Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Mnganga, Edward Müller Kece

Edward Müller Kece Mnganga was the first black Catholic priest in South Africa.

Edward Müller Kece Mnganga was the first black Catholic priest in South Africa.

In November 1887, “a promising boy” by the name of Edward Mnganga from the Latin School at Mariannhill presented himself to Father Franz Pfanner, the Prior of Mariannhill Monastery, who subsequently decided to send him to Rome to study for the priesthood. [2]

Mnganga originally came from Mangangeni in Mhlatuzane. [3] As Mrs. Malukati Mncadi recalled, “The thing he used to tell me was that he was coming from Mangangeni…as he [Edward Mnganga] was called Mangangeni. I think that place is close to Mariannhill.” [4] Mnganga travelled to Rome with a young Mariannhill priest from England by the name of David Bryant. [5] Bryant had been ordained that same year and, after his return to South Africa, had worked in the Transkei, as it was then known, later being transferred to Ebuhleni, near Emoyeni.

Ebuhleni had been founded as a result of a series of events closely associated with the white Zulu chief, John Dunn. Although Bishop Jolivet had despaired over whether a mission in Zululand would be possible, an ideal opportunity arose when Dunn-who realized that his life was coming to an end-met with the resident British commissioner, Marshall Clarke, to discuss possible ways of securing a good future for his offspring. [6] Dunn had forty wives and over one hundred children of mixed race. As it happened, Bishop Jolivet and Clarke were good friends, having been prisoners of war together during the first Transvaal War of Independence; their relationship continued when Clarke was made resident commissioner in Basutoland. [7] As a result of Dunn’s overtures, and with the vicarial bursar William P. Murray acting as go-between, an agreement was reached and Catholic missionaries were sent to Dunn’s farm at Emoyeni, just outside Eshowe, Zululand. The aim of this mission was:

To provide for the education of the children of the late John Dunn. Dunn’s chief wife Nontombi was willing to provide a schoolroom and quarters for the teachers. The official application to open the mission was made by Murray and approved by Clarke. Father Anselme Rousset, Brother Boudon, and three Dominican sisters from Oakford set out in February 1896 to begin the new venture. The party was accompanied by Father Mathieu, the most experienced among the Oblates missionaries to the Zulus, who assisted with the luggage and with the setting up of the mission itself. [8]

After establishing themselves, the missionaries built a school at Emoyeni, close to Dunn’s homestead. In June 1896, Anselme Rousset applied for land at nearby Entabeni Hill for the purpose of cultivation. Later, he established the Holy Cross Mission there, a facility that catered to the Zulu peoples in the area. On his first visit to the station in December 1898, the bishop confirmed the presence of “about thirty neophytes, most of them being of the Dunn family.” [9] With these new converts and a number of white children who had been accepted at the school, the mission was set to grow.

In the meantime, Bryant [10] was moved in October 1896 from the Transkei to Zululand. He stayed a short time at Emoyeni, during which time he negotiated for a further mission site and was given ten acres of land at Ongaye Hill, Ebuhleni. He subsequently wrote:

After I had spent a few months there [Emoyeni], roaming the Zulu country looking for a suitable site for my first native mission (R.C.) among the Zulu, I at length struck upon one of the loveliest spots in all South Africa, and I immediately named it Ebuhleni. Situated just below the oNghoye all-range (with its great forest, ten miles long by two through), the country was an extensive expanse of hundreds of gentle hills, all of various shapes and heights, and all covered with beautiful woodlands, and having numerous crystal brooklets running along the valley. The whole place was furthermore thickly covered with Kraals, all heathen, there being not a single “town native” anywhere around. [11]

A chapel and hut were built for Bryant who held a well-attended service after Christmas in 1898. It was in this same year that Mnganga returned to South Africa after successfully completing his studies at the Collegium Urbanum in Rome. [12] The Collegium Urbanum had been established in 1627 by the bull Immortalis Dei and placed under the direction of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. Its main purpose was to train candidates from around the world for the diocesan priesthood. These priests, if commanded by the pope, would then promote or defend the faith anywhere in the world, even at the risk of losing their lives. Urban VIII (1568-1644) [13] realized that it was necessary to establish a central seminary for missions where young ecclesiastics could be educated, not only for countries with no national colleges, but even for those endowed with such institutions. He thought it desirable to have in every country priests educated at an international college where they could get to know each other and thereby establish important relationships for the future.

An example of how Urban VIII’s vision of ideal future relationships could work in real terms is captured in an extract from a letter to Mnganga by one of his former classmates at Urbanum: “I have the honor to enclose a small alms for the Zululand Mission. I was a student some thirty years ago in Rome with a Zulu priest. I think his name was Müller. May I ask a kind prayer, as my health is very poor.” [14]

Upon Mnganga’s arrival, “Bishop Jolivet decided that he would be of most use to the vicariate among his own people in Zululand and sent him there to assist A. T. Bryant (later known as David), who was working amidst the Zulu at Ebuhleni.” [15] We learn afterwards that:

After April 1898 Bryant was assisted by the first Zulu priest, Father Edward Mnganga (Kece) who was to take charge of the school. Father Mnganga, who had left for Rome in 1887, was a [diocesan] priest who had his early education at Mariannhill and was to spend most of his life in the Black missions. Once the school was on its feet and a reasonable number of pupils attending each day, two Dominican sisters were brought from Newcastle to undertake the teaching; and when the number of pupils reached thirty Bryant applied for a government grant. [16]

By 1898, the Emoyeni Mission was serving about eighty Christians and catechumens while, at Ebuhleni, Bryant had two hundred people attending his Sunday services.

Mnganga’s Early Work in the Diocese of Mariannhill 1898-1906

Mnganga worked at this mission from 1898 to 1906. While there, he encountered many problems. [17] In particular, there was a violent clash between Mnganga and Bryant when the latter provoked Mnganga, who then became angry, lost his temper, and threatened Bryant. Consequently, Bryant, probably with the assistance of some white missionaries and in collaboration with the civil white authorities of the time, placed Mnganga in a government asylum in Pietermaritzburg for seventeen years, under the pretext that he was mentally deranged.

In his Vergissmeinnicht article, Vitalis Fux outlined the main reasons for Mnganga’s difficulties:

The difficulties he faced as a priest were white racism, human faults, passion, and jealousy. These dangers grew so much that it managed to destroy his soul. His ideas of a priest and holy faith on one side and the difficulties from the outside and a cruel reality on the other side fought a dangerous battle against his existence… He had to go all this way, till the height of Calvary in deep darkness. He no longer worked as a priest. Instead, he had to stay in a mental institution for seventeen years… He, nevertheless, fought a good battle and still believed in God. [18]

It is important to note that “white racism, human faults, passion, and jealousy” [19] are considered to be the key difficulties that Mnganga faced. The main problem that is not addressed in Fux’s article is that Mnganga clashed with Bryant and, in his anger, resorted to physical violence. In oral testimonies, Mnganga’s anger is explained in four different ways.

First, according to Bishop Biyase, Bishop Khumalo, and Mr. Myeza, [20] Mnganga lost his temper because he was annoyed with Bryant [21] for ill-treating him because he was black. [22] Bishop Biyase (d. 2004), was the bishop of Eshowe Diocese (consecrated in 1975); he went to St. Peter’s Seminary and was ordained in 1960. He had never met Mnganga but heard stories from black priests during and after his seminary training. He attributes the clash to a misunderstanding between Mnganga and Bryant. [23] In trying to unravel this story Bishop Biyase explained:

Some simply say [Mnganga] had some kind of psychological sickness. It is not true. The people who lived with him at that time, they know the whole story. There wasn’t a good understanding between the two-the white priest [David Bryant] and Mnganga. It was here in my diocese… They had their ups and downs. And at one time Mnganga was so angry he lost his temper and almost killed this white priest. He lost his temper! This priest ran to the police and said Mnganga was mad! At that time, if a white man said such a thing about a black man, it was gospel truth! So the police never asked any questions, they went to the mission, took Mnganga to Pietermaritzburg as a mad man into the government asylum. [He] stay[ed] there [for] seventeen years. [24]

This interview clear states that the reason given for Mnganga’s arrest was because he was angry with the white priest. This story, according to the interviewee, seems to have been well-known by the people (other priests and parishioners) who were living with Mnganga. To prove the fact that Mnganga was not mentally disturbed, Bishop Biyase concluded by saying:

At the end they discovered that… he was very much sane, it would seem. He too, was already disillusioned and angry about it. He had said that “I will never go out of this asylum [Natal Government Asylum, Pietermaritzburg], until the man who brought me here comes.” Seemingly the man was not prepared, that is why he stayed there for so long. They pleaded with him to come out and he certainly came out. It is said, when he came out, he had forgotten how to say mass. [25]

With the help of Jerome Lussy, a Mariannhill priest from the monastery, Mnganga was released in 1922, staying for some time at Mariathal and beginning pastoral work there. [26] Another interviewee, Bishop Khumalo, [27] on the other hand, saw the deep sorrow and embarrassment embedded in the story when he recounted it. He said that the priest who had been in charge of Greytown and the surrounding areas, told them the “story of Mnganga, which was a very sad story, that he was accused of being mad and whether he went first to the mad-house, I don’t know. Both things happened to him. He was detained here as a mental case and also appeared in court against the accusations of the priest.” [28]

Bishop Khumalo also attributes the misunderstanding to Mnganga’s anger:

He seems to have hit him. He was tired of the insults he was getting from him, I think. Mnganga, evidently, was a big, tall man. I never met him. He was brought to Greytown court, to stand his case. The magistrate, who was chairing that case, told the priest who was at Inchanga with us what happened. He said, “Father, I have always had great respect for the Roman Catholic Church because they always accepted anybody who has been ordained as a child of God. I was very unhappy when I saw a very unchristian gesture given to Father Edward Mnganga, who was accused of having assaulted a white priest.” He stood for him and defended his case. [29]

Bishop Khumalo continued to state that when Mnganga spoke, even the magistrate felt ashamed to try his case, realizing that he was a far more educated man than he was himself. He concluded by saying that “this is the only story I know of those first four priests.” [30]

Mr. Reginald Myeza was born in Amanzimtoti in 1932. While he was growing up, his parish priest was Father Bonaventure Dlamini, later made bishop of Umzimkulu in 1954. Myeza went to school at Mariathal Mission. As he recalled:

I went to school in Mariathal from 1950 to 1953 before I was expelled. I do not know why I was expelled. I was the head prefect. The priest in charge did not know why my name was on the list there because I was not there. I subsequently went to Adams College. In 1959 I had to leave the country for Lesotho because the special branch was following me. [31]

Myeza joined the teachers training college run by the Sacred Heart brothers in Lesotho and later taught there. He then went to England, returning in 1980. With regard to the experiences of Mnganga he went on to state that:

People used to say that Mnganga should be canonized as a saint. The stories that we were told were that during mass, Father Mnganga having forgotten the key to the tabernacle, it would open on its own. Then there were some other miracles which were associated with this priest. There was so much talk about him being a saintly person. Mnganga was not mentally disturbed; we were told that it was persecution by the missionary priests-the same kind of persecution which Benedict Wallet Vilakazi experienced. When Mnganga was working in Zululand he physically assaulted Father Bryant-wamshaya bambizela amaphoyisa (“Mnganga physically assaulted Bryant who later called the police and he was arrested”). [32]

Second, Natalis Mjoli, a diocesan priest in the Eshowe diocese, believes that Mnganga’s anger flared because Bryant unnecessarily interfered with his school. Mjoli stated that “they [the priests and parishioners] used to tell us stories that happened to Mnganga, after he returned. He worked in the diocese of Natal at Ebuhleni parish, under Bryant. We happened to know these stories, because of what happened to him. I do not know whether I should tell you what actually happened.” [33]

For Mjoli, it was a well-known fact that the so-called natives had never been accepted in the church as full-fledged Catholic ministers. They were subjected to perpetual subservience towards whites. Mnganga knew African culture and the African way of life better than Bryant. He was sent to Ebuhleni to assist Bryant, who allotted him the outstations and the boarding school. Consequently, Mnganga became the tutor of the students and attended to the outstations.

Apparently, Mnganga was successful, in the sense that he had many students, much to Bryant’s dislike. Mjoli emphasized, “I still have few people to testify to the fact that when Mnganga had to go out to the stations which extended as far away as Nongoma on horseback, he had to be away for two or three weeks. Whenever he returned from the outstations, some of his best students had been expelled by Bryant for no apparent reason. Mnganga took exception to this, because he could not understand.” [34]

If the students had misbehaved, Mnganga thought Bryant should wait for him so that they could decide the issue together. When he inquired, he was not given an answer; “he was also neglected as to his status, after all, he was nothing.” [35] This went on for some time, until Mnganga’s temper flared up.

I understand he went to him and wanted to physically assault him. Father Bryant sneaking through the back door, had his horse carriage harnessed and drove up to Umtunzini and enlisted the assistance of the police and the magistrate, maintaining that Father Mnganga was mad, wanted to assault him for no reason and was breaking windows and doors! He wanted the magistrate and the police to come and arrest Father Mnganga. So they came, and after much humiliation and assault at Umtunzini he was transferred to Pietermaritzburg as a mad man where he stayed for seventeen years. [36]

According to Mjoli, the main reason for the disagreement was anger, but in this testimony, a reason lays behind his anger. The black priest was treated unfairly because he was successful in his mission work and because he was black. Interestingly, the above interviewee emphasized that there were people who could attest to these facts. As proof that Mnganga was sane, Mjoli concluded by stating that:

When the mental institution officially recognized that Mnganga was not mad they referred the matter back to the diocese requesting that they collect Father Mnganga… Father Mnganga adamant, wanted the bishop of Durban and Father Bryant to collect him… He wanted the people who had committed him to the asylum…to come and declare that he was sane. Since they failed to do this, he stayed there. When he eventually came out he was then assigned to a mission station in the diocese of Mariannhill, later to Mariathal where I met him. I could have learned much from him. I am sorry to say that, the people who knew much, Moseia, are now late. [37]

Other explanations for Mnganga’s anger can be found in the testimony by anonymous interviewees who described how Bryant burned and buried Mnganga’s vestments and how Mnganga found Bryant pointing to the private parts of a naked Zulu woman while studying Zulu ethnography. [38]

Another interesting explanation is given by the cousin of Alois Mncadi, Mrs. Malukati Mncadi (b. 1894), who later became a cook for Mnganga. Mrs. Malukati Mncadi observed that the clash came about because Mnganga was very intelligent, rather than because he was insane. “On his arrival from abroad…he stayed, then he was put into custody ‘…osibhinca makhasane’ (police…they arrested him). It was said that he was insane. But he had much intelligence to the extent that he looked insane.” [39]

Even though the causes of Mnganga’s anger are explained differently, all the testimonies concur in saying that Mnganga was somehow provoked to react in the way he did and that he was not “mentally disturbed.”

The Natal Government Asylum (NGA)

The Natal Government Asylum, which opened in February 1880, was not the first so-called psychiatric health facility in southern Africa. Robben Island had its own facility from 1840 on [40] and the “mental asylum” in Grahamstown was opened in 1875. Prior to this, those considered insane or mentally ill were housed in jails and hospitals in the colony.

The Natal Custody of Lunatics Law (Act No. 1, of 1868) gave colonial medical and legal practitioners the authority to define and detain those considered mentally insane or suffering from psychotic disorders. Medical certificates were issued when a person entered and exited the asylum. [41] Section 1 of the Law stated that, if a person was discovered to be insane, and circumstances denoted that he was insane, or if a person had committed a crime for which s/he could not be formally charged due to the circumstances of the crime, the resident magistrate could call upon two medical practitioners to help him. If they were convinced that the person was a “dangerous lunatic” or a “dangerous idiot,” [42] the magistrate would then issue a warrant, so that the person could be committed to a jail or public hospital. For such a patient to be released, permission had to be granted by the Supreme Court judge, or else the lieutenant governor could affect a transfer to a lunatic asylum, such as the Natal Government Asylum. At the time that Mnganga was committed there, the facility was headed by Dr. James Hyslop, an important figure in Natal medical circles. [43] Hyslop was appointed medical superintendent of the Natal Government Asylum in 1882, and remained in this position until he retired in 1914.

There is very little available clinical information on the patients. Until 1904, Hyslop and his deputies entered the clinical information in large leather-bound books, known as “case books.” The case book system was in accordance the British Lunacy Act of 1853, and there were separate books for “Europeans,” “Natives,” and “Indians.” These books, however, offer very little information about the patients because of the limited amount of space they provided for doctors’ observations. Up until 1980, several original case books were still kept at Town Hill Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, as the asylum is now called. Today, however, only the European case books remain, hence any attempts to try to establish Mnganga’s clinical history at the asylum is almost impossible due to the lack of sources. It appears that some of these books may have been deliberately destroyed or stolen from the hospital. [44]

Mnganga went to the Natal Government Asylum after 1906. From the statistics of the asylum, two preachers were admitted there during the year ending December 31, 1900. In the period between 1895 and 1909, six male patients-classified as clergymen, missionaries, and preachers-were admitted. [45] Unfortunately, the source does not give us their names; however, it is quite possible that Mnganga was one of these.

From February 1, 1911, Mnganga was treated as a “free patient” and thus did not have to pay for his medical treatment. A letter to this effect was sent by Dr. James Hyslop. In part, it reads:

I duly received your letter of the 18th ultimo which was submitted for the consideration of the government, and I have now pleasure in informing you that under the circumstances disclosed by you the secretary for the interior approves of the native priest Rev. Father Müller being treated as a free patient in this institution, from the 1st of the current month. [46]

Mnganga’s Release from NGA and Later Pastoral Work

In 1922, Jerome Lussy, a Mariannhill priest residing at the monastery, negotiated Mnganga’s release. Thereafter, Mnganga went to Mariathal and worked as an assistant priest. [47] From the year of his release, Mnganga was actively involved in the mission station at Mariathal. Later, he started a catechetical school at the same mission. He was also interested in writing books and articles and fostering black vocations, right up until the time of his death on April 7, 1945. [48] Mrs. Malukati said that the community in Mariathal “felt bad and felt good. But to Father Edward it was not so bad to me. Only his death was miserable, because…immediately after he became ill…because he was around here at Mariathal…he became ill then…he was taken to Sanatoli. We were willing to go to Sanatoli to pay a visit, but we were refused….Our hearts tended to be very sad then.” [49]

The Catholic Directory records that he worked at Centocow Mission from 1921 to 1924 and at St. Joseph’s Ratschitz Mission, Waschbank, today referred to as Wasbank, Natal, from 1925 to 1928 [50] as assistant priest. [51] In 1929, he was transferred to Maria Stella in Port Shepstone at Bishop Fleischer’s request:

I am in very great need of a priest at Maria Stella. I have called off Father Edward to St. Joseph’s as there was always only one priest at that Station St. Joseph. Father Boniface there can easily proceed alone, I think I have however told Father Edward, if he would not like to come to my vicariate and you would agree to incardinate [receive a priest from another diocese] him. I, from my part, would make no difficulties to incardinate him. I have written my letter to Father Edward by post. [52]

The Catechetical School at Mariathal, Ixopo

When Mnganga moved to Mariathal, Ixopo, in 1922 he initiated and ran the catechetical school with the support of Bishop A. M. Fleischer, CMM. This is evident from the following letter:

His Lordship Bishop A. M. Fleischer passed here yesterday and I presented the case to him who agreed that I could close the catechist school for winter holiday and reopen it week earlier. Thus I shall do so on the 18th inst. as to be ready for the journey the following day. Moreover, I would like to beg your Lordship to spend this holiday at your vicariate. Kindly inform the two native priests that I am coming. [53]

The school kept him busy most of the year: “Again I shall be giving lessons at the time to the catechist students who are five in all this term. Moreover I heard rumor that the Natal Vicariate intends to start her own catechist school, thus we hope their undertaking will be blessed with success.” [54]

Mnganga tried to secure the future of the catechetical school by providing some scholarships for future catechists in his will. He established “… a fund for bursaries to scholars of the catechists’ school of the Mariannhill Vicariate.” [55]

His Zeal for Indigenous Vocations

Mnganga’s invaluable contribution to the encouragement of local vocations is seen in the letter of Bishop Fleischer to the abbot which states:

Please send Father Edward word that he can go. He states that he is waiting for that. I need him really badly. Our native brothers stay [still] more than a year above with Brother Gerald, two-and-a-half hours outside Oetting [Highflats]. Now I have at last appointed Father Odo in charge of them, immediately after Christmas and he is eagerly waiting at Maria Stella to go there but first must Father Edward replace him. Should you intend to incardinate him and would Father Edward agree, I certainly will make no difficulties. But that could be settled, while he stays at Maria Stella. So please don’t delay longer but tell him that he might proceed immediately to Maria Stella. In June next year there are again several ordinations and it will become easier. [56]

And also in Mnganga’s own letter to Bishop Thomas Sprieter:

It is a great consolation for all native people to hear that Rome is in great favor of native religious movements and that your Lordship has already succeeded to have at least three candidates for clothing. Great pity that I am so far away from Inkamana else I would have liked to be present, again I shall be giving lessons at the time to the catechist students who are five in all this term. [57]

Mnganga also wrote several books, one of them entitled Isiguqulo sama Protestanti siteka kanjani namazwe amaningi (How the Theme of Protestantism is Perceived by Other Nations). [58] He was also heavily involved in preaching. [59] This shows that he functioned as a normal priest and excelled at most of his duties. He also supported indigenous vocations until his death. For example, in the will he made before he died in June 1938, he left a large sum of money amounting to £1,063-9-8 ($140,000) for the fostering of vocations among the natives:

I devise and bequeath all my estate and effects, real and personal, which I may die possessed of or entitled to absolutely unto the following: ecclesiastical vestments, chalice (if any) books and similar things to poor mission stations of the Mariannhill Vicariate; clothing to be given to poor natives, especially to relatives; money to be given to the native seminary and native familiars of St. Joseph and especially to the native congregation of St. Francis of Assisi, all of them in the Vicariate Apostolic of Mariannhill. [60]

George Sombe Mukuka

Notes:

-

As most of the missionaries could not pronounce his surname Mnganga, when in Rome he adopted the surname Müller. In some archival sources this name is sometimes used. The name Kece is a Zulu clan name for Mnganga.

-

Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle 1882-1895, 50. See also Respondek, “Die Erziehung von Eingeborenen zum Priestertum,” 45-55; Aldegisa M. Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill in the Province of Mariannhill, South Africa. (Mariannhill: Mariannhill, 1982), 19.

-

Vitalis Fux, “Der erste Priester aus dem Stamme der Zulus,” Vergissmeinnicht 63 (1945); Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle, 235-238. In describing the first Zulu priest to be ordained, the writer noted the astonishment and joy of especially the girl-children when Franz Pfanner, the Prior of Mariannhill, arrived with the priest at the mission school in Pinetown. Müller had been a pupil of the Mariannhill mission school since 1884 and had been sent to Rome in 1887 by Pfanner. Izindaba Zabantu, September 7, 1928; See also, Respondek “Erziehung von Eingeborenen zum Priestertum,” 48.

-

Malukati Mncadi, interview by author, September 1994, Mariathal, Ixopo, tape recording.

-

Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle, 50.

-

Alfred Thomas Bryant (also known as David Bryant after he joined the Trappist missionaries) describes the coming of the Trappist missionaries to Dunn’s household as follows: “When Dunn had died, the Res. Com. of Zululand requested our authorities in Durban to send up a missionary to advise and instruct the very large family now left stranded, with a considerable amount of property of all sorts-a tin-box full of golden sovereigns (as his principal wife Nontombi told me; and which, she said, had mysteriously ‘disappeared’ after his death, and was never found), thousands of cattle dispersed among hundreds of native kraals (nobody knew which!). And so on. Well, this missionary had already arrived at Emoyeni a few weeks before myself, and had already started his ‘half-cast’ mission there among his flock.” Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “David Bryant, ‘Some Sweet Memories’,” manuscript, 1947.

-

Joy B. Brain, “Early History of the Roman Catholic Church 1846-1885” (M.A. thesis, University of South Africa, 1974), 245.

-

Joy B. Brain, Catholic Beginnings in Natal and Beyond (Durban : T. W. Griggs, 1975), 118.

-

Brain, Catholic Beginnings in Natal and Beyond, 119.

-

Alfred Thomas Bryant was a Zulu ethnographer. Fashionable in academic circles, he collected oral traditions in Natal and published a book in 1929 entitled, Olden Times in Zululand and Natal Containing Earlier Political History of the Eastern-Nguni Clans, (Durban: Struik, 1965). He also published other works on the Zulu peoples, including A Zulu-English Dictionary (Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 1905); “The Zulu Cult of the Dead,” Man 17 (September 1917), 140-145; The Zulu People As They Were Before The White Man Came, (Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1949). See also Respondek, “Erziehung von Eingeborenen zum Priestertum,” 47. Interestingly, Bryant heard of Zululand during the 1879 war and describes it thus: “Suddenly I came to hear, for the first time, of ‘Zululand.’ The Graphic and London News were filled with pictures of ferocious savages, decked out in flowing plumes and heathen girdles, rushing wildly down, with assegais and up-raised shields, upon (apparently) quite fearless British squares. Poor deluded things! The assegais and flowing feathers always got the worst of it. That was the Zulu War of 1879.” Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “David Bryant, ‘Some Sweet Memories’,” manuscript, 1947.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “David Bryant, ‘Some Sweet Memories’,” manuscript, 1947.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238.

-

Maffeo Barberini was born in Florence in April 1568; elected pope, August 6, 1623; and died in Rome, July 29, 1644.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, file on the first black Catholic priests, “Rt. Rev. Mgr. Hook, A Letter to the Bishop for Mnganga,” The Presbytery, Queen’s Road, Aberystwyth, Wales, England, September 5, 1923.

-

Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle 1896-1911, 111. See also, Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 19; Brain, Catholics in Natal II, 252; Respondek, “Erziehung von Eingeborenen zum Priestertum,” 47-49.

-

Brain, Catholics in Natal II, 120. See also Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238. Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Izindaba Zabantu, September 7, 1928, where it says that soon after his arrival Mnganga was speaking Latin, English, Italian, German, and Greek as if they were his mother tongues. In 1928, he contributed two articles to the Izindaba Zabantu newspaper: “Umlando we Bandla” (History of the church) and “Nohambo lwabangcwele” (The way of the saints).

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 237.

-

Idem.

-

Reginald Myeza, interview by author, April 17, 2007, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, tape recording.

-

It is interesting to note that Bryant was a Zulu ethnographer. He was well known academically and popularized the term “Nguni” to refer to Zulu- and Xhosa-speaking people following the publication of his book. This has great impact on the story in the sense that Bryant was supposed to know Zulus better than Zulus themselves. Yet, when he encountered Mnganga (a real Zulu) he could not handle the situation.

-

The present author chose to interview two bishops because they are the only ones who both knew something about Mnganga’s life and also were willing to be interviewed. The other priests were selected randomly, especially those who had met or heard something about Mnganga. The first two versions of Mnganga’s problem with Bryant have been explained to the present author through oral testimonies by a lay person, black bishops, and priests who were ordained between the 1940s and the 1970s, Bishop Biyase, Bishop Khumalo, and Father Natalis Mjoli. These testimonies all concur: Mnganga, who was not on good terms with his rector, became angry and lost his temper. While the consequences of this anger are explained in different ways, it is important to understand that anger is the common denominator.

-

The sources he referred to in the interview are from the two books, one by Joy Brain and the other by Godfrey Sieber.

-

Mansuet Biyase, interview by author, April 22, 1997, Eshowe, tape recording; see also, Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238; see also, Biyase, interview.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 237. The problem with Biyase’s story is that he relied too much on information garnered from books and thus reconstructed some of his narrative. He nevertheless managed to complement this with information gained from other black priests.

-

Dominic Khumalo was auxiliary Bishop of Durban. Ordained in 1946 as one of the first Zulu Oblates, he was consecrated bishop in 1978 and died in 2005. Bishop Khumalo is the only source who mentions details of a court case. The other sources mention “anger,” “physical assault,” and the “mental asylum” as general themes. It is quite plausible that there was a court case as Bishop Khumalo recounted; further archival research needs to be done on court cases of Natal at the beginning of the last century.

-

Bishop Dominic Khumalo, interview by author, March 25, 1997, Pietermaritzburg, tape recording.

-

Khumalo interview.

-

Khumalo interview.

-

Myeza interview.

-

Myeza Interview.

-

Father Natalis Mjoli, interview by author, October 22, 1997, Empangeni, tape recording.

-

Mjoli, interview.

-

Mjoli interview.

-

Mjoli interview.

-

Mjoli interview.

-

These reasons were given by four priests who requested that their names not be disclosed. These four young Zulu priests, who were ordained in the late 1980s and early 1990s, spoke to me on condition of anonymity.

-

Mncadi interview.

-

Harriet Deacon, “The Medical Institutions on Robben Island 1846-1931,” in The Island: A History of Robben Island, 1488-1990, ed. Harriet Deacon, (Cape Town and Johannesburg: Mayibuye Books and David Philip, 1996), 57-75.

-

See Julie Parle, States of Mind: Searching for Mental Health in Natal and Zululand, 1868-1918, (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007); see also, Julie Parle, “States of Mind: Mental Illness and a Quest for Mental Health in Natal and Zululand, 1868 to 1918,” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2004),107-174; Julie Parle, “The Fools on the Hill: The Natal Government Asylum and the Institutionalisation of Insanity in Colonial Natal,” (paper presented at the Africa and History Seminar Series, University of Natal, Durban, March 17, 1999), 11.

-

Parle, “States of Mind,” 107-174.

-

Parle, “The Fools on the Hill,” 12.

-

Parle, “The Fools on the Hill,” 16-17.

-

See Parle, “States of Mind,” 107-174.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives: File on the first Black Clergy, “Medical Superintendent of Natal Government Asylum, Letter to Rev. Father A Chauvin, Roman Catholic Mission,” Pietermaritzburg, February 8, 1911. The letter is ambiguous in that it could have meant that he was going to receive free medication, or that he was going to be free within the confines of the asylum to do whatever he wanted, or that he was free to leave the mental institution. More archival research needs to be done on the nature of Müller being treated as a free patient. Interestingly, the oral sources state that he stayed there for a period of seventeen years, which means that since he was arrested in 1906, he only came out in 1922. Reliable sources about Mnganga in this period, however, are scarce.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238.

-

Fux, “Der erste Priester,” 235-238.

-

Mncadi interview.

-

The Catholic Directory of South Africa, 1921-1951 (Pretoria: SACBC, 1952); see also in Izindaba Zabantu, September 7, 1928.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, “Father Ballweg, Letter to the Bishop,” May 26, 1927.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, “A. M. Fleischer, Letter to a Bishop,” January 3, 1929.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “E. Mnganga, Letter Addressed to Bishop Spreiter OSB,” May 4, 1932.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “E. Mnganga, “Letter Addressed to Bishop Spreiter OSB,” January 30, 1934.

-

Natal Archives, Pietermaritzburg: 4/1/2/3, 2/4/2/2/45, “Native Affairs. Native Estates: Estate: Mnganga, Edward Müller,” Last will, June 15, 1938.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Black Clergy File #1, “R. M. Fleischer, A Letter addressed to ‘My dear Lord’,” Mariannhill, January 27, 1929.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Black Clergy File #1, “Rev. Edward, A letter addressed to ‘My Lord’,” Mariathal Mission, 30 January 1934. He also wrote several books, one of which was entitled, Isiguqulo sama Protestanti siteka kanjani namazwe amaningi (How the Theme of Protestantism is Perceived by Other Nations); see also UmAfrika, August 16, 1929. He was heavily involved in preaching; see UmAfrika, “Intshumayelo,” [Preaching] January 2, 1931.

-

UmAfrika, August 16, 1929.

-

See UmAfrika, “Intshumayelo,” January 2, 1931.

-

Natal Archives, Pietermaritzburg: 4/1/2/3, 2/4/2/2/45, “Native Affairs. Native Estates: Estate: Mnganga, Edward Müller,” Last will, June 15, 1938.

Bibliography

Brain, Joy B. “Early History of the Roman Catholic Church 1846-1885.” M.A. thesis, University of South Africa, 1974.

Bryant, Alfred Thomas. “The Zulu Cult of the Dead,” Man 17 (September 1917), 140-145.

——–. A Zulu-English Dictionary. Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 1905.

——–. Olden Times in Zululand and Natal Containing Earlier Political History of the Eastern-Nguni Clans. Durban: Struik, 1965.

——–. The Zulu People As They Were Before The White Man Came. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1949.

Bryant, David. “Some Sweet Memories,” (manuscript, 1947). Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid.

The Catholic Directory of South Africa, 1921-1951. Pretoria: SACBC, 1952.

Deacon, Harriet. “The Medical Institutions on Robben Island 1846-1931.” In The Island: A History of Robben Island, 1488-1999, ed. Harriet Deacon. Cape Town and Johannesburg: Mayibuye Books and David Philip, 1996.

Fux, Vitalis. “Der erste Priester aus dem Stamme der Zulus.” Vergissmeinnicht 63 (1945).

Hermann, Aldegisa M. History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill in the Province of Mariannhill, South Africa. Mariannhill: Mariannhill, 1983. Izindaba Zabantu, September 7, 1928.

Khumalo, Dominic. Interview by author, March 25, 1997, Pietermaritzburg. Tape recording.

Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle 1882-1895, 50, 235-238.

Mariannhill Monastery Archives, Monastery Chronicle 1896-1911, 111.

Mjoli, Natalis. Interview by author, October 22, 1997, Empangeni. Tape recording.

Myeza, Reginald. Interview by author, April 17, 2007, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg. Tape recording.

Mncadi, Malukati. Interview by author, September 1994, Mariathal, Ixopo. Tape recording.

Parle, Julie, “States of Mind: Mental Illness and a Quest for Mental Health in Natal and Zululand, 1868 to 1918.” Ph.D. diss., University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2004.

——–. States of Mind: Searching for Mental Health in Natal and Zululand, 1868-1918. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007.

Respondek, Thomas. Die Erziehung zum Priestertum in der Mariannhiller Mission. Mariannhill: Mariannhill Press, 1950.

UmAfrika. August 16, 1929.

UmAfrika. “Intshumayelo.” January 2, 1931.

UmAfrika. “Izibongo Zika Rev. Fata Edward Mnganga.” November 3, 1945.

UmAfrika. “Ngesikhumbuziso Somufi uRev. Fata Edward Mnganga.” September 28, 1946.

UmAfrika. “Ngesililo Mayelana Nomufi Urev. Fata Edward Mnganga, D.D.” August 25, 1945.

Zeitschrift fur Missionwissenschaft 30, 45-55.

Booklet on Fr. Mnganga’s life for download: Abuse of a Genius: Edward Muller Kece Mnganga 1822-1945: The Story of Father Edward Mnganga, The First Zulu Catholic Priest. by T. S. N. Gqubule

This article, received in 2009, was written by Dr. George Sombe Mukuka, a faculty research manager at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and 2008-2009 DACB Project Luke Fellow.

Photo Gallery

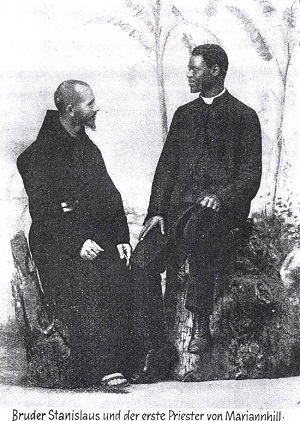

[1] Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1945), 236.

[2] Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1945), 236.

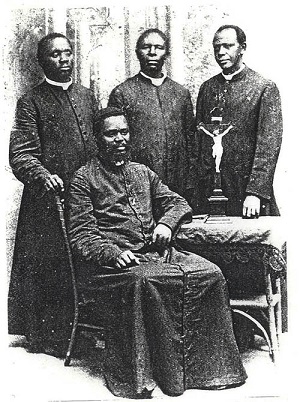

[3] Four first black priests: Ngidi, Mncadi, Mbhele, and Mnganga (seated). Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1924), 251.

[4] Grave of Mncadi and Mnganga. Photo from George Mukuka photo collection, 1997.