Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Waters, Henry Tempest

Introduction

Henry Tempest Waters was born at Newcastle upon Tyne on October 23, 1819. He left the British Isles to work as a catechist for the Society of the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) in the province of Eastern Cape, South Africa. In 1850, he was made a deacon in the Diocese of Grahamstown by Bishop Henry Cotterill. Henry Waters was ordained as a priest in 1855 and was made responsible for St Mark’s Mission, a post he held all his working life. In 1874 Henry Waters was appointed Archdeacon of the Diocese of Kaffraria (later renamed St. John’s).[1] He was attributed as the founder of the Church in Kaffraria, and died in post on November 19, 1883 at the age of sixty-four. He was married with a family, including a son, Henry, who (after training at St. Augustine’s Theological College in Canterbury, England) followed him into the priesthood in 1880 and became Mission Priest in charge of All Saints’ in 1893.

The Anglican Church was a little late arriving in Cape province, the first bishop, Robert Gray, being in post at Cape Town in 1858. The first direct attempt at missionary work in this part of South Africa had been carried out at Southwell, a country charge in the Eastern Cape. Amongst those confirmed at Graaf Reinet on Sunday, April 21, 1850 was Archdeacon Merriman’s servant, Wilhelm, who had been prepared for confirmation by Henry Waters.[2] Thus, he was the first of the Xhosa people to be received into the Anglican Church. The mission at Southwell was first begun in 1849, but any extension to these plans was delayed by another outbreak of the African 100 years war, which took place sporadically between 1797 and 1897.[3] Tensions between the Xhosa tribe and the Europeans boiled over from time to time and insurrections occurred.

There was strong criticism that the Church of England was not doing enough to found missions amongst the Xhosa, and so funds were eventually provided by both the British Government and the Society for Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, culminating in a number of initiatives. In a Clerical Synod at Grahamstown, Henry Waters’ name was suggested for a posting among the Xhosa.

Waters, “one of the most zealous and devoted clergymen in the whole of South Africa” cheerfully gave up his country parish at Southwell in order to undertake planting a mission in what was then the most important, the most remote, and by far the most populous district of Kaffraria: the territory of Sarili ka Hintsa, also known as ‘Kreli’. Kreli was Chief of the Gealeka tribe. The region had a population of nearly 90,000 people scattered all over an area approximating to the size of Yorkshire. There had never been a mission in this region. Geoffrey Callaway, son of the bishop and historiographer of the Anglican Church in that region, described this initiative as “the fountainhead of the future diocese of St. John’s.”

Despite all the preparation done by Bishop Henry Cotterill of Grahamstown, Kreli, and his leaders, to facilitate Waters and his family’s reception, a great native council was convoked to ask why he had come; what he meant to teach; what made Christians come to them; and many other such questions. After satisfactory answers had been given the party was allowed to stay. Aided by a catechist, Mr. R. J. Mullins; a schoolmistress, Miss Gray; and an unnamed agriculturalist, Waters formed a central station with a dedication to St Mark. This was located on Kreli’s side of the White Kei River from where an extension was made to the Tambookies on the colonial side. Under Mr. Mullins’ supervision schools were opened “in all directions.” Services were well attended until in 1856 to 1857 a wave of fanaticism broke out, leaving a trail of death and desolation in its wake.

The fanaticism was the result of a visionary girl’s dreams which, when recounted to the elders of the community, were believed. She purportedly heard the voices of the ancestors telling her to kill all their cattle, destroy all their stores of corn, and not to cultivate their gardens. She promised that when this was accomplished their forefathers would be resurrected and restored to them tenfold, while the English would be engulfed in the sea and drowned. In spite of Waters’ protestations that this was clearly a fable, the girl’s commands were obeyed. The people’s action was without precedent in the history of the nation and, compounding their injurious acts, the devastation of their agricultural assets was followed by a severe famine. The country was rendered desolate and the once prosperous population had to go to neighboring communities to find what work they could, many of them going into slave-labor. The leader of this once proud people could be found wandering in deserted places, scrounging a living where he could, rejected and despised.

During the devastation the European traders left the territory. However, Waters, whose incumbency was described by Bishop Gray as “one of the most difficult and trying posts in the whole of South Africa,” remained at his station. His wife, who had become sick, and their children were removed to a place of safety. He expected to be respected as a clergyman but to have his property destroyed. By staying where he was he managed to save the lives of about 6,000 souls who would have starved, along with many thousands more in the hills of the surrounding region. Mr. Waters was able, with private funds and government aid, to offer humanitarian supplies where they were most needed.

This charitable act struck a chord with the Xhosa and Waters was able to enjoy an extraordinary moral influence among them, which was rewarded by an early resumption of the mission he had inaugurated. Sir George Grey, the Governor of Cape Colony, observed in 1858 that this single act was by far “the most decided movement in the direction of Christianity.”[4] Bishop Cotterill added, “But for this event, we might have labored many years instead of these last two or three, and had very little results”.[5]

On November 1, 1859, All Saints’ Day, Waters and Rev. John Gordon of SPG met the Chief of the amaQuathi people and were granted a piece of land which became the All Saints’ Parish, the nucleus of the cathedral congregation today.

In August 1860, HRH Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Sir George Grey made a visit and witnessed the progress being made.[6] The prince received an address from the Xhosa expressing their appreciation of what had been done for them.[7] There were at that time 800 people living on the station. Many of the members of the village had been confirmed and worship services were very well attended. Two years later, it was reported that the figure had grown to 1,300.

This area had been a refuge of thieves and vagabonds in past times, but now there was no sign of any such activity. Congregations at the services became so large that they had to be divided and two services organized instead. St. Mark’s became a true place of refuge for those who believed in Christianity and for those who simply wanted to ask about or discuss the Christian faith.

By 1865 the station had become an English village in the center of a large native population for whom English investment was affording a decent living. Four deaconesses were employed to look after the children’s schooling, the sick, and the needy. Generally speaking, the order of Christian life was very peaceful and productive. The very dress of those who had been confirmed into the community became different from those who had not, and was a great talking point in the region. People living in the station community had an air of a different quality about them; they dressed in European clothes and built their houses with square structures instead of the traditional circular thatched huts.

Until 1873 the bishops of Grahamstown had supervised the church missions in Kaffraria, though strictly speaking it was not their territory. Nathaniel Merriman, Archdeacon of Grahamstown, undertook a journey through the land and satisfied himself that there was an urgent need for a new bishopric to be formed.[8]

Henry Cotterill, who had been Bishop of Grahamstown from 1856, was transferred to Scotland in 1871 to become coadjutor bishop of Edinburgh. On the death of Charles Hughes Terrott, Primus and Bishop of Edinburgh, in April 1872, Cotterill was elevated to the bishopric. Bruno writes, “Bidding farewell to the diocese, he promised to do everything in his power to see that the Scottish Church would support South African mission work.”[9]

The South African College of Bishops then wrote to the primus and bishops of Scotland in the knowledge that the Scottish Province was keen to found a foreign mission. They interested the Scottish bishops in the great South African field, inviting them to cooperate with SPG and form a Board of Foreign Missions to send a bishop and missionaries to Kaffraria. The Society welcomed this move and willingly consented to place its missionaries under the tutelage of such a bishop provided he was a member of the College of African Bishops. The Scottish Province chose George Calloway, a veteran missionary of Natal. He was consecrated bishop on All Saints’ Day, 1873 in St Paul’s Church, Edinburgh.[10]

At the first Synod of the recently created Kaffraria diocese, held in November 1874, the name of the bishopric was changed to that of St. John’s and the Rev. H. T. Waters was made Archdeacon.

The headquarters of the diocese of St. John’s was moved from Pondoland to Umtata in 1877. At that time there was only one building at Umtata, which soon became well populated. The town owed its founding to Bishop Calloway and is now the most important settlement in the region.

During the Gealeka War (1877 to 1878) and the Pondomisi Rebellion in 1880, European and native Christians sought refuge and found protection within Umtata. Churches and the mission were fortified. Although a few professed Christians joined the dissidents, a hundred to one were loyal and Archdeacon Waters testified, “Not a few died fighting for the Queen!” Bishop Calloway’s erudite summary of the whole incident was held up in government circles as a document of an educated Englishman who had become as well if not better acquainted with African problems than the local people themselves.

Henry Tempest Waters, attributed as the founder of the church in Kaffraria, died at Cape Province on November 19, 1883, at the age of sixty-four. For twenty-eight years he only left his post in order to travel up and down the district, and to attend the synods and other regional meetings in the province as duty required. He is buried in a grave beside the All Saints’ Church Hall of All Saints’ Cathedral at Ngcobo, [formerly Engcobo]. This hall used to be the church before the cathedral was built. At his death, instead of the solitary mission of 1855, there was an organized body of twenty clergymen (his son being among the number) with a bishop at its head. Schools and churches studded the land, “from the Kei eastwards to the very borders of the Natal,” and there were no fewer than forty-eight out-stations in connection with St. Mark’s. On January 3, 1900, a noble central church was opened at St. Mark’s in memory of Archdeacon Waters, the “father” of the diocese. All the work seemed to stem from his labors, and all the native clergy were in lineal descent from him. A very large number of native Christians looked upon him as the father of the community ―a very fitting memorial indeed.

A. C. Stuart Donald

Notes

-

"The name Kaffraria refers to the territories along the southeast coast of Africa that were colonized by the Portuguese and the British. The term referred more specifically in the 19th century to those lands inhabited by the Xhosa-speaking peoples of the area, now part of South Africa’s Eastern Cape province." [see http://www.britannica.com/place/Kaffraria]. It is no longer an official designation and is used here due to its historical context and is not reproduced as an endorsement of its etymological origin.

-

Graaf Reinet is the fourth oldest town in the South African Eastern Cape Province and was founded by the Dutch East India Company in 1786.

-

Southwell Mission: Bathurst Cape, established in 1849, was located at Lombard’s Post Farm and its first resident minister was Rev. Henry Waters. The original wooden structure was replaced in 1868 by a stone building whose foundation stone was laid by Archdeacon N. Merriman.

-

George Grey (1812 to 1898) KCB; soldier, explorer, Governor of Australia and twice Governor of New Zealand and Governor of Cape Colony, 1854 to 1861. A writer, he went on to become the 11th Premier of New Zealand.

-

Henry Cotterill (1812 to 1886) MA DD; Bishop of Grahamstown, South Africa (1856 to 1871); coadjutor Bishop of Edinburgh (1871); Diocesan Bishop of Edinburgh (1872 to 1886).

-

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1844 to 1900) KG KT, son of Queen Victoria and her Consort Prince Albert.

-

The Xhosa people, a Bantu ethnic group living in South Africa, refer to themselves as amaXhosa and their language is called isiXhosa.

-

Nathaniel James Merriman (1809-1882) DD; Archdeacon of Grahamstown; Dean of Grahamstown; Bishop of Grahamstown (1871-1882).

-

Allan David Bruno (b. 1934) AKC, Overseas Chaplain to the Episcopal Church in Scotland (1971- 1975).

-

Now known as St Paul’s and St George’s Church.

Bibliography:

Pascoe, C. P. Two Hundred Years of the SPG: An Historical Account. London: SPG, 1901.

Acknowledgements

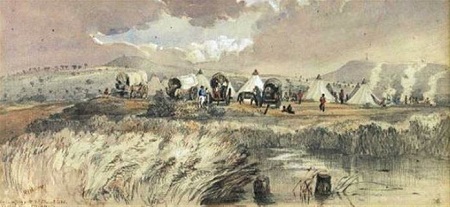

I would like to thank Lucy McCann, archivist of the USPG archives at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, who made available the watercolor of unknown artist and other research details; and to the Very Revd. Gerald Stranraer-Mull, Dean Emeritus of the Diocese of Aberdeen & Orkney, who assisted me with the narrative and the picture of the grave. I would also like to thank the staff of the National Library of Scotland who produced background information from their collections, and to Sheila Watson who was my proof-reader.

A. C. Stuart Donald FSA Scot is Honorary Archivist and Keeper of the Aberdeen Diocesan Library. The primary source for this piece was Pascoe, C. P. Two Hundred Years of the SPG: An Historical Account. London: SPG, 1901. [Account abridged from pp. 280; 297; 307-9; 313; 316; 316e f k 895-6].

Photo Gallery