Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Mncadi, Alois Majonga

Alois Majonga Mncadi was the second black Catholic priest in South Africa.

There is very little information in the archives of the Durban Archdiocese on the life of Mncadi. We know that he was born in 1877 but we have no information on his family, his childhood, or his upbringing.

Mncadi was sent to Rome on August 24, 1894, and was ordained in 1903. [1] The Catholic Directory records that in 1921 he worked at Maria Linden and, from 1925 to 1927 [2], at Mariannhill as well as at Lourdes, Centocow, Ixopo, St. Michael’s, Himmelberg, St. John’s, and Maria Trost. [3]

From 1903 to 1932, Mncadi worked as a priest at Mariannhill. He wanted to promote the local culture in dealing with issues in his ministry. Around 1918, while working with Father Florian Rauch, rector at Maria Trost Mission, Mncadi experienced difficulties. Their correspondence highlights the misunderstanding between Mncadi and Father Rauch. [4]

As an African used to a communal way of life, Mncadi wanted Christina, his brother’s daughter, to live with him, so that she could help him. Instead, under pressure from Rauch—who was trying to force Mncadi to live alone, following a Western individualistic lifestyle—she left the mission. As Mncadi stated, “she is asked to go now to Johannes Mncadi her father, by him [Rauch], but I am sorry that there is somebody interfering and provoking her to do so. So I tell you that according to the court and Zulu law she belongs to my family and besides my family she belongs to nobody. I was astonished to hear that your attitude is against the wishes of my family, while these being such are wishes of me too.” [5] He continued by saying that he was going to put the case before the court, stating that he was “going to protect the rights of my family and nobody can prevent me from doing so. Therefore, I give you a chance to get away from this trouble in which wrongly you involve yourself.” [6]

Rauch forwarded the letter to the abbot, commenting on “the style of the letter in which it is done, the pride and arrogance it contains.” [7] He explained what had happened, “Some time ago he [Mncadi] endeavored to get the girl to St. Michael in order to become his servant maid, but I [Rauch] persuaded her not to be willing, as other people would talk about it. I spoke to the abbot who was also against this…The principal reason, of course, why Father Aloys is so excited against me is because the girl refused to come to him; I admit that I influenced her to abstain from that and will again if necessary.” [8]

Rauch said that if the brother came to collect her, he would not have a problem but he would protest if, “Father Aloys should try again to make her his servant maid or chambermaid. The abbot is against this. I have also sent him a copy of the letter.” [9] No further documentation is available to show what finally transpired.

While working in the Mariannhill diocese, Mncadi also had some misunderstandings with Bishop Fleischer involving the ownership of a farm. In 1918, Mncadi bought a farm in the Umzimkulu area. He employed a farm manager to look after the affairs of the farm while he continued to work as a priest. His farm prospered to such an extent that he was soon able to pay off the mortgage on his farm with the profits he made selling agricultural products.

In 1922, Fleischer was elected bishop. Two years later, Bishop Fleischer wrote to Mncadi, stating that his ownership of the farm would lead to his disobedience and even possible eternal damnation. In an angry letter dated December 28, 1924, he ordered Mncadi to sell it forthwith and also suspended him from his priestly duties:

Under the 4th September this year I ordered you to dispose of your farm before Christmas, because the possession of your farm will one day became a great danger to you of not listening to your bishop and risking eternal damnation whilst you need no farm as the bishop will care for you paternally as long as you are his loyal priest. On 28th of November I reminded you of your duty, but you answered by two very irrelevant letters to say not more. At the same time you wrote a very bad letter to Father Julius [Mbhele] in which you try to undermine the authority of the bishop. I upon this suspend you from saying hl [holy] mass. Now today before me Father Superior and Father Julius Mbhele you declared that you did not try nor are willing to do so in the future, to dispose of your farm. I shall put your case before the apostolic delegate. [10]

In fact, the problem that arose with the farm was much more than a matter of ecclesiastical obedience. During the first decades of the twentieth century, as a result of the 1913 Land Act and several other pieces of colonial legislation, the people in the black middle class were systematically dispossessed of their property. The white colonial government wanted to own not only the land but also the means of production. In this matter, the (white) bishops—and in this case Bishop Fleischer—blindly followed the government’s discriminatory policies.

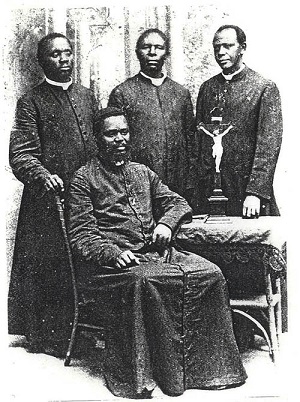

As a result of a campaign by Julius Mbhele amongst the black priests, Fr. Andreas Ngidi, the third black Catholic priest in South Africa , formulated a petition which was sent to the apostolic delegate in 1924. The priests petitioned for the right to continue owning farms. The three priests (Fr. Alois Mncadi, Fr. Julius Mbhele, and Fr. Andreas Ngidi) managed to arrange an interview with the apostolic delegate, Giljswijk. [11] During this interview the delegate stated among other things that, “even from the beginning to the end, that there was no question about your right in possessing the landed property [and] even your bishop did not…deny that you have that right.” [12] He went on by stating that although they “have freedom as far as the possession is concerned, but in regard to the exercise of your right upon it, the bishop might have to interfere with it, and rightly for certain he could and can transfer you from the place nearest to your farms to a far distance.” [13] Giljswijk glibly added that, suppose “the bishop sends you to Pondoland! How then could you exercise your rights in it?” [14]

In reply, the black priests assured Giljswijk that their farm managers could undertake all the work necessary and that it would not make any difference whether they lived nearby or were transferred far away! The delegate then went on to state that, “it would have been better if you had no farms; it does pain me much to see that you are only four native priests and you could not avoid the trouble with your bishop.” [15] Fr. Mncadi did not sell the farm and the bishop continuously had problems with this issue.

Shortly before leaving the Mariannhill vicariate, Mncadi worked at Highflats, before finally moving in 1933 to Zululand.

Mncadi’s Later Pastoral Work

In 1932, Mncadi applied to go to Inkamana, a Benedictine monastery located in Vryheid, Zululand . Concerning this, Bishop Spreiter wrote, “Rev. Alois wrote to me applying to come for some time to Inkamana. The answer I have sent is attached here with this letter. Of course I will help, but cannot if his bishop has not given consensus that is “conditio sine qua” and also that he can say mass.” [16]

Mncadi was allowed to go to Inkamana in 1933, although he was already sickly when he arrived. The Chronicle of Inkamana observed:

Father Mncadi was already sickly and weak when he came to us. Nevertheless, he worked hard from the day he arrived. He gave instruction, preached, heard confessions, and visited outstations on horseback. Nothing seemed too much for him. From about July, his health deteriorated alarmingly. The doctor diagnosed cancer. Father Alois had problems with his digestion; he lost weight. It was only with great effort that he could celebrate Mass…He left us on October 2 and died on October 28, suffering from cancer of the liver. [17]

The archival sources available on Mncadi are scanty. However, from the little that was found, we see how the second black Catholic priest in South Africa struggled with his day-to-day ministry. In the end he triumphed and died an early death. By the time of his death, he had been a priest for thirty of his fifty-nine years. [18]

George Sombe Mukuka

Notes:

-

UmAfrika, November 3, 1933, 3.

-

The Catholic Directory of South Africa, 1921–1925.

-

See Otto Heberling RMM, “Mariannhiller Rundfunk”: Neueste Missionsnachrichten,” Vergissmeinnicht 63, (1934), 38; see also, UmAfrika, November 3, 1933, 3.

-

Maria Trost Mission is a mission station near Port Shepstone, KwaZulu–Natal.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “Alois Mncadi, Letter to Father Florian, St. Michael’s,” June 25, 1918.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “Alois Mncadi, Letter to Father Florian, St. Michael’s,” June 25, 1918.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “Father Florian, Letter to Bishop Delalle,” Maria Trost Mission, July 2, 1918.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “Father Florian, Letter to Bishop Delalle,” Maria Trost Mission, July 2, 1918.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “Father Florian, Letter to Bishop Delalle,” Maria Trost Mission, July 2, 1918.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests, “True Copy of Bishop Fleischer Letter to Aloys Mncadi,” Mariannhill, December 28, 1924.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

12.Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi, Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi, Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana, October 13, 1932.

-

See Heberling, “Mariannhiller Rundfunk,” 38–40.

-

UmAfrika, November 10, 1933, 1.

Bibliography

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the first Black Priests.

The Catholic Directory of South Africa, 1921–1951. Pretoria : SACBC, 1952.

Heberling, Otto RMM, “Mariannhiller Rundfunk”: Neueste Missionsnachrichten,” Vergissmeinnicht 63, (1934), 38.

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1.

UmAfrika, November 3, 1933.

This article, received in 2009, was written by Dr. George Sombe Mukuka, a faculty research manager at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and 2008-2009 DACB Project Luke Fellow.

Photo Gallery

[1] Mncadi. Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1934), 39.

[2] Four first black priests: Ngidi, Mncadi, Mbhele, and Mnganga (seated). Photo from *Vergissmeinnicht *(1924), 251.

[3] Grave of Mncadi and Mnganga. Photo from George Mukuka photo collection, 1997.