Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Weston, Frank

(Zanzibar)

(Zanzibar)

Weston was born on the south side of London on September 13, 1871. His father, the head of a firm of tea brokers in Mincing Lane and a strong evangelical Christian, died when Weston was only eleven years old.

Weston went to Dulwich College and to Trinity College, Oxford. During his college days, he was a good debater, and delighted in arguments on any subject. While in residence at Oxford, Weston joined the Guild of St. Matthew. He left Oxford in June 1893 and in August went to live at the College Mission at Stratford-atte-Bowe.

Before he was ordained deacon, the Council at the College Mission was asked to give an evaluation of his work. Having seen more than a year of his work as a layman, they gave their unanimous approval. In June 1896, Weston left Stratford and went to work at St. Matthew’s, Westminster. The time he spent at St. Matthew’s, along with the years at Stratford, formed Weston’s actual experience of working in a church which was gradually becoming liberal in its approach to vital issues. After he had worked at St. Matthew’s for two years, Weston offered himself up for missionary work in Africa. He arrived in Zanzibar in 1898.

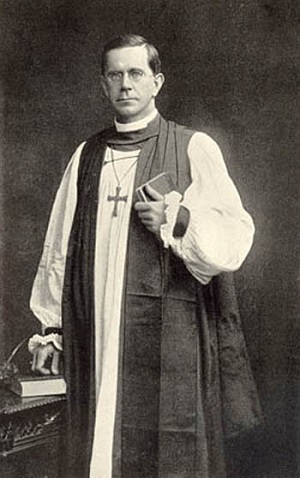

In Zanzibar, Weston trained candidates for Holy Orders. He had a vision of a vigorous African Church with her own theology. In 1901, Weston was made principal of a school at Kiungani. He at once instituted reforms and compiled Swahili books on arithmetic, geography, and grammar. In 1903, Weston became the first chancellor of the diocese of Zanzibar. On October 18, 1903 Weston was consecrated and, on November 6 of the same year, he was enthroned as bishop of Zanzibar. Although Weston was a great missionary scholar, administrator, and preacher, the undue relaxation of historic teaching and discipline in the name of “comprehensiveness” by the Anglican Communion often gave him cause for anxiety. This troubling trend exhibited itself at the 1913 Kikuyu Conference and in a collection of essays called “the Foundations.”

In June 1913 a conference for missionaries was held at Kikuyu in what was then called British East Africa. Representatives were present from the Church of Scotland Missions, the African Inland Mission, the United Methodist Mission, and the Church Missionary Society, representing the Church of England. The chairman was Bishop J. J. Willis of Uganda. The conference met to discuss a possible federation of the various missionary bodies working in the area. The basis of the federation, it was argued, would be the acceptance of the Scriptures as the supreme rule of faith and practice; the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds as the expression of fundamental Christian belief; common membership between churches; regular administration of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper and a common form of organization. Apart from the representatives of the Seventh Day Adventists, the Gospel Mission Society, the German Lutheran Mission, and Friends Africa Mission, the rest of the representatives at the 1913 Kikuyu conference approved the federation plan and signed the proposals for consideration by their home societies. Those who did not sign the proposals however, expressed full sympathy with the proposed federation plan.

At the close of the conference Bishop Peel of Mombasa presided over a celebration of the Holy Communion service according to the rites of the Book of Common Prayer assisted by the Rev. J. E. Hamshere, of the Church of Scotland Mission in the chapel of the Church of Scotland Mission. All the delegates, apart from the Friends who do not believe in sacraments, participated in the united communion service. The Rev. Norman Maclean who was present at the 1913 Kikuyu conference described it as an “epoch-making event, … the impulse of which will be felt throughout every mission field in the world.”

The delegates left Kikuyu with high hopes that the federation would soon be in operation. On August 5, 1913 Bishop Weston of Zanzibar who was not present at the 1913 Kikuyu conference wrote a letter of protest to the Archbishop of Canterbury demanding an official inquiry into the proceedings at Kikuyu. By this time, Weston had become concerned with the excesses of modernism and liberal thought that were gaining hold throughout the Church of England. He had earlier written to the Archbishop of Canterbury about modernism as a hindrance to the progress of the Gospel. In June 1913 Weston read the collection of essays published as “Foundations” and determined to send a response to the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the midst of all this, Weston heard of the Kikuyu conference and the attempt by the two Anglican bishops, Peel and Willis, to create a federation of denominations in East Africa. He called upon the bishops of Uganda and Mombasa to make a public admission that they had not faithfully emphasized that holy communion in the Anglican church was different from that administered in Protestant bodies and to recognize the difference in church doctrine which made it impossible to take communion at another church’s altar and the need for Episcopacy in the church.

Weston published a pamphlet in the form of an open letter entitled “Ecclesia Anglicana - For What Should She Stand?” addressed to the bishop of St. Albans who had recently suppressed an attempt to introduce the practice of the veneration of the Virgin Mary into the diocese. The Kikuyu conference seemed to him an undue relaxation of historic teaching and discipline in favor of heresy and schism. The “Foundations,” according to Weston, were dangerously subversive of Anglican teaching. In this letter, Weston expressed his deep shock at what had happened at the 1913 Kikuyu conference and called for the Anglican faith and order to be upheld and for the condemnation of modernism and the Kikuyu proceedings. The united holy communion service, according to Weston, was a denial of Anglican practices. He challenged the Church of England to declare her mind plainly, and to cease from being what one would call “a society for shirking vital issues.” In his letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Weston wrote: “We are bound to declare them [Nonconformist celebrations of the Communion] null and void, except as spiritual communion. … a man must be in loyal fellowship with the Episcopate before he may receive Holy Communion, it is of no avail to reassert this truth hourly, and yet to invite to the reception of the Blessed Sacrament Christians who are in open rebellion to that Episcopate.”

Weston’s letter raised the question of the coherence of the Church of England in particular and of the Anglican Communion in general. He argued that if the two bishops were not prepared to publicly recant their views, they should appear in an open assembly chaired by Archbishop Randall Davidson of Canterbury. The reason for appeal to the Archbishop was that, because there was no independent Province of East Africa at the time, the Archbishop was the one to whom these bishops all owed canonical obedience.

The letter of indictment was written at the end of September 1913, and Weston was invited by Archbishop Randall Davidson to meet with him on February 7, 1914. Two days later the Archbishop issued a statement in which he made it clear that there would be no trial of the two bishops whom Weston had accused of “propagating heresy and committing schism.” In his letter the Archbishop wrote: “Looking carefully at present-day facts and conditions, I have no hesitation in saying that in my opinion a diocesan bishop acts rightly in sanctioning, when circumstances seem to call for it, the admission to Holy Communion of a devout Christian man to whom the ministrations of his own church are for the time inaccessible.”

The Archbishop did not allow proceedings for heresy on the grounds that the Kikuyu proposals had not yet been implemented. In his conclusion the Archbishop said: “The subject of Reunion and Intercommunion is with us day by day: it is not going to be forgotten; our efforts are not over: we ask continuously for Divine guidance towards the haven where we would be. We do not, I am persuaded, ask in vain.”

As it seems to be the characteristic of the Archbishops of Canterbury, Davidson’s solution was a compromise in the sense that he refused a heresy trial–which Bishop Weston had demanded–but appointed fourteen bishops from different provinces to advise him on the issue at hand in a meeting later that year, in July 1914, a few days before the outbreak of World War I.

Weston and the Archbishop met again on February 25, 1914 and on August 26, 1914, after the Consultative Committee meeting. Weston was asked what he would do if the findings of the Consultative Committee went against him. Weston gave three alternatives. The first would be to join the Roman Catholic Church without seeking ordination but to live as a layman, the second to be out of communion with the diocese of Mombasa and the diocese of Uganda, and the third to retire into lay communion in the Church of England. Weston eventually settled for the second alternative.

In 1914, Weston drew up his own proposals for a Central Missionary Council of Episcopal and Non-Episcopal Churches in East Africa. These proposals included a draft service containing Acts of Faith, Hope and Charity, Self-Surrender and Communion. He recommended that wherever possible the service should be held in a building other than the church, so that the sense of guilt of disunion may be deepened in the hearts of all the participants. Weston also prepared a case for the Consultative Body in his seventy-page document entitled, “The Case Against Kikuyu - a Study of Vital Principles.” In this document, Weston argued that the local bishop is the link with the Catholic Church and the College of Bishops is the complete bond of union, of which the local bishop is its point of contact with the individual soul. Bishop Peel and Bishop Willis also prepared a case for the Consultative Body in a sixty-four page document entitled “Steps towards Reunion.” In this document, the two bishops presented an honest attempt to interpret what they believed to be the spirit and intention of Jesus Christ for His church in East Africa.

In April 1915 the Archbishop issued a seventy-page statement named “Kikuyu” in which he showed that he was more interested in the preservation of a working unity in the Anglican Communion than in the theological or pastoral issues raised by the Kikuyu controversy. In his judgment, the Archbishop did not support the idea that non-Anglican churches could simply be thought of as outside the church. On the other hand it was not satisfactory to sanction the receiving of Holy Communion by Anglicans at the hands of non-Anglican ordained ministers. The Archbishop’s judgment satisfied neither Bishop Willis and Bishop Peel nor Bishop Weston.

For the next nine years after the Archbishop’s judgment, Weston went on normally with his episcopal duties in Zanzibar. In 1924, his health began to fail him and he died on November 2, 1924 at 4.30 a.m. Weston devoted his life to Africa and he has rightly been described as an apostle to Africans.

Christopher Byaruhanga

Sources:

Capon, M. G. Toward Unity in Kenya: The Story of Co-operation Between Missions and Churches in Kenya 1913-1947. Nairobi: Christian Council of Kenya, 1962.

Smith, H. Maynard. Frank, Bishop of Zanzibar. London: SPCK, 1926.

Weston, Frank. The Case Against Kikuyu: A Study in Vital Principles. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1914.

Willis, J. J. Towards a United Church 1913-1947. London: Edinburgh House, 1947.

Source of photos: H. Maynard Smith, D.D., Frank, Bishop of Zanzibar – Life of Frank Weston, D.D. 1871-1924 (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York and Toronto: The Macmillan Co., 1926).

This article, received in 2006, was researched and written by Rev. Dr. Christopher Byaruhanga, 2005-2006 Project Luke fellow and Associate Professor of Historical Theology at Uganda Christian University, a DACB Participating Institution. He is also the liaison coordinator at UCU.

Photo Gallery