Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Dlamini, Bonaventure

The first black Catholic bishop in South Africa.

The first black Catholic bishop in South Africa.

Bonaventure Dlamini was born and educated at Mariathal Mission. The exact date of his birth is apparently unknown. [1] He was a descendant of Chief Namagaga, who had lived on the banks of Umzinyathi River in Zululand in 1812 and left for the region of Umzimkulu during the reign of Shaka. [2]

The Historical Context

At the close of the Second World War, a new situation began to emerge in Asia and Africa where the colonial powers had ruled for a century. These changes were the result of several events. First, the colonial powers had been weakened economically by the war. Second, attitudes towards colonialism had begun to change with the formation of the United Nations. Following India’s lead in 1947, African countries began to attain political independence from their erstwhile colonial masters. The first country to achieve independence was Ghana in 1957, followed in 1963 by countries in West and East Africa. By the mid-1960s, most of Africa was ruled by its own indigenous leaders. [3]

Within the Roman Catholic Church, the 1950s became a turning point in respect to indigenisation. The growth of indigenous vocations in the Roman Catholic Church had begun in 1898 when the first black priest, Edward Mnganga, was ordained in Rome. Mnganga’s ordination was soon followed by that of three more Zulu priests. The figures grew steadily, to the extent that by 1957, a total of thirty-eight priests had been ordained. Most were trained at St. Mary’s and St. Peter’s Seminaries and became African diocesans, but among this number were twelve Franciscan Familiars of St. Joseph (FFJ) and one priest from the Pallotines. The first colored diocesan priests were Henry Damon (1940) [4] and Romuald Booysen (1947), both of whom had been trained by the Pallotines at Swellendam and worked in the diocese of Oudtshoorn. [5]

With regard to episcopal matters, the Roman Catholic Church in Africa was also developing rapidly, resulting in a series of episcopal ordinations in the 1950s. In Tanganyika, two bishops had been consecrated–the first in 1951 and the second in 1956–a bishop was consecrated in Ruanda in 1952 (present-day Rwanda), one in Basutoland (present-day Lesotho), and another in Nigeria in 1953. Consecrations also took place in South Africa in 1954, and again in Nyasaland and Kenya in 1956, where each received a bishop. As Walbert Bühlmann observes: “The Latin Africa countries were somewhat hesitant until, in the French dependencies, four African bishops were consecrated in 1955-1956 and one in the Belgian Congo in 1956. Bishop Dud of Sudan, consecrated in 1955, was also an African.”[6]

After the 1970s, the ordination of African bishops became more frequent. What one needs to look at critically is the fact that it took the church almost forty years from the turn of the twentieth century to consecrate an African bishop. This could be attributed to several reasons, not the least of which was that the local church had not taken root in Africa. Again, as Bülhman comments: “The real implantation of the church has not taken place in Africa. We are not yet a ‘local’ church…We are stifled by the overwhelming presence of missionaries. We are still a colony of the church.” [7]

The Creation of the Diocese of Umzimkulu

In 1952, Archbishop Celestino Damiano, who was based in Pretoria, was appointed apostolic delegate to South Africa. Prior to his appointment, he had worked for the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith and had paid a visit to South Africa in 1950. As Brain expands: “In view of the Vatican’s policy regarding the Africanisation of the church…it can be assumed that Archbishop Damiano intended to appoint a black bishop in South Africa and, since Mariannhill diocese had the greatest number of black Catholics and also more African clergy than anywhere else in the country, it seemed probable that this was where the new diocese would be erected.” [8]

Bishop Streit of Mariannhill, and Fr. Reginald Weinmann, the Superior General, suggested that instead of creating a diocese it would be more appropriate to create an auxiliary diocese. Damiano on the other hand was determined to create a new diocese with an African bishop. From the onset, some of the Mariannhill priests [9] were against the creation of the Umzimkulu Diocese, but Celestino Damiano, an Italian-American, was “a pusher” who seems to have always got his way. According to an interview with Oswin Magrath in 1996: “Then Damiano came with orders to get a black bishop in the Republic. There was only one black bishop in Lesotho, ‘Mabathoana. Damiano did his best and carved Umzimkulu out of Mariannhill. Mariannhill took it badly.” [10]

The Diocese of Mariannhill had grounds to be against the creation of a new diocese, and the whole process caused a great deal of unhappiness among the Mariannhill priests. Damiano, in fact, had little or no consultation with the Mariannhill authorities and events took place very fast.

The Mariannhill missionaries had built their mission work in Natal for over seventy years and during this time had built several schools and hospitals. Brain explains further: “Mariannhill had been the leading light in the Catholic mission field, and had brought to the country many priests and several hundred highly skilled brothers; they had developed mission stations and schools, established their farms with funds they had generated themselves, opened mission hospitals and set up a mission press.” [11]

In the light of such developments, the general feeling among the Mariannhill clergy was that they deserved better treatment and possibly even an opportunity to air their views and be taken seriously. At the inception of Umzimkulu diocese, “there were doubts from the beginning about the suitability of the new diocese and even more about its viability.”[12] The situation was later exacerbated when Umzimkulu Diocese was also granted Lourdes, Centocow, and Emaus mission stations–all highly prized mission stations of great historical significance.

Although Damiano was overly assertive, it is also quite plausible that the creation of the Umzimkulu Diocese was for his personal gain, in the sense that if he created more dioceses, Rome would applaud his work. As Archbishop Hurley observed, it was: “…mainly the work of the apostolic delegate, Damiano. He wanted to show that he had been a successful delegate and, in those days, creating a local diocese would be very well received in Rome. It would give the delegate a good name in Rome–that was the impression we got. I have not seen any papers or documents. Certainly Damiano was very ambitious.” [13]

Accordingly, the Diocese of Umzimkulu was created. Lourdes, “the oldest mission station of Mariannhill, which once was the most extensive mission property in Natal and (had) developed in the course of (sixty) years into a grand Christian community of about 12,000 Catholics,” [14] was to become its center. The new diocese consisted of one third of the area of the Diocese of Mariannhill, with the Umzimkulu River as a natural boundary to the east. It contained the civil districts of Umzimkulu and Port Shepstone, as well as Margate at the coast and Harding in the interior. There were 30,000 Catholics at the time in the diocese, of which Lourdes, with its many outstations, numbered some 13,000. [15]

Even after the creation of the Umzimkulu diocese, the larger mission stations were still administered and run by Mariannhill priests. For example: “Fr. Xavier Brunner was rector at Lourdes, Fr. Siegfried Schultis was in charge of Centocow, Fr. Aurelius Boschert of Harding, Fr. Gabriel Bader of Emaus, and Fr. Raphael Boehmer was in charge of Port Shepstone. Some of the other mission stations were administered by the African clergy.” [16]

Bishop Bonaventure Dlamini

Dlamini was one of the first students to enter the minor seminary when Mariathal opened in 1925.[17] He completed his studies at St. Mary’s Major Seminary and subsequently joined the Franciscan Familiars of St. Joseph (FFJ). The ordination by Bishop Fleischer of Dlamini, the second FFJ priest to be ordained after Elias Mkwane, took place on November 28, 1937 [18], when Dlamini was around thirty years old.

Following his ordination, Dlamini worked at several mission stations, including Kevelaer, St. Magdalene, St. Adalbero, and others on the Natal south coast. He was also the diocesan consultor to the first two bishops of Mariannhill–Fleischer and Streit. The appointment of Bonaventure Dlamini, FFJ, as South Africa’s first black bishop on February 21, 1954 [19] heralded the beginning of the Africanisation of the episcopate in South Africa. At the time of his appointment, Dlamini was in charge of St. Magdalen Mission, formerly an outstation of Mariannhill. Interestingly, “Fr. Dlamini [who] was described as ‘a man of high moral standards and priestly conduct’ was a good man, gentle and kind but with no experience of business, of administration, or of handling difficult people. He was thrown into the deep end after his consecration as bishop and must sometimes have wondered why he ever accepted the post.”[20]

The consecration of Dlamini by the apostolic delegate, Archbishop Celestino Damiano, took place at Lourdes, the episcopal see of the new diocese, on April 26, 1954. He was assisted by Bishop Streit of Mariannhill and Bishop ‘Mabathoana of Leribe.[21] The Cathedral of Lourdes, one of the largest churches in Natal, was too small for this occasion, so an open-air altar was erected by the Technical College of Mariannhill and loudspeakers installed at Lourdes High School. The playground of the school accommodated the people who came for this occasion: “The consecration was attended by three archbishops and seventeen bishops and monsignori. One hundred priests were present who had come from as far as Cape Town, Basutoland, and Rhodesia.”[22]

Subsequent to his consecration, it became apparent that Dlamini was not supported by the Mariannhill Mission. As Oswin Magrath, the former rector of St. Peter’s Major Seminary at Pevensey and Hamanskraal could state: “They [Mariannhill] did not support Dlamini at all. At the background, there is still the fact that Mariannhill did not back him….so poor Dlamini had really a bad start. But he did his best.” [23]

Staffing the New Diocese

Dlamini’s first vicar general was John Baptist Sauter, who was also the secretary and procurator. Sauter was probably appointed because he founded the People’s Bank of Mariannhill, which proved to be successful. It followed the philosophy of the Catholic Action Union of Bernard Huss. Sauter later bought farms for the bank and sold them at a profit. He had a fair amount of good financial skills. Hermann Mennekes became one of Dlamini’s consultors, while Xavier Brunner became the parish priest at Lourdes. An able administrator of what was a very large mission, Brunner was later to fall into disfavor with the black priests in the diocese. Upon leaving the mission, he was replaced as parish priest by Mennekes. Subsequently, Mennekes also left, being replaced by Laurence Schleissinger.

During this time, Dlamini appealed for outside help. In response, a Redemptorist [24] priest, Fr. Wrangham, became vicar-general, while John Sauter withdrew to Jericho Mission. Centocow, although not initially included in the new Diocese of Umzimkulu, was later incorporated. As time went on, the priests from the Congregation of Mariannhill Missionaries were excluded totally from the administration of the Umzimkulu diocese.

The Umzimkulu Experience

At the time of Dlamini’s consecration, over fifty black diocesan priests had been ordained from St. Peter’s seminary. There were also black priests from the Franciscan Familiar of St. Joseph’s (FFJ) as well as the first, newly-ordained, Oblate priests [25], Dominic Khumalo and Jerome Mavundla. As was desired by Rome, black priests could have helped in the governing of the diocese. However, in order to overcome some initial difficulties, Dlamini appointed a white administrator, John Baptist Sauter, as his first vicar-general in the diocese.

Some of what transpired in the Umzimkulu diocese, leading to Dlamini’s early retirement, could be explained by Mariannhill’s withdrawal, by racism, and by Dlamini’s own inexperience. These explanations are colored by the popular, oral perceptions of priests and bishops, as well as the present author’s analysis.

The Withdrawal of Mariannhill

The Mariannhillers, also known as the Congregation of Mariannhill Missionaries (CMM), were not initially excluded from the administration in the new diocese. Instead, according to an interview with David Moetabele in 1997, they began “pulling out and they knew very well that if they pulled out everything would go to pieces because they were the pillars money-wise which was used to run the farms and the black priests were never trained to run these kinds of things.” [26]

For example, having bought the land at Lourdes Parish, the Trappists began to farm the area. People who wished to become Catholics joined the villages of the evangelized. They built schools and established settlements for Christians. But the bishop needed a person who knew how things were run and how to get resources. When Dlamini took over the diocese he did not know where to get the funds needed to run it. Most of the black priests were unskilled in matters of agriculture, administration, and financial management. Hence, as David Moetapele comments, “From the word go everything went to pieces.” [27]

When Mariannhill pulled out, the farms and other projects used in Umzimkulu Diocese to produce an abundance of agricultural products were left unattended. The bishop himself was seen buying groceries in Umzimkulu town because he could not delegate. [28]

A Question of Racism

Magrath attributes the failure of the diocese to segregation in the church, whereby the black priests were not treated as equals to the whites. Among the priests themselves, there were also some racial tensions. For example, the person in the position of apostolic delegate just before Dlamini’s appointment was apparently very autocratic. Having had problems with some black priests, he advised all the bishops to place all black priests as assistants under white priests. According to Magrath: “This was supposed to be confidential, but it came out. His name was Martin Lucas SVD, he was a powerful character. He used to tell bishops what to do. Dlamini was put under somebody.” [29]

Furthermore, once Dlamini was appointed there was an immediate outcry from the white Catholics at the inappropriateness of the appointment. As Stuart Bate expands:

The white Catholics of Margate protested most “vehemently against having a non-European as bishop of Europeans.” They could not conceive of how a black man could have charge of white people or indeed be part of their white church and so the campaign was started to “keep your church white.” Whilst the Margate Catholics are cited in the literature they should not be singled out as more racist than other whites of the time. Their actions reflected the common mentality within the settler community at large. [30]

An Inexperienced Administrator

When the CMM withdrew, the ripple effect was felt in most of the parishes in Umzimkulu. As Hermann says: “The well established missions of Lourdes and Centocow soon experienced total financial and economic ruin. Their administration and further development proved beyond the ability and strength of the new regime. It was natural that the Mariannhillers keenly felt the failure of this first attempt of indigenisation in their mission territory.”[31]

When it came to administering the diocese, Dlamini had tremendous problems. Possibly his training had not equipped him with the necessary skills. Nicholas Lamla believed that Dlamini was wrongly chosen; for him, the person who should have been consecrated bishop was Fidelis Ngobese. However, as Lamla states, Dlamini “was a pastor, a good preacher, a very devotional person, very sympathetic–I think that is about all. To be a bishop he was not one percent qualified.”[32]

This point is corroborated by interviews with some priests who allege when they were doing Canon Law at the seminary, the lecturers used to say, “We will skip this section on the parish priest and go to the section on assistant priests.”[33] It seems that most of the black priests might have been educated like this–in other words, to be assistant priests–and it was a giant leap from being an assistant priest to that of a bishop. This has been vigorously denied by the CMM priests who assert that the training was conducted fairly and the priests where trained to be future leaders in the Catholic Church in South Africa.

In accordance with the encyclicals Donum Fidei (1957), Maximum Illud (1919), and Rerum Ecclesiae (1926), the training of local clergy was to be thorough, complete and on a level with the white missionary clergy. Apparently, in Dlamini’s case, the training provided, especially in administration and finance, was highly questionable. One can deduce that the seminary did not provide adequate training for the priests who were supposed to be the future leaders of the church.

Archbishop Hurley noticed the poor administration when he worked at the seminary as an administrator. Serving there for seventeen years until a new bishop was appointed, he could not do much. After all, he was not the bishop of the area. As Hurley was archbishop of Durban and the apostolic administrator of Umzimkulu, he tried to regularize the finances in the diocese, make the records clear, file things correctly, find title deeds, and put them in their proper order. As he could later state: “I was not very creative; one does not do that normally as an apostolic administrator. Finally, they decided to choose Bishop Gerald Ndlovu and again he found it difficult, too!”[34]

Hurley goes on to say that one of the things that caused problems for Dlamini was that “He didn’t have the gift of administration. A bishop may be holy and prayerful but he has to be a good administrator and keep things in order. He had difficulties in this area but he was a nice man. While I was there I realized that there was a great shortage of priests there.”[35]

The Issues of Nepotism and Finances

According to Bishop Dominic Khumalo, when the CMM–who were the financial backbone of the diocese–pulled out, it was practically bankrupt. Dlamini just could not manage the funds. Nepotism was also clearly rife in the Diocese of Umzimkulu. David Moetapele saw that Dlamini was running the diocese as if it was his family–a state of affairs that was obviously to create problems.[36] The Diocese of Umzimkulu was never a success from the time it was formed. Lamla noted that the real person who brought him down was a man by the name of Benjamin Dlamini.

When Dlamini became bishop, Benjamin decided to leave the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) [37] and join the Umzimkulu Diocese because he was a “Dlamini.” This is how Benjamin became Dlamini’s assistant. It is important to note that Benjamin was not even a close relative to the bishop.[38] However, he was readily accepted as he was an educated, intelligent, talented, and capable man. As Brain notes “when they went overseas, they went together.”[39] The Diocese of Umzimkulu was similar to the Diocese of Leribe in that both were dependent on Western financial help in order to survive. Hence, the bishop and his assistant often travelled overseas to raise funds. Although he joined the diocese without a proper transfer, Dlamini made him a vicar-general, an appointment which was canonically incorrect. This led to local priests believing that the bishop was corrupt, that being a Dlamini, he looked after his own. Meanwhile, while at Umzimkulu, Benjamin flourished, owning a butcher’s shop, various stores, a farm, and a large poultry farm. [40]

At one time, Benjamin Dlamini was sent to Germany to raise funds but he had problems distinguishing between his money and that of the diocese. When Benjamin came back to South Africa, he had a beautiful Mercedes Benz and a tractor which he claimed were both gifts from friends in Germany. Dlamini could not accept this because he had sent Benjamin to fundraise for the diocese, not for his own personal gain [41]

So it seems that most of the personnel involved in the new diocese were not ready for their responsibilities and might have been pushed into jobs for which they were unqualified.

Dlamini’s Resignation

Soon after the CMM withdrew from the diocese, the well-established missions of Lourdes and Centocow experienced severe financial and economic problems. The new administrators soon proved incapable of handling and developing the huge mission. The situation was deteriorating at an alarming rate and this, in turn, affected the CMM.

Dlamini was in charge of the diocese for fourteen years. In 1968, due to the pressure of work and poor health, he resigned and became an auxiliary bishop of Mariannhill. After his resignation, he returned to Kwa St. Joseph Monastery, the Mother House, and helped in the diocese of Mariannhill. In the meantime, on January 8, 1968, Msgr. Peter Butelezi was appointed apostolic administrator of the Umzimkulu Diocese. He left four years later when he was consecrated auxiliary bishop of Johannesburg.

In the years that followed his resignation, Dlamini’s health steadily deteriorated until he was admitted to the Assisi Hospital, near Port Shepstone. He died September 13, 1981 and is buried among his FFJ members, at Kwa St. Joseph Cemetery at Emabheleni. [42]

On September 11, 1972, the archbishop of Durban, Denis Hurley, was appointed apostolic administrator of the diocese of Umzimkulu, his vicar being Aurelius Boschert from the Congregation of Mariannhill Missionaries (CMM). Hurley assisted the diocese until Bishop Sithunywa Ndlovu was consecrated in 1987. However due to the problems that already existed in the diocese, Bishop Ndlovu resigned in 1994, whereupon Archbishop Wilfred Napier took over the administration of the diocese. [43]

George Sombe Mukuka

Notes:

-

Joy Brain,* A New Beginning? The Umzimkulu Diocese Fifty Years Later*, (Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 2004), 54.

-

UmAfrika, (May 8, 1954).

-

Joy Brain, A New Beginning? The Umzimkulu Diocese Fifty Years Later, (Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 2004), 52.

-

“Ein Mischling wird Priester,” in Vergissmeinnicht, 63, (1945), 90; See also, Pallotines: Society of the Catholic Apostolate, 32-33. The FFJs were founded by the first bishop of Mariannhill–Fleischer in 1923. This congregation accommodated vocations from the African community.

-

Other colored priests were trained at St. Peter’s. The first two colored priests trained for the diocese of De Aar; Joseph J. Alacaster (1962) and Cecil J. Wienard (1962).

-

Walbert Bühlmann, The Missions on Trial. Addis Ababa 1980: A Moral for the Future from the Archives of Today, [Translated from the German by A. P. Dolan, Assisted by B. Krokosz], (Slough: St. Paul Publications, 1978), 83-85.

-

Bühlmann, The Missions on Trial, 49, 51.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 53-54.

-

See New Catholic Dictionary: “In 1882 Reverend Francis Pfanner, then prior of the Trappist (Reformed Cistercian) Monastery of Mariastern (Bosnia), volunteered to establish a monastery in Cape Colony, in order to try to adapt the rule of the order to the missionary life. He settled in a place he called Dunbrody in 1880, but was forced to abandon it in 1882, and transferred his community to Mariannhill, Natal. In 1885 Mariannhill was erected into an abbey, with Father Pfanner as first abbot. During the next few years Father Pfanner founded seven mission stations throughout Natal, to provide for the needs of the natives. Between 1894 and 1900 nine stations were established in Natal and Cape Colony, and two houses in German East Africa. Later a station was erected in Rhodesia, and two more in Natal. The Congregation of Regulars, in 1909, issued a decree separating Mariannhill from the order of Reformed Cistercians, forming of it the ‘Congregation of the Mariannhill Missionaries.’” (CMM), Web site http://saints.sqpn.com/ (accessed January 30, 2009).

-

Oswin Magrath, interview by author, July 19, 1996, Cedara, Pietermaritzburg, tape recording.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 55.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?,

-

Denis, Hurley, interview by author, July 28 1999, Cathedral, Durban, tape recording.

-

UmAfrika, (May 8, 1954).

-

Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 120.

-

Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 120.

-

Southern Cross, (December 29, 1937). There are no archives in the Diocese of Umzimkulu. Some of the personal correspondence, title deeds and financial papers were transferred to the archives of Mariannhill. These were eventually transferred to Rome at the Generalate of the CMM. However, with time, access will be gained to the numerous archival resources stored in Rome at SCPF.

-

UmAfrika, (March 13, 1954); See also, Sieber, “Religious life,” 69, 126, 127.

-

UmAfrika, (March 13, 1954; April 3, 1954; May 8, 1954; January 1, 1955); Southern Cross, (April, 1954); See also, Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 120.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 54.

-

UmAfrika, (May 8, 1954); See also, Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 120.

-

UmAfrika, (May 8, 1954).

-

Magrath, “Interview 1.”

-

The Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, commonly called Redemptorists and indicated by the Latin acronym “CSSR,” is a religious community of Catholic priests and brothers founded by Saint Alphonsus Liguori in Naples in 1732 to preach to the destitute.

-

The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) is a religious order of the Roman Catholic Church founded on January 25, 1816 by Saint Eugene de Mazenod, a French priest from Marseille. It was first recognized by Pope Leo XII on February 17, 1826. Originally established to revive the church after devastation by the French Revolution, the religious order now serves in various countries around the world. Though they originally focused on working with the poor, they became known as a missionary and teaching order as well. In 1938, Pope Pius XI called them “specialists in difficult missions.”

-

David Moetapele, interview by author, October 24, 1996, Pretoria, tape recording.

-

Moetapele, “Interview 1.”

-

Paul Mngoma, interview by author, January 13, 1999, Mariannhill, tape recording.

-

Magrath, “Interview 1.”

-

Stuart C. Bate, “The Church under Apartheid,” in The Catholic Church in Contemporary Southern Africa, Joy Brain and Philippe Denis, (Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1999), 153.

-

Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 120.

-

Nicholas Lamla, “Interview 1,” by George Mukuka, tape recording, Umtata, October 29, 1997.

-

Lamla, “Interview 1.”

-

See also, Brain, A New Beginning?, 61.

-

Hurley, “Interview 1.”

-

Moetapele, “Interview 1.”

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 60.

-

Khumalo, “Interview 1”; See also, Brain, A New Beginning?, 61-62.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 60.

-

Khumalo, “Interview 1.”

-

Khumalo, “Interview 1.”

-

Archives of the Vice-Province of St. Joseph, South Africa, “Bishop Bonaventure, Pius Dlamini’s Obituary,” 1.

-

Brain, A New Beginning?, 87-130.

Bibliography

Brain, Joy. A New Beginning? The Umzimkulu Diocese Fifty Years Later. Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 2004.

Brain, Joy, and Denis, Philippe (eds.) The Catholic Church in Contemporary Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications, 1999.

Bühlmann, Walbert. The Missions on Trial. Addis Ababa 1980: A Moral for the Future from the Archives of Today, [Translated from the German by A. P. Dolan, Assisted by B. Krokosz]. Slough: St. Paul Publications, 1978.

Hermann, Aldegisa Mary. History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill in the Province of Mariannhill, South Africa. Mariannhill: Mariannhill Mission Press, 1984.

Hurley, Denis. Interview by author, July 28, 1999, Cathedral, Durban. Tape Recording.

Khumalo, Dominic. Interview by author, March 25, 1998, Pietermaritzburg. Tape Recording.

Lamla, Nicholas. Interview by author, October 29, 1996, Cathedral, Umtata. Tape Recording.

Magrath, Oswin. Interview by author, July 19,1996, Cedara, Pietermaritzburg. Tape Recording.

Moetapele, David. Interview by author, October 24, 1996, Pretoria. Tape Recording.

Mngoma, Paul. Interview by author, January 13, 1999, Mariannhill. Tape Recording.

This article, received in 2009, was written by Dr. George Sombe Mukuka, a faculty research manager at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and 2008-2009 DACB Project Luke Fellow.

Photo Gallery

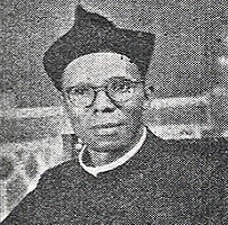

[1] Bishop Dlamini. Photo from UmAfrika (April 24, 1954), 1.

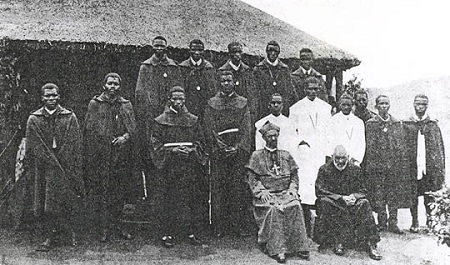

[2] Franciscan Familiars of St. Joseph’s, with Bishop Fleischer seated. Photo from UmAfrika (April 26, 1954), 5.

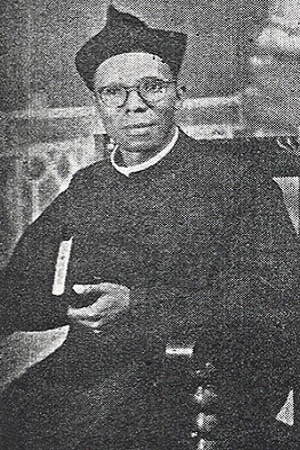

[3] Bishop Adelbero Fleischer. Photo from St. Mary’s Minor Seminary Archives, Mariathal, Ixopo.