Kayizzi, Jonathan

Kayizzi Jonathan was one of Uganda’s first three Protestant priests when he was ordained on May 31, 1896, by Alfred R. Tucker of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), serving as the third bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa (including Uganda). [1] The other two were Revds Lutamaguzi [aka Duta] Henry Wright and Mutakyala Yairo [after Jair or Jairus]. The above three are also Uganda’s first priests as the Catholic Church in Uganda did not promote any Ugandan to priesthood until 1913.[2]

Kayizzi’s surname was written as Kaidzi during most of his life, but it orthographically evolved to Kayizzi. His first name appears as Yonasani, Yonathani, Yonatani, Yonazani, and Yonazi, but they all attempt to localize the English name Jonathan in Luganda.

He was baptized on Easter Sunday, April 25, 1886,[3] barely two months after the lynching of Joseph Serwanga, Mark Kakumba, and Joseph Lugalama on the orders of Mwanga II,[4] who had persecuted Christians from the day he was crowned Kabaka (king) of Buganda on October 10, 1884. And less than two months before the persecution peaked in June.

Kayizzi was one of the exiled Christians in Kabula, Ankole, following the Muslim purge of Christians under Ssekabaka (deceased king) Kalema in 1888.[5] As many as 2,500 Christians fled the country when Muslims turned against Christians.[6] They, however, returned in late 1889 after defeating Muslims and reinstalled Mwanga as Kabaka again.

Following their return to Buganda and the short-lived peace that prevailed, Kayizzi’s star rose like few others within the Protestant community.

He was likely confirmed in the Church on January 18, 1891, when more than seventy converts were confirmed by Tucker, who had arrived in the country on his first trip as bishop on December 27, 1890. [7] This was also the first-ever confirmation in Uganda as no bishop had ever successfully reached Uganda; the first was killed in Busoga on October 29, 1885, and the second died of Malaria in Ussagara (present-day Tanzania) on March 28, 1888.

Kayizzi was appointed a sub-chief for his contribution to Mwanga reclaiming the kabaka-ship. [8] He kept this position until he resigned prior to his ordination as a priest so he could have more time and energy to serve the Lord. [9]

He became a catechist sometime after the first six of January 20, 1891, because he broke new ground on May 28, 1893, when he was ordained one of the first six deacons in Uganda. He attained this feat with Lutamaguzi, Mutakyala, Kisingiri Kizito Zakaliya, Sebwato Nicodemus, and Muyira John. [10] Upon becoming a deacon, Kayizzi was sent with his wife to work in the counties of Busiro and Singo for some time, where he is reported to have done a commendable job. [11]

Much of Kayizzi’s work and time was done in South Kyaggwe, stationed at Ngogwe, now a municipality in the present-day Buyikwe district. Here, he established a working partnership with Revd George K. Baskerville comparable to only that of George L. Pilkington and Lutamaguzi at Mengo. [12] Baskerville states, “Yonasani [Jonathan] Kaidzi [Kayizzi], the native clergyman, is almost entirely in charge of the pastoral work here.”[13]

Baskerville also considered Kayizzi the ableist Ugandan preacher of his generation,[14] stating that his sermons were full of metaphors and illustrations and Europeans who understood Luganda could attest to it,[15] which may partly explain Kayizzi’s meteoric rise in Church and society.

Kayizzi metaphorized Sebwato’s death in 1897 with an axe, saying: “God had lent to us an axe; the axe has done its work, and now God has asked for it back.” [16] Sebwato was an elder to both the young Christians and the young Church for which he was rightly described as a towering figure.[17] Earlier, Sebwato, who was much older than Kayizzi had described him as thus, “It was Kayizzi who broke me in and taught me, coming to my house daily, and now I, though older than he and a bigger man; if he says a thing is not right or seemly, I listen; his word is enough.”[18]

At the time of his death, Sebwato was also the Ssekiboobo (county chief) of Kyaggwe, where Kayizzi and Baskerville worked and was succeeded by Ham Mukasa– another leading Christian– who would later become a figure father to one of Kayizzi’s daughter when she needed one.[19]

In 1898, Kayizzi was suspected of having sleeping sickness and was ill for a long time, though he recovered in 1901 and resumed work.[20] He was also added to the translation committee when reviewing Revd William A. Crabtree’s Elements of Luganda.[21]

Kayizzi is also reported to be a sub-chief again which was not uncommon for many other Ugandans doubled as church leaders and chiefs.[22]

Kayizzi married Ketula Nakato, whose ethnicity the Ugandan historian Nakanyike B. Musisi casts into doubt.[23] Still, they had children. One of whom was Kaidzi [after his father] Eriya (after Elijah), a dedicated organist and pianist who played both musical instruments in Church.[24] He was also the chief assistant treasurer of the colonial government in Uganda and played soccer as a center half.

The same year he was ordained a priest, he gave birth to Namaganda Irene, his most prominent child. Namaganda married Daudi Cwa II, the Kabaka of Buganda, on September 19, 1914, and nearly brought the kabaka-ship to its knees when she decided to remarry after Cwa’s death on November 22, 1939.[25]

By the time of the wedding, Kayizzi, who had been transferred to Buddu in 1912, was pastoring a church in Kako. But before his transfer, he also served as a missionary to Busoga where his work was summed up as “eminently suited.”[26]

Contrary to the polygamous practices of most Baganda men of the day, Kayizzi was a monogamist who inspired the communities he worked in. An old man Taylor talked to while researching his book described Kayizzi as “the millet that fermented the beer” in Kyaggwe for how he kept one wife and vigorously encouraged others to do the same. [27]

As a father, his children give us some insights about the man as a parent. Namaganda attended Gayaza High School, Uganda’s first girls’ school, where she even became a head prefect. One would assume that Nabaweesi Perpetua, another daughter of his, was equally well-educated. Eriya and Irene grew up singing in Church. On hearing that the Kabaka would marry Kayizzi’s daughter, Baskerville, his long-term friend and Archdeacon of Uganda by then, said, “The Kabaka’s selection is a wise one.”[28]

Kayizzi co-authored Life of Mohammad with Baskerville, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK).[29]

When Eugene Stock’s fourth volume of History of the Church Missionary Society went to press in 1916, Kayizzi was still on the roll as a clergy of the Uganda Mission.[30]

Ketula, his wife, died in 1959.

Kimeze Teketwe

Notes:

- Alfred R. Tucker, Eighteen Years in Uganda & East Africa: With Ill. and A Map, vol. 2, 2 vols. (London: Arnold, 1908), 55.

- Sarah E. Dahl, “The Brilliant Career of Joseph Kiwanuka: Christian History Magazine,” Christian History Institute, 2003.

- Martin John Hall, Through my Spectacles in Uganda: Or the Story of a Fruitful Field (London: Church Missionary Society, 1898), 53.

- “Uganda Mission: Original papers, 1923” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1923), 163.

- J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 32.

- John Vernon Taylor, The Growth of the Church in Buganda: An Attempt at Understanding (Westport, Conn, 1979), 263.

- CMS Awake!, Volume 2, Issue 22. 1892. London: Church Missionary Society, 118.

- Tucker, Eighteen Years in Uganda & East Africa, 121.

- Uganda: General correspondence covering topics such as education and the division of the diocese, 1946-1949” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1946-1949), 419.

- The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 19, 1894. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, 130.

- Mullins and Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 85.

- “Kenya Mission: Precis book, 1895-1900” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1895-1900), 38.

- Taylor, The Growth of the Church in Buganda: An Attempt at Understanding (Westport, Conn, 1979), 72.

- The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 24. 1899. London: Church Missionary Society, 598.

- The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 23, Issue 271. 1896. London: Church Missionary Society, 104.

- Mercy and Truth, Volume 5, Issue 60. 1901. London: Church Missionary Society, 280.

- Eugene Stock, The History of the Church Missionary Society (London: Church Missionary Society, 1899), 740.

- Mullins and Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 28.

- The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 20, 1895. London: Church Missionary Society, 36.

- Nakanyike B. Musisi, “Lady Irene Namaganda,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 2021, 13.

- The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 27, Issue 320. 1902. London: Church Missionary Society, 613.

- “Annual letters of the missionaries, 1901-1902” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1901-1902), 118.

- “Annual letters of the missionaries, 1901-1902” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1901-1902), 118.

- Musisi, “Lady Irene Namaganda,” 4.

- Eastward Ho!, Volume 42, Issue. 1932. London: Church Missionary Society, 119-120.

- Musisi, “Lady Irene Namaganda,” 1-23.

- CMS Awake!, Volume 18, Issue 216. 1908. London: Church Missionary Society, 140.

- Taylor, The Growth of the Church in Buganda, 184-185.

- The CMS Home Gazette, Volume 9, 1915. London: Church Missionary Society, 16.

- Mullins and Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 120.

- Eugene Stock, The History of the Church Missionary Society, vol. 4, 4 vols. (London: Church Missionary Society, 1916), 94.

Sources:

“Church Mission Society Archives.” Church Missionary Society Periodicals - Adam Matthew Digital, 2023.

“Church Missionary Society Periodicals.” Church Missionary Society Periodicals - Adam Matthew Digital, 2023.

Dahl, Sarah E. “The Brilliant Career of Joseph Kiwanuka: Christian History Magazine.” Christian History Institute, 2003.

Hall, Martin John. Through My Spectacles in Uganda: Or the Story of a Fruitful Field. London: Church Missionary Society, 1898.

Mullins, J. D., and Ham Mukasa. The Wonderful Story of Uganda. London: Church Missionary Society, 1904.

Musisi, Nakanyike B. “Lady Irene Namaganda.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 2021.

Stock, Eugene. The History of the Church Missionary Society. London: Church Missionary Society, 1899.

Stock, Eugene. The History of the Church Missionary Society. Vol. 4. 4 vols. London: Church Missionary Society Salisbury Square, E.C., 1997.

Taylor, John Vernon. The Growth of the Church in Buganda: An Attempt at Understanding. Westport, Conn, 1979.

Tucker, Alfred R. Eighteen Years in Uganda & East Africa: With ill. and a Map. Vol. 2. 2 vols. London: Arnold, 1908.

About the Author

This biography, submitted in June 2023, was researched and written by Kimeze Teketwe, a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. From Uganda, East Africa, Teketwe holds degrees in missiology and international educational development from Fuller Graduate School of Intercultural Studies and Penn Graduate School of Education, respectively.

Photo Gallery

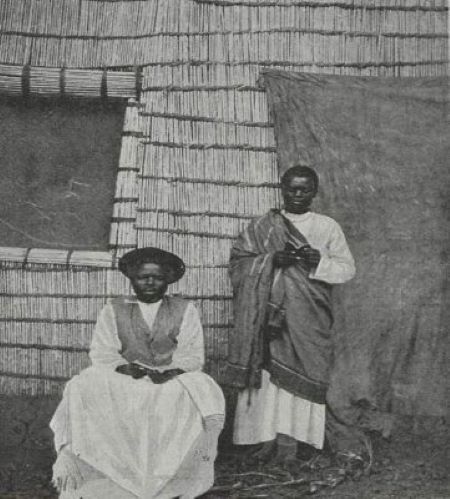

Revd Kayizzi Jonathan standing behind his friend Revd Lutamaguzi Henry Wright. Picture contributed by Teketwe, Kimeze.

Revd Kayizzi Jonathan standing behind his friend Revd Lutamaguzi Henry Wright. Picture contributed by Teketwe, Kimeze.