Sebuwato, Nicodemo (B)

Sebwato Nicodemus was one of the earliest Anglican converts in Uganda, who became a prominent leader in the emergence, development, and spread of Anglicanism in that East African country. Described as “the foremost among the Protestants of Uganda, [and] practically their leader” by the English missionary, Rev. Robert P. Ashe, few converts promoted the activities of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in Buganda as effectively as he did. [1]

With a current membership of over 10.5 million people, the church that Sebwato helped to grow is today considered the strongest Anglican province in sub-Saharan Africa.[2]

His surname has not orthographically evolved and remains popular among members of the Musu [Edible rat] clan in Buganda. His baptismal name appears in archives as Nicodemo, [3][4] Nikodemo, [5][6][7] Nekodemus, [8][9] and Nicodemu [10] but all were attempts to Luganda-nize the New Testament character from whom he took it. [11] He likely was called Nikodemo by most Baganda and wrote it as such, although he signed his letters with his surname. [12][13]

Baptism

Sebwato was baptized on March 30, 1884, by Revd Philip O’Flaherty at Nateete, Kampala, the first site of the CMS mission in Uganda. [14] This would make him an early convert, as the first Anglican baptism occurred on March 18, 1882. [15] About the same time, O’Flaherty journaled that sixty-eight Ugandans had been baptized by March 18, 1884, exactly three years since his arrival in Uganda.[16] Sebwato became a tower of strength for the emerging Anglican Church of Uganda following his baptism. [17]

As a polygamist who also practiced witchcraft before his change of heart and mind, Sebwato had to choose one from his wives, letting others find other suitors, and destroy all his Lubare [spirits and mediums] before he could be baptized. [18] Interestingly, he took the head of his Lubare with him to be baptized, too, but his was deferred because he “failed to satisfy O’Flaherty in examination.” [19]

Mentor

Sebwato arrived at the CMS mission station considerably older than most converts and prospective converts who tended to be young. He is estimated to have been about fifty years old when he switched from being Pokino to Ssekiboobo in early 1890s, meaning he may have been in his early forties at the time of his baptism. [21][22]

His age made Christianity relatable to older Baganda and a mentor to a generation of young converts, a role he embraced with much humor. [23] Speaking about a much younger Kayizzi Jonathan, whom he housed for a while, Sebwato said, “It was Kayizzi who brought me in the [church] and taught me, coming to my house daily, and now I, though older than him and a bigger man; if he says a thing is not right or seemly, I listen; his word is enough.” [24] Kayizzi was baptized in 1886, and was ordained one of Uganda’s first three Anglican priests on May 31, 1896.

Relationship with the Katikkiro

As a sub-chief under the Pokino of Buddu during Muteesa I’s reign, he was a good friend of the Katikkiro [Prime Minister] of Buganda Mukasa, a relationship from which the mission regularly profited. [25][26][27][28] Mukasa was Muteesa I’s last Katikkiro and kept his position throughout Mwanga II’s first reign as kabaka of Buganda. Sebwato remained one of his most trusted chiefs. [29]

On one occasion he saved him from being killed by order of Mwanga, who, wanting to avenge the killing of one of his favorite guards by Mukasa, zeroed in on Sebwato as the perfect target to avenge his guard. [30] Mukasa was consequently asked to produce Sebwato for death, the kabaka arguing that he would not be a loss since he even practiced foreign superstition anyway. [31] Mwanga even refused to eat until Sebwato had been killed. [32] This news shocked the mission station where Sebwato was held in high esteem, but they were soon relieved when Mukasa told them he would succeed in persuading the kabaka to let Sebwato live. Instead, Sebwato was whipped in public but not killed. [33]

Church Council

In July 1885, Sebwato was elected one of twelve elders to Uganda’s first Anglican Church Council. [34] The persecution of Christians, which began in early 1885, led missionaries and converts to organize themselves better if they were to survive, which is how the council came into existence. While Mwanga did not expel or kill European missionaries, the courtesy was not extended to his subjects who were daily persecuted.

On January 31, 1885, three young Christians – Lugalama Joseph, Kakumba Mark, and Serwanga Noah – were gruesomely killed in Busega, Uganda, for professing their religious faith. [35] The latter, a Muhima boy, had been saved from enslavers by Sebwato, who took him to the mission station, placing him in Ashe’s care. [36]

Sembera Mackay, the first Anglican convert in Uganda, was also elected to the council, as was Lutamaguzi Henry Wright, who became the leading Ugandan Bible translator in the following decade. Of the twelve, Walukagga Noah, Munyagabyanjo Robert, Bekokoto Shem, and Kizza Frederick Wigram did not survive the height of the persecution in 1886 and are today counted among the martyrs of Uganda. [37]

Despite the persecution and orders for his arrest, Sebwato continued to lead Christians and perform his duties as a sub-chief as much as he was able to. [38][39] He also continued to regularly check on missionaries at Nateete, often with food supplies and inquiries of what they lacked to thrive in their mission. [40]

Exile

Sebwato was one of the Christians who fled to Kabula (in present-day Lyantonde district), Uganda, when Muslims defeated and drove Christians out of Buganda in 1888. The magazine CMS Awake of October 1892 reported that an estimated 2,500 Christians fled to Kabula, in present-day Lyantonde district, Uganda.

In August 1888, Mwanga, who had persecuted Christians throughout his first reign, was dethroned by a combined force of Christians and Muslims, who replaced him with his older brother Kiweewa. Due to his purported dislike of Islam, Muslims turned against Christians, dethroning him too after 72 days and replaced him with Kalema. [41] As Kiweewa was customarily forbidden from being kabaka as the oldest son, Kalema became the first Muslim kabaka of Buganda. Under him, on his orders, Muslims began killing every Christian and members of the royal family as they were seen as threats to his throne. Most of those who were able to flee went to Kabula.

The decision to go to there was Sebwato’s due to his relationship with the Omukama [king] of Ankole Ntare.[42] Having held chieftaincies in [Buddu], a county neighboring Ankole, he had a relationship with the Omukama. [43] Years earlier, a male child of the Omukama was captured by Zanzibari-Arab slavers, and the Omukama reached out to Sebwato to help him redeem him, which he successfully did. [44] This placed him in Sebwato’s debt.

The Omukama, however, soon became concerned at the growing number of refugees in his kingdom and the unrest in Buganda. Reports were also circulating that the dethroned Mwanga had left the Roman Catholic mission at Bukumbi (present-day Tanzania) and was now in Usambiro (again in present-day Tanzania) with Alexander M. Mackay, preparing for baptism as he may have thought this would lead the CMS to help him reclaim his throne. [45] This instability in a neighboring kingdom naturally worried the Omukama.

Sebwato also represented Christians in communication with the Omukama and promoted harmony between Anglicans and Roman Catholics as the two factions also disliked each other. On March 4, 1884, Sebwato wrote to Mackay, mentioning their status as refugees and the friction between them [Protestants] and the Roman Catholic faction, even in exile. [46][47] He wanted his advice on whether it was wise for them to work together with the Roman Catholic party and fight their way to Buganda or give up on their return. [48] Mackay, who had been the de facto leader of the CMS mission in Uganda since his arrival in 1878, was banished from Uganda by Mwanga in 1887. In the end, the CMS party supported a return to Buganda.

Return to Buganda

In October 1889, one year after fleeing, Christians battled their way back to Buganda, driving Muslims into exile in Bunyoro [in present-day Uganda]. In an interesting turn, Christians reinstalled their former archenemy, Mwanga, as kabaka of Uganda for his second reign. Sebwato was one of those who distinguished himself in battle by his bravery. [49] And for his contribution to the reinstatement of Mwanga, he was awarded a chieftaincy as the Pokino, a title for the county chief of Buddu. [50][51]

Confirmation, catechist, and perpetual deacon

Like all Anglicans baptized in Uganda during the 1880s, he remained unconfirmed in the church because no bishop had successfully made it to Uganda to perform the sacrament. James Hannington, the first bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa (including Uganda), was murdered on October 29, 1885, in southern Busoga as he made his way to Buganda. His successor, Henry Parker, suddenly died of malaria in Ussagala (in present-day northern Tanzania) in 1888 as he prepared to move up north to Uganda.

The tide, however, changed in 1890 when Alfred R. Tucker arrived in Buganda’s capital on December 27. A total of seventy Ugandans, including Sebwato, were confirmed on January 18, 1891, at Namirembe, Uganda, the new site of the CMS mission in Uganda. [52] Two days later, he was ordained a catechist. [53] On Trinity Sunday 1893, he was ordained a deacon. [54]

He did not rise again in church rank, but he received the designation of “perpetual deacon” [55] because of his contribution to the development of Anglicanism in Uganda. This could be why he was sometimes addressed as ‘Reverend’ even though he was never ordained a priest. [56] The first Anglican priests in Uganda were ordained about a year after his death.

From Pokino to Ssekiboobo

Fourteen days before Tucker’s first trip to Uganda, Frederick Lugard (then captain, later Sir) had stormed Buganda’s capital, forcing a treaty of cooperation and protection between the Imperial British East African Company (IBEACo.) for which he worked at the time and the kabaka-ship headed by Mwanga. Lugard soon brought the exiled Muslim faction back to Buganda and distributed Buganda counties along religious lines. In this concession, Sebwato, an Anglican, was transferred to Kyaggwe, as Buddu was given to Roman Catholics. The county has an overwhelming number of Roman Catholics believers to this day.

Consequently, he became a Ssekibooko, the county head of Kyaggwe. [57][58][59] Kayizzi, who had resigned from his political role to focus on religious work, and the English missionary Rev. George Knyfton Baskerville were also posted to Kyaggwe to work under Sebwato. [60] Not only are the three men pioneers of Christianity in Kyaggwe, but they were also the first individuals to advance Christianity to eastern Uganda, particularly in Busoga. [61][62][63]

Death

Sebwato died on March 26, 1895. [64] He was in his fifties, yet his death was attributed to malaria and pleurisy he had got from a trip with Lugard to bring back exiled Muslims from Bunyoro.

In his eulogy, his mentee, Kayizzi, metaphorized his life by comparing it to an axe, saying, “God had lent us an axe; the axe has done its work, and now he [God] has asked for it back.” [65] Baskerville added, “Dear old man. When shall we see the likes of you again?” [66]

Legacy

Sebwato is the founder of a church at Ngongwe, Mukono, one of the oldest Christian Centers in Uganda, established in 1893. [67] [68] He was also instrumental in the construction of the first cathedral in Uganda on the summit of Namirembe Hill, Kampala, Uganda, which opened on July 31, 1892, though the extent of his contribution is sometimes exaggerated.[69] [70] Nonetheless, it collapsed due to natural causes and the second was opened on July 14, 1895, three months after his death.

Kimeze Teketwe

Notes:

-

Robert P. Ashe, Chronicles of Uganda. (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1894), 48.

-

Andrew McKinnon, “Demography of Anglicans in Sub-Saharan Africa: Estimating the Population of Anglicans in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda,” Journal of Anglican Studies 18, no. 1 (2020): 42–60, 42.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, 622.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 19, 1894. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, 352.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, 1884, 755.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15,1890, 357.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 29, Issue 339. 1902. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, 35.

-

“Missionary Pamphlets, vol. 7” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1875-1890), 256.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 11, 1886, 881.

-

“Uganda Mission: Original Papers, 1920” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1920), 673.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 29, Issue 339. 1902, 35.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890, 34.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890, 28. Baganda are the people of Buganda; one is called a Muganda.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, 1884, 755.

-

J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda. (London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 28.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, 1884, 755

-

Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 28.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, Issue. 1884, 755.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, 1884, 755.

-

Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 28.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, Issue. 1884, 755.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 9, 1884, 755.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 18, 1893, 200.

-

Martin J. Hall, Through My Spectacles in Uganda (London: Church Missionary Society, 1898), 52.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 18,1893, 200.

-

‘Tucker of Uganda: Artist and Apostle, 1849-1914’, London, 1929, 206pp (Uganda)” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1929), 186.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 20,1895, 367.

-

Pokino is “the title for the county chief of Buddu, one of the counties of Buganda in Uganda.

-

“‘Tucker of Uganda: Artist and apostle, 1849-1914’, London, 1929, 206pp (Uganda)” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1929), 60.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 22, Issue 263. 1895, 166.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890, 622.

-

Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda, 113.

-

Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda, 222.

-

“Missionary Pamphlets, vol. 7” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1875-1890), 881.

-

“Missionary Pamphlets, vol. 7”, 881.

-

“Missionary Pamphlets, vol. 7”, 881.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 18, Issue. 1893, 204.

-

Kimeze Teketwe, “Lugalama Joseph.,” Medium, July 10, 2023.

-

Muhima is a single member of the Bahima people group living in present-day Ankole, southwestern Uganda.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 18, 1893, 204.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 11, 1886, 492.

-

Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda, 148.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890, 520.

-

Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda, 222.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1903-1904” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1903-1904), 160 -161.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1903-1904,” 86.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1903-1904,” 86.

-

Ashe, Chronicles of Uganda, 121-122.

-

“‘Mackay of the Great Lake,’ London, 1917, xi, 144pp (Uganda)” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1892), 131-132.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, 1890, 28.

-

Sarah Geraldine Stock, The Story of Uganda and the Victoria Nyanza Mission (London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1899), 157.

-

Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda, 223.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15,1890, 357.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, Volume 15, Issue. 1890, 357.

-

“‘Tucker of Uganda: Artist and Apostle, 1849-1914’, London, 1929, 206pp (Uganda)” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1929), 60.

-

Alfred Robert Tucker, Eighteen Years in Uganda and East Africa. vol. I, 2 vols. (London, UK, 1908), 111.

-

Mullins and Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda, 85.

-

Mercy and Truth, Volume 22, Issue 251. 1918, 66.

-

Mercy and Truth, Volume 22, Issue 251. 1918, 66.

-

“Kenya Mission: Precis Book, 1892-1895” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1892-1895), 62.

-

Ssekiboobo is the official title of Kyaggwe county chief.

-

Eugene Stock, The History of the Church Missionary Society. vol. III, 4 vols. (London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1899), 446.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1893-1895” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1893-1895), 239.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 29, 1904, 497.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1893-1895” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1893-1895), 439.

-

“Annual Letters of the Missionaries, 1893-1895” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1893-1895), 239.

-

“Uganda Mission: Original Papers, 1923” (Government Papers, The National Archives, Kew, 1923), 7.

-

Stock, The History of the Church Missionary Society, 449.

-

“Uganda Mission: Original Papers, 1920,” 4.

-

“Uganda Mission: Original Papers, 1923,” 7.

-

“Uganda Mission: Original Papers, 1920,” 673.

-

Mercy and Truth, Volume 5, Issue 60. 1901, 280.

-

Yudaya Nangonzi, “Namirembe Cathedral Has Seen It All at 100 Years,” The Observer – Uganda, November 11, 2015.

Sources:

Ashe, Robert P. Chronicles of Uganda. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1894.

Ashe, Robert P. Two Kings of Uganda. London, UK: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1890.

Mullins, J. D., and Ham Mukasa. The Wonderful Story of Uganda. London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1904.

Stock, Eugene. The History of the Church Missionary Society. Vol. III. 4 vols. London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1899.

Stock, Sarah Geraldine. The Story of Uganda and the Victoria Nyanza Mission. London, UK: Church Missionary Society, 1899.

Tucker, Alfred Robert. Eighteen Years in Uganda and East Africa. Vol. I. 2 vols. London, UK, 1908.

This biography, submitted in January 2023, was researched and written by Kimeze Teketwe, whose work explores the interaction of culture, education, and religion in East Africa from anthropological and historical lenses. Teketwe holds graduate degrees in missiology from Fuller Graduate School of Intercultural Studies and international educational development from the University of Pennsylvania.

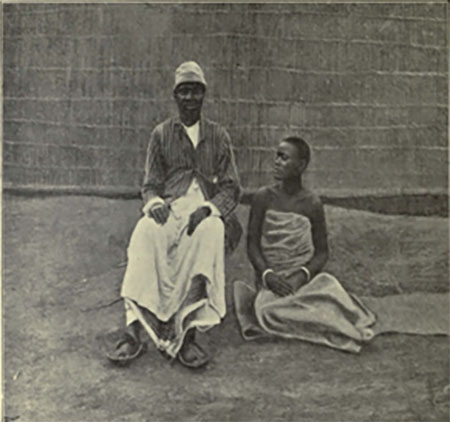

Photo Gallery:

Figure 1: Nicodemus Sebwato with his wife, Julia (in probably 1891). [20]