Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.De Foucauld, Charles Eugène (A)

Your vocation is to shout the Gospel from the rooftops, not in words, but with your life. -Charles de Foucauld

His life was the stuff of a French opera. An orphan, and later a graduate of the military academy Saint-Cyr, he was passionately in love with a beautiful mistress. Then his regiment left for Algeria, where the desert and its people fascinated him. The fashionable Parisian agnostic next converted to Christianity, abandoned a successful military career, became a Trappist monk, and journeyed to the Holy Land. He later returned to Africa as a solitary hermit monk, where he lived among the poorest of the poor. His final years were spent in North Africa, most of them in the middle of the Sahara, where anti-French rebels assassinated him on December 1, 1916.

Such was the legacy of Charles Eugene, viscount of Foucauld, born in 1858 and left an orphan six years later. The Foucaulds were a titled family whose sons had fought honorably in French wars and whose family motto was “Never Retreat.” Charles was admitted to Saint-Cyr, where he spent more time in escapades than in preparing for a military career among the elite of French soldiery. After graduation Charles broke with Mimi, his mistress, and became a soldier, but nagging religious questions now filled his consciousness. “My God, if you exist, make your existence known to me,” he prayed, and sought the guidance of a well-known spiritual director who told him to make his confession and receive communion, and he would become a believer. Actually, it worked. Charles later wrote of the experience, “As soon as I believed there was a God, I understood that I could not do anything other than live for him. My religious vocation dates from the same moment as my faith.”

Armed with a comfortable inheritance, he headed for the Holy Land, where he visited sacred sites. He joined a Trappist monastery in Armenia, and stayed there for nearly seven years. Charles increasingly concentrated on imitating what he called “the hidden 1ife of Jesus,” who lived among the poor. Employed as a custodian in the convent of the Poor Clares in Nazareth, he wrote, “I have now the unutterable, the inexpressibly profound happiness of raking manure.” After seeking ordination in France in 1901, he returned to North Africa to live the remaining fifteen years of his life. Charles hoped to found a community of Little Brothers (and later Little Sisters) whose lives would be spent among the poor. None joined him in his lifetime, but by the 1970s more than 250 Brothers and 1,000 Sisters lived in small “fraternities” in different nations; a union of priests in secular vocations was launched in 1952, followed by two groups for lay women and men.[1]

Although he had mustered out of the army, Charles retained links with its members. In 1905 an old military comrade invited him on an expedition deep into the Sahara, where Charles built a hermitage in the remote oasis village of Tamanrasset. He lived simply among local people, dressed in a white robe. While he wrote a Tuareg dictionary and maintained respect for Islam, his was not of a scholarly bent. Nor did he seek to convert local peoples, but to live a life of Christian compassion among them. Villagers called him a marabout, or holy man.

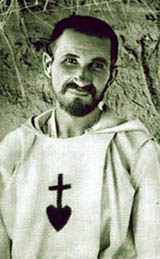

Subsisting on a diet of local dates and meal, he lived in a small house of stones and reeds. Here he kept the reserved sacrament exposed before a lamp. Pictures of him taken in these years reveal a balding, gaunt figure, missing several teeth, skin parched, eyes burning with intensity. Seeking to emulate the hidden life of Jesus and to welcome all humanity, he wrote:

I want to accustom all the inhabitants, Christians, Muslims, Jews, and nonbelievers, to look on me as their brother, the universal brother. Already they’re calling this house “the fraternity” (khaoua in Arabic) – about which I’m delighted – and realizing that the poor have a brother here – not only the poor, though: all men.[2]

His death was complicated by his close association with the French military. Arms were stored in his hermitage, which by 1916 had meter-thick high walls. French military patrols stopped there, and to them and the Arabic-speaking populations Charles was a local French agent. The Senoussi tribesmen who killed him were using World War I as an opportunity to purge their homelands of foreign infidels. On the evening of December 1, 1916, a local person, bribed by the invaders, knocked on his door, pretending to deliver some mail. Armed rebels forced their way in, held the priest captive, ransacked the place, and shot him in the head.

It was the destiny of Charles de Foucauld to die in obscurity, and it was not for many years that he became a spiritual presence, one attracting both readers and actual followers. The austerity of his life and teachings would attract only a selective following, and the hidden life of Jesus, which he found at the core of the Gospel, was not a mainstream theme for most clergy. Near the end of his life he summarized his faith:

Jesus came to Nazareth, the place of the hidden life, of ordinary life, of family life, of prayer, work, obscurity, silent virtues, practices with no witnesses other than God, his friends and neighbors. Nazareth, the place where most people lead their lives. We must infinitely respect the least of our brothers … Let us mingle with them. Let us be one of them to the extent that God wishes … and treat them fraternally in order to have the honor and joy of being accepted as one of them. [3]

Frederick Quinn

Notes:

-

Charles de Foucauld, Letters from the Desert, trans. Barbara Lucas (London: Burns & Oates, 1977), 143-144. See also Robert Ellsberg, “Charles de Foucauld,” in Susan Bergman, ed., Martyrs (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1998).

-

Quoted in Charles de Foucauld, writings selected with an introduction by Robert Ellsberg (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1999), 89.

-

Ellsberg, “Charles de Foucauld,” in Bergman, Martyrs, 297.

This article is reproduced, with permission, from African Saints: Saints, Martyrs, and Holy People from the Continent of Africa, copyright © 2002 by Frederick Quinn, Crossroads Publishing Company, New York, New York. All rights reserved.