gratified Mrs. Hinderer who gave her utmost attention and care. She and the other children were affected by her death. The same evening, when she died, Mrs. Hinderer wrote that she and the other children in residence, “followed her to the silent grave, where we laid her just as the shades of night were coming over us.” [17]

The stories of Ogunyomi and Sophie are not isolated cases of the Hinderers’ acts of mercy. Several others reaped from their home. In 1854, they retrieved Arubo and brought to the mission this “cold, starved, and filthy” slave boy who was thrown out of a compound and was pleading with passers-by on Ijaye road to buy him. [18] The following year, another smart boy was redeemed from slavery and found security in living with Mrs. Hinderer. [19] About the middle of 1858 when Mr. Hinderer was touring the interior to prospect for mission posts, Olubi retrieved a little baby, less than a week old, abandoned by a stream. Suspected to have been thrown away because he was a twin child, he was brought to the mission where Mrs. Hinderer nursed him for three weeks. He had suffered much through the cold night and eventually died. [20] Still, in the war years that followed that of Ijaye, another child, about six months old, in similar circumstances was retrieved from a stream in 1864. She rallied again to full health and was given the name Eyila, meaning “this is saved.” She became a bundle of joy in the mission. [21]

The rank of children in Mrs. Hinderer’s school also swelled from the additions to the families of the agents. When the couple was returning from their vacation in England in 1857, they stopped over in Sierra Leone where they recruited two agents, Mr. Henry Johnson and Mr. William S. Allen. The two families brought to Ibadan six children. [22] The growing family of Daniel Olubi, their much trusted servant and agent, continued the expansion, first in Daniel, Jr. and, then, in Bertha.

But male and adult sufferers of the age also benefitted from the home of the missionary couple. Antonio, a former slave and returnee immigrant from Brazil, and his family found shelter with the mission, away from the hostility of his relations. Although he spent much of his time on his farm, for ten years he found refuge with the missionary couple and converted from his catholic faith to evangelical Christianity. Antonio died in 1867, and he was soon followed by his wife. The missionary couple took care of their two children–Talabi, a girl, and her brother–whom their unconverted, extended family members wanted to inherit as slaves. Mrs. Hinderer described Talabi as “a wonderful trouble, ten Topsies in one…I have much anxieties, now that she is growing up.” [23]

Mother, Playfellow, and Teacher

Mrs. Hinderer took a lively interest in her children and they soon grew fond of her. She managed the first team she had from 1853 as a playgroup. When she gave them a break at the end of the year, the children did not like the fact they would miss their time with her. When she gave them the option of coming from home to take lessons, they readily jumped at the offer. They found her stories and lessons stimulating. In the midst of the multifarious demands on her as the mother of the mission, the presence of the children was her most pleasant joy. “Our home life is one of privation,” she wrote early in 1855, “and often of trial and difficulty, but a very occupied one, and one of much hope and interest.” “I have not time to be idle, truly,” she continued, “and I think never a night has come without my being thoroughly tired…The dear children are my greatest outward comforts. I like to hear them singing, not with the taste and mellowness of our English children, yet with much heart and real enjoyment.” [24]

Mrs. Hinderer’s education program for her children was a total one. She gave attention to their grooming and demeanor, and spiced their training with music. The girls were also introduced to needlework. They initially found daily washing “unheard-of absurdity,” but with discipline they soon got entrenched into the regimen. [25] Coming also from a society where noise and chattering was the norm, they thought it strange to be ordered to be quiet and silent. It was at the family prayers that their appreciation for silence began to emerge, and Mrs. Hinderer wrote soon after a few months of gathering them, “Nothing composes them so much as music. We always sing a hymn with the harmonium at prayer, with which they are delighted. But though decidedly a care and no slight trouble, I would not for anything be without them; they will lose their wildness in time, and they are so affectionate.” [26]

When the couple returned from their trip to England in January 1858, Mrs. Hinderer was happy for the management of her children and school in her absence by their catechist, Barber, and Olubi and his wife. She even saw the evidence of the Spirit at work in the life of the children. Unlike the depressing situations they left behind in 1856 because of the intense persecutions of their converts in their homes, things looked up in 1858. Although they returned shortly before the hot season set in, they coped very well, possibly because the mission and its converts were less troubled this time. Evidently, the spirit was also at work in the wider community as more people began to appreciate their work and acceded to the church. In February 1858, she was reporting on 27 children in her care; few months after, she wrote, “My thirty children are very prosperous, very good, very naughty, and very noisy, just as it happens…” [27]

Mrs. Hinderer continued to take joy in working with her children and delighted in their company. She once wrote, “I do wish you could see my children, we take great pains with them, and they are in some order, and are getting on very well. They are always about us, and out of school hours I can never stir without a flock around me.” [28] In her teaching, she drew lessons from nature and used picture illustrations she brought from England, and these both delighted the children and brought home the lessons she was passing across to them. [29] It was at the height of the domestic persecutions that eight of them were baptized along with six others on November 9, 1855. Mrs. Hinderer decked her children–Onisaga, Akielle, Laniyonu, Arubo, Elukolo, Abudu, Ogunyomi, and Mary Ann Macaulay–all in white for the occasion. It was a significant event in which some of the neighbors of the mission came to acknowledge the futility of their conspiracy to keep their people from going to the mission. [30]

Times that Try the Soul of Men

The work of the mission was on a good footing and arrangements were being made for expansion into the interior when war broke out between Ibadan and its neighbor, Ijaye, in January 1860. In the alliances that complicated the war, Ibadan was shut in by their Egba and Ijebu neighbors to the south. The drumbeat of war reminded the missionaries how much still needed to be done to transform the bloodthirsty town into a city of peace. Meanwhile, the war brought the mission much woes. At first, Mrs. Hinderer stored food in the house for her children, and they had a large store of cowries to meet their purchasing needs. But as the war became protracted the store steadily grew empty and the cowries were exhausted; the war did not restrain the children’s appetite. [31] With her husband’s illness at hand and the need to continue to care for those children who had nowhere else to go, she was occupied with domestic affairs. The gifts sent from England by Lady Buxton could not be delivered for the fear of their being impounded on the way to Ibadan. Eight months into the war, she wrote with near despair, “Our future looks very dark.” [32]

The year was indeed a tough one for the missionary couple, and Mrs. Hinderer was emotionally stretched. As the year wore on and the economic situation of the town became increasing difficult, the Christian band suffered bereavement in the death of a woman who had been badly persecuted by her family members for becoming Christian. The incident became useful in the hand of the people as they criticized the missionaries when they could not raise her back to life again. They wondered what value was in a religion that made people to abandon the good ways of their fathers only to be struck dead by the gods while the missionaries could not bring the person back to life again? At the same time, another woman lapsed from faith because of the overwhelming persecution of her relations and returned to good health afterwards. These two incidents gave the critics of the mission occasions to triumph. [33]

The social environment of war was particularly distressing as Mrs. Hinderer wrote, “We are weary with war, sounds of war, talks of war, anticipations of war; but we have been mercifully kept and comforted.” [34] Of all their woes, the unrestrained bias of the Egba elements in their mission was most troubling, because it brought the conflicting sentiments of war mongers under their very roof. [35] And, much more, the missionary couple found it embarrassing and Mr. Hinderer had to keep it under control as it was a major threat to the continuous existence of the mission. With all these troubles at hand and the store of cowries greatly diminished, Christmas was not celebrated in December 1860. [36] But the Christmas day service held with the children “in church, washed, and oiled, and dressed in their very best, their wooly hair freshly plaited (which sometimes is not done for months altogether), and looking as cheerful as possible…” [37]

Mrs. Hinderer had to be resourceful in providing for the seventy mouths for which the mission was responsible–herself and her husband, the children in the mission, and the agents and their families. She devised various ways of preparing yam for meal to make it palatable and managed with beans and palaver soup while her husband relished the Indian corn flour made into porridge. There were enough of these foods in town, but there were no cowries to purchase enough. [38] An attempt to take loans from the chief saw Mr. Hinderer visiting the camp on the eve of the New Year, 1861. Although Ifa forbade giving him the loan he asked for, some of the chiefs gave personal donations in acknowledgement of his person and the good work he was doing in the town. [39]

With the evident proof that the situation in the mission was no longer sustainable, Mrs. Hinderer sent back home all the children in her custody who had parents to support them. From home they came to school daily. Another woman volunteered to take an orphan to herself to relieve the pressure on Mrs. Hinderer. [40] The dire situation was also an occasion to reproach them by people for whom lack of trouble was a sign of favor with the gods. They say, “What is the use of their serving God? They die, and they get trouble; and Ifa and Sango, &c., &c., often help us. The Mohammedans say, God loves us well, but we do not worship Him the right way, and do not give honor to His prophet.” [41]

In the adverse situation the couple found themselves, Mrs. Hinderer began to sell some articles in the home some of which she had earlier considered useless; but now she knew the people would like to buy them. She and the children brought out and spent hours in polishing old tin match-boxes, biscuit boxes, and the lining of deal chests. When they exhausted selling these, they began to dispose household utensils for cowries at prices below their values, just to have cowries to buy food. [42] Later, she sold her gown to get cowries worth just £1, far below its value. [43]

But there were also occasional supports from unexpected quarters, such as gifts of cowries from a member of the church and loan from a relation of their agent, Olubi. On one of those difficult days she received gifts of Indian corn from a woman passerby who was impressed that she could speak her Yoruba language and entered into an interesting conversation with her on her mission in Ibadan. Another assistance came from her milk supplier who, although would never want to hear the gospel, insisted on supplying her household their need for milk at no cost to them for one full year. When Mrs. Hinderer later sent her some cowries in recognition of her services, she refused to take the payment saying, “I did it because you were strangers in a strange land, and I will not take anything for it.” [44]

Their woes deepened with months and years. When Mr. Hinderer undertook a dangerous trip to Lagos in March 1861 through the forbidden territory of Awujale, the Ijebu king, he lost much of what he got. The caravan he used to send them to Ibadan was attacked and he lost his provisions. What he got for money in Lagos to change to cowries was swindled by the Ijebu trader who promised to bring him cowries in Ibadan. He was only mercifully protected himself on the journey as the Awujale set a price on his head for staying in Ibadan and daring to pass through his territory to the coast. His successful return, though near empty-handed, elicited rapturous joy throughout the town; and gifts of food and cowries poured in for the mission from all quarters in celebration of his safe arrival. [45]

Years passed on, and although Ibadan succeeded in destroying Ijaye in 1862, the conflict continued on different fronts with the Egba and Ijebu peoples; and Ibadan remained shut in. Mr. and Mrs. Hinderer remained at their post, but not much could be done to advance the mission except to keep it running. Survival became paramount in the face of recurring illnesses of both of them. But creativity was not all lost although everything that could fetch them cowries had been disposed of. The children continued their lessons and Mrs. Hinderer cultivated beds of onions, which one of the women in the church sold for her, again far below their values just to have cowries to purchase food. [46] Between 1862 and 1864, attempts by the colonial administration of Captain Glover in Lagos were made impossible by the hostility of the Ijebu king who would not give his embassies passage. Their missionary colleagues at Abeokuta too were half-hearted in relieving them, having taken side with their Egba hosts in the feud. [47]

The work continued, however, but there were no teaching materials for the children. They had no Bible, and Mrs. Hinderer’s stock of teaching aids had worn out by 1864 and had to be carefully held together while teaching. Happily, the children were making good progress in their religious and temporal education. [48] It was in the midst of these woes that the tiny tot, Eyila, was retrieved from the brook and brought to the mission.

Relief finally came to the couple in April 1865 when the governor sent his officer, Captain Maxwell, to Ibadan to fetch the missionary couple. Maxwell cut through the pathless forest to reach Ibadan at 10.00pm with provisions for the couple to make the journey back the next morning. Caught unawares by the governor’s provision, only Mrs. Hinderer could make the journey so hastily. She had to set out very early before the enemies became apprised with the venture and before the children woke up to make parting difficult. But Konigbagbe, the eldest of the lot, accompanied her mistress on the non-stop match to the coast. Mr. Hinderer stayed for few more weeks to make his own exit, after making arrangements for the mission in his absence.

The return to England offered them opportunity to recoup their health and to visit friends, both in England and in Germany. It was also an opportunity for them to raise support for the impoverished Ibadan Mission and their work with the children. While they were doing these things they were receiving news of the proceedings at Ibadan. The first news they received in their mail was the death of Arubo, the boy they had rescued from starvation on Ijaye road eleven years before. In these years he had made significant and all round progress in his formation under Mrs. Hinderer. The next mail brought them the sad tiding of the death of Eyila, the little baby that had grown fond of Mrs. Hinderer. [49] Mr. Hinderer had recounted to his wife on arrival in England that she could not understand her “mother’s” absence at first. At daybreak, on the day Mrs. Hinderer left Ibadan, Eyila:

[C]ame joyfully into Mr. Hinderer’s room, thinking her Iya would be waiting to give her the usual greeting; but when her bright eyes looked for her in vain, she climbed on Mr. Hinderer’s knee, and throwing her arms around his neck, sobbed convulsively. She could only explain her grief by leading him to the door, to make another vain search for her Iya on the road by which she had seen her set out. [50]

Winding Down

Mrs. Hinderer returned with her husband to Ibadan again in December 1866, having been away for about eighteen months. The mission and the converts remained steady, and Konigbagbe was now married with a child. [51] By February 1867, she was in full force again:

Three of the boys are learning harmonium; it is a work of patience…I have Akielle and Oyebode every morning for lessons, general history, geography, Nicholl’s Help, &c., the girls for sewing from twelve to two o’clock, and I am now forming a class of women who live near us, to teach them to sew, once a week. These are some of the regular doings, and the irregular may be called legion, doctoring [i.e. nursing the sick and wounded], mending, housekeeping, receiving visitors. [52]

One of the fruits of their trip to England was the printing of the Pilgrim’s Progress in Yoruba language, the translation of which Mr. Hinderer undertook with his agent, Mr. Henry Johnson, during the wars that shut the mission in from 1860 to 1865. Mrs. Hinderer reported that her class of women on Sunday afternoons “were greedy for it; we each read a paragraph, and talk about it; and on the Sunday evenings, after a little scripture repeating, and hymn-singing, I read it with my girls and D. with the boys; they are perfectly charmed.” She goes on to write that, “Their open mouths and exclamations, when the full meaning of something in it presents itself vividly before them, are most entertaining.” [53]

Things were easing up for the mission in Ibadan when the riot broke out in 1867 at Abeokuta, during which the churches were plundered and destroyed and the missionaries were prohibited from the country by the Egba and Ijebu authorities. The rampaging elements at Abeokuta sent some of their loots to the chiefs in Ibadan indicating to them to do the same to the mission in their midst, but Ibadan authorities acquitted their missionaries. [54] Nevertheless, the mission lost its momentum under the missionary couple after this incident. Ill health plagued them over and again, and the same privation they experienced before they returned to England played out before them as Ibadan was shut in again for entertaining their presence in the country. Yet, there were occasions for joy.

By the time they returned from their trip to Europe, some of the children they had trained were coming into service with the mission. Hethersett Laniyonu, one of the earliest recruits of 1853, and Samuel Johnson, who joined them in January 1858 from Sierra Leone, had finished their studies at Abeokuta Training Institution in December 1865. Laniyonu and Konigbagbe were serving at Ogunpa as schoolmaster and mistress there and were making an impact. Mrs. Hinderer wrote, “Koni is so energetic; she had my best powers spent on her, and she is capital. Laniyono is doing well, persevering and industrious.” [55] Samuel Johnson too was serving at Kudeti, another sign of hope for a virile indigenous leadership.

However, the year 1868 was one of mixed blessings. In spite of the hard times, Christian witness was gently but steadily penetrating families and compounds through the quiet work of the converts in their homes. [56] The unconverted were taking more interest in the message and were asking questions as never before. Adeyemi of Katunga, an old prince of the defunct Oyo metropolis, embraced the faith after many years of belligerent argument against it and was baptized on Advent Sunday, November 30, with seven other candidates. Mrs. Hinderer was cheered by these silver linings in the horizon.

But bereavement also struck the mission in the death of one of the young girls, fourteen year old Moleye. [57] Soon after, two of the “big boys” in the mission lapsed from the faith and veered into dark, pagan practices. [58] Ill health also continued to ravage the lives of the couple. In fact, it became clear in 1868 that Mrs. Hinderer’s health had become materially damaged, and it would not be possible for her and her husband to remain in the country much longer. Hints on their situation again reached Governor Glover in Lagos, who, possibly with the solicitation of the missionaries now restricted to Lagos, planned their exit. As in 1865, he sent a secret expedition that cut its way through the forest to fetch them to the coast, arriving unexpectedly in Ibadan on New Year’s eve. And still because they were unprepared for the arrival of the mission, only Mrs. Hinderer, who was in a bad state of health, returned with them to Lagos on January 5, 1869, closing her seventeen years of service in the Yoruba country. [59] Less than eighteen months after, she passed away in Martham, Norfolk, in England, on June 6, 1870.

The Legacy of Anna Hinderer

By giving her energy to the nurturing of the children in Ibadan, Mrs. Hinderer chose to invest in the future of the work. Her impact can, therefore, be assessed mainly by following the track of those who profited from her spiritual, moral, and intellectual formation. From this perspective, her success can only be judged as modest. For she herself knew that not all the children that came under her care turned out right. Among classical failures, Laniyonu ranked first. He showed much prospects as a child and as a trained agent of the mission, only to derail and bring the faith into disrepute. When he was dismissed from the service of the mission in 1868, he was one failure too many for Mrs. Hinderer who lamented, “These are deeper and more heart-searching trials than anything from the poor heathen.” [60]

Nevertheless, others who profited from her vindicated her training and went on to become the pillars of the mission. Samuel Johnson, Laniyonu’s colleague under Mrs. Hinderer’s teaching from January 1858 and at Abeokuta, became the schoolmaster at Kudeti, catechist at Oke Aremo, and the first ordained pastor placed in charge of the church at Oyo from 1886. Johnson may be said to have fulfilled the deep aspiration of the missionary couple in his contribution to the attainment of peace in the war-torn country from 1888. To this may be added his exploit in documenting for future generations the history of the Yoruba nation, a venture that also fulfilled the deep desire of Mr. Hinderer.

Robert Scott Oyebode became the schoolmaster at Aremo and was ordained in January 1895. [61] He served creditably well as a minister among his people in Ibadan. Francis Lowestoft Akielle, the first boarder in Mrs. Hinderer’s home, also became the schoolmaster at Kudeti in 1869 and later married Ogunyomi. [62] From the 1890s he was assigned responsibility for the church at Ogbomoso and was ordained in 1898 as a minister. [63] Apart from Samuel Johnson who died an untimely death in April 1901, these contemporaries, under Daniel Olubi, rooted and strengthened the faith in the country in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, and well into the early years of the twentieth. Hence, it may be said that although not all the sprouts that came out of Mrs. Hinderer’s planting grew to fruition, those that did proved that she did not labor in vain.

Mrs. Hinderer’s memoirs were eventually published in 1870 after the compilers, Miss Hone of Halesowen Rectory and her sister, succeeded in persuading Mr. Hinderer to allow them to publish her story. The first profit realized from the sale of the book Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country, amounting to £31.4.8, was sent to Ibadan mission in July 1873 in support of the work now under Mr. Daniel Olubi. [64] And so, although dead, Mrs. Hinderer was still speaking.

Kehinde Olabimtan

Notes:

-

R. B. Hone, Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country–Memorials of Anna Hinderer (London: Religious Tract Society, 1872), 1-6. Although they did not sign the book, the real compilers were two Hone sisters who were friends and acquaintances of Mrs. Hinderer. Daniel Olubi, journal entry, July 21, 1873, CMS C/A2/O75/29.

-

Hone.

-

Hone.

-

Hone, 8-10.

-

Hone, 55.

-

Ajayi is of the view Olunloyo’s commitment of his children to the missionaries’ care for training was consistent with Yoruba tradition, which allows families to dedicate their children to the divinities. In this case, he was handing over his children to “an unknown God” the missionary couple might have come to proclaim. J.F.A. Ajayi, Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841-1891- The Making of a New Elite (London: Longmans, 1965).

-

Chief Emmanuel Alayande, interview in Ibadan in 2004. Yejide’s memory has been sustained by naming an Anglican secondary school in Ibadan after her, Yejide Girls’ Grammar School. Surprisingly, however, I find Yejide’s name hard to come by in Ibadan missionary records; not even in Mrs. Hinderer’s memoirs after the incident of the first day she was given to the missionaries.

-

Hone, Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country, 69.

-

Hone, 67.

-

Hone, 123; J. T. Kefer was another Basel trained German missionary from Wurtenberg. He was unmarried at the time of his death.

-

In 1876, Samuel Johnson noted in his journal that the people of Ibadan generally viewed Christians as “quiet people, averse to fame and worldly honor.” S. Johnson, journal entry, April 5, 1876, CMS C/A2/O58/6.

-

Hone, Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country, 81.

-

Hone, 99.

-

Hone, 85.

-

Hone, 138.

-

Hone, 292-294.

-

Hone, 188.

-

RH Hone, 104-106.

-

Hone, 124.

-

Hone, 179.

-

Hone, 275.

-

D. Hinderer to Secretaries, February 25, 1858, CMS C/A2/O49/32.

-

Hone, 302.

-

Hone, 117.

-

Hone, 196.

-

Hone, 71.

-

Hone, 178.

-

Hone, 184.

-

Hone, 120, 121.

-

Other occasions of baptism of children took place in 1860 and in 1861. On the latter occasion, five out of the eighteen baptized were Mrs. Hinderer’s charge. Hone, 128, 129, 223, 256.

-

Hone, 220.

-

Hone, 226, 227.

-

Hone, 223, 224.

-

Hone, 228.

-

Hone.

-

Hone, 229.

-

Hone, 230.

-

Hone, 233.

-

Hone, 234.

-

Hone, 234, 235, 245.

-

Hone.

-

Hone, 236, 237.

-

Hone, 255, 256.

-

Hone, 240.

-

Hone, 254, 255.

-

Hone, 256.

-

Mr. Hinderer wrote that relief materials of “cowries and substantial provisions” were sent to Ibadan Mission through Abeokuta, but the missionaries and their agents stopped their onward transmission. According to him, they claimed that “no carriers could be got for any load.” D. Hinderer to H. Venn, March 10, 1863, CMS C/A2/O49/61.

-

Hone, 276.

-

Hone, p. 283.

-

Hone, p. 284, 285.

-

Hone, p. 288.

-

Hone, p. 290.

-

Hone, p. 292.

-

Hone, p. 304.

-

Hone, 321.

-

Hone, 312.

-

Hone, 309-311.

-

Hone, 314, 315.

-

She left on January 5, 1869. D. Hinderer, Half Yearly Report of Ibadan Mission Stations Ending June 25, 1869, CMS C/A2/O49/121.

-

Hone, 322.

-

I. Oluwole to F. Baylis, March 6, 1895, CMS G3/A2/O(1895)/57.

-

Hone, 327.

-

John Peel, “Two Pastors and their Histories–Samuel Johnson and C.C. Reindorf,” in The Recovery of the West African Past: African Pastors and African History in the Nineteenth Century–C. C. Reindorf and Samuel Johnson, ed. Paul Jenkins (Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 1998), 78-79.

-

Daniel Olubi, journal entry, July 21, 1873, CMS C/A2/O75/29.

Sources:

Primary

Archives of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, UK.

Hone, R. H. Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country–Memorials of Anna Hinderer. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1872.

Johnson, Samuel, The History of the Yorubas–From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate. Lagos: CMS, 1921.

Secondary

Ajayi, J.F.A. Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841-1891–The Making of a New Elite. London: Longmans, 1965.

Church Missionary Society, Register of Missionaries.

Peel, John. “Two Pastors and Their Histories, Samuel Johnson and C.C. Reindorf.” In The Recovery of the West African Past: African Pastors and African History in the Nineteenth Century–C.C. Reindorf and Samuel Johnson, ed. Paul Jenkins, 69-81. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 1998.

Peel, John. Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Others

Interview with Chief Emmanuel Alayande, Ibadan, January 2004.

This article, which was received in 2011, was written and researched by Dr. Kehinde Olabimtan, Coordinator of educational ministries, Good News Baptist Church and Adjunct Teacher, Akrofi-Christaller Institute, Ghana, and a recipient of the Project Luke Scholarship for 2010-2011.

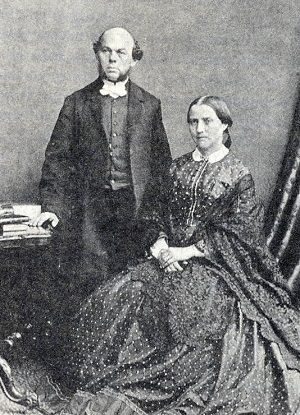

Photo Gallery

[1] Taken from Hone, R.B. Seventeen Years in the Yoruba Country: Memorials of Anna Hinderer. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1872.

[2] Taken from The Church Mission Society and World Christianity, 1799-1999, eds. Kevin Ward and Brian Stanley. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing/Richmond (UK): Curzon Press,

- Used with permission from the Church Mission Society Archives (www.cms-uk.org).