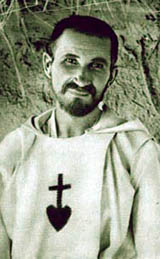

De Foucauld, Charles Eugène (C)

Imagine that, for several days now, an unknown reader has been consulting geography books at the Bibliothèque nationale d’Alger, whose director is Mac Carthy, little known to the general public, but not unknown to learned societies: he had led a wandering life through the three Algerian departments, and had collected extensive documentation. He obtained a mission to explore the entire Saharan region south of the Atlas Mountains, but various reasons, one of which was his impecuniosity, prevented him from realizing his dream. He was nonetheless at the origin of Saharan exploration and the Algerian railroads. In this respect, MacCarthy’s attention is drawn to this young man, who appeared to be passionate about geography. He approached him. Providence had arranged this memorable and invaluable meeting. The young man in this scenario was Viscount Charles de Foucauld.

Imagine that, for several days now, an unknown reader has been consulting geography books at the Bibliothèque nationale d’Alger, whose director is Mac Carthy, little known to the general public, but not unknown to learned societies: he had led a wandering life through the three Algerian departments, and had collected extensive documentation. He obtained a mission to explore the entire Saharan region south of the Atlas Mountains, but various reasons, one of which was his impecuniosity, prevented him from realizing his dream. He was nonetheless at the origin of Saharan exploration and the Algerian railroads. In this respect, MacCarthy’s attention is drawn to this young man, who appeared to be passionate about geography. He approached him. Providence had arranged this memorable and invaluable meeting. The young man in this scenario was Viscount Charles de Foucauld.

The de Foucauld family was jubilant in Strasbourg on September 15, 1858: its circle was enlarged by the addition of a child given the first name of Charles; its heredity, this “geôle”, as Bourget calls it, is heavy with glorious memories and eminent services to the honor of France and the Church. But at barely six years of age, Charles was orphaned of both parents. Entrusted to the care of his grandfather, he was not understood: no human being can truly understand another human being, no one can, in truth, arrange everything for the happiness of another. As a high-school student, haughty and full of character, he felt the full weight of profound loneliness. But he was also curious, eager to learn, and he loved to read; during the school year, he would write to his grandfather about the pleasure he promises himself in reading and rereading during the vacations. In fact, as a teenager, he nourished himself with all the literature a young man open to the things of the mind could do. It was the time of V. Cousin, Hegel, Kant, Littré, even Baudelaire. He still admired ancient authors, and loved Sallustus and Epictetus. Nevertheless, he did not come across a letter from Voltaire, who wrote to a young girl who was also a lover of letters: “I invite you to read only those works that have long been in the public eye and whose reputation is unequivocal. There aren’t many of them, but you’ll get much more out of reading them than from all the bad little books with which we are inundated.” This advice, valid in the 18th century, was also, and even more so, true in the 19th. This lack of a criterion for a guide in his readings that presented the various forms of human thought down the centuries under the same aspect of probable veracity, inevitably engendered skepticism. On the other hand, Charles de Foucauld declared: “I had no bad masters, on the contrary, all were very respectful; even those that are neutral do harm by being so.” And he added: “The faith with which so many different religions are described seemed to me to be the condemnation of all; less than any of them, the faith of my childhood seemed to me admissible, with its 1 = 3, that I couldn’t bring myself to assert anything.” Nevertheless, “I remained twelve years without saying or believing anything. But my respect and esteem remained intact”. The Church and its ministers were respected, but faith had sunk beneath this heap of diverse knowledge. Nevertheless, a shipwreck is not always final.

As a bachelor, he had to choose the direction of his life. Noble and wealthy, he naturally joined the army, and became a cavalryman.

Military life

His grandfather, Colonel de Morlet, who had raised him since his mother’s death, would have liked Charles de Foucauld, as a former polytechnician, to try the Ecole Polytechnique. Too lazy for that program, Foucauld opted for Saint-Cyr. The flame of Saint-Cyr did not burn in his heart, nor did the enthusiasm of the great emotions of the army illuminate his soul. He was sensual, and enjoyed all the easy pleasures his fortune allowed him. As a result, he left the school without a sparkle and, driven solely by the spirit of caste, entered Saumur. Here, too, his military life was not nearly as ideal as it had been at Saint-Cyr. Officer cadets live in pairs. Fate chose Antoine de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Morès, as his roommate. They formed a friendship that would never be broken by adversity. But they were also united by a taste for pleasure, and their bedroom became an elegant boudoir. Lavish outings were part of the program, meticulously organized by the viscount. And yet, the guests were not unaware that, during these festivities, Charles de Foucauld, while doing his utmost to laugh and sing, would suddenly become speechless, motionless, his gaze lost. In the end, he graduated from Saumur eighty-seventh out of eighty-seven students.

As an officer, he was appointed to the 4th Hussars in Pont-à-Mousson, where his eccentricities continued to stand out. He planned a night party on the waters of the frozen Moselle, with fir trees lit to light and warm the dancers. Pound after pound of punch cast a fiery glow into the night. In this town, he made an excellent friend, the Duke of Fitz-James.

But then his regiment left for Sétif. He put the finishing touches to his disorderly conduct, which forced the military authorities to intervene. Lieutenant de Foucauld was ordered to submit to the military code of honor. His colonel’s injunction was expressed in these words: “That’s an order.”” Foucauld stiffened and hid behind his pride. He refused to submit and resigned. He then retired to Evian. A votary of virtue, in moments when a dark sadness overwhelms him, he remains the volunteer of derangement. Perhaps in the depths of his soul, the words of Saint Paul remain. “I do the evil I hate, I do not do the good I love.” Evian is in Capua.

In May of 1881, a bolt of lightning streaked across the political horizon. Bou Amama, a seditious adventurer, provoked a rebellion and revolt in the south of Oran. Volunteers were called for. Foucauld asked to be reinstated in the army. The generous Minister of War gave him back his command. It turned out to be an important campaign, for it was a serious turning point in Foucauld’s life.

Yet his will was to be exercised on another, far more dignified level. He experienced the emotions of ever-imminent danger: ambushes, guerrilla warfare, attacks in the dead of night; he esteemed the value of the soldiers whose lives he had to spare, often in spite of themselves; he came close to a new world, which he soon surrounded with an affection that was returned to him. The social sense was awakened in him. He was taken by the beneficial value of the desert, sometimes isolating himself in it with a solitude which he loved. And above all, his soul was invaded by a groundswell of the supernatural in the presence of the sight before him five times a day, of Arabs prostrating themselves on the ground and uttering aloud: “God alone is great.” Foucauld, too, could ratify the words that Psichari would later write: “Because I know that great things are done through Africa, I can demand everything of her and I can demand everything of myself through her. Because she is the figuration of eternity, I demand that she give me the true, the good, the beautiful and nothing of the world.” So he decided to delve into its mysteries. To do so, he asked for a leave of absence, which was refused, and so he resigned, never to go back. The trip to Africa would take place.

Reconnaissance in Morocco

Though daring, Foucauld was too methodical to wander about adventurously, so he wanted to receive advice, and this is how he came into contact with Mac Carthy, who was to be his mentor, providing him with all the information he needed, and even an Israelite guide, Mordecai. He himself took on a Jewish name and Jewish costume. They set off across Morocco, a singularly reckless expedition, as no European had yet embarked on this presumptuous expedition. Foucauld soon realized that the timid Mordecai was not taking the initiative and that he himself had to make up for this deficiency. In fact, the dangers were real, and several times, as expected, they were attacked. One day, among others, Foucauld felt himself pulled back from his mount and hurled to the ground. He and Mordecai were robbed: for one night, he overheard his assailants discussing the advisability of letting their victims live. Freed, he continued on his way, not stopping to note down in a small notebook all his observations, geological, ethnological and even social; he questioned everyone, asking about customs, mores and the regions he crossed. He was also sensitive to the beauty of the sites, and his writing of his experiences (“Reconnaissance au Maroc”) is peppered with idyllic tales. He also had the good fortune to find unexpected help, and this was the miracle of his adventure, for which he would later praise God: unmasked by caïds (north African muslim tribal leaders) who had not been fooled about his true identity, he was protected; he would remain deeply grateful to his benefactors.

This trek brought him fame, to which he was quite insensitive. He had come to Africa in search of an activity, a risk that would free him from the tyranny of pleasure. “It is certain,” wrote a Benedictine monk from La Pierre-qui-Vire, “that the double lesson of the desert and of Islam at prayer contributed to opening the explorer’s soul to feelings of adoration that no longer knew how to spring forth, to cause him to get back in touch with his deepest life, to inescapably pose for him the problems of the Infinite, of the Eternal.” Truly, it is at this point that Foucauld was on his way to the final stage in his metamorphosis, where, in Victor Hugo’s words, “an immense Christ opens his arms to the human race” awaited him.

Conversion

Back in Paris, Foucauld took care of the printing of “Reconnaissance au Maroc”. However, the idea of religion haunts him. He had been seduced by Islamism, but admitted that it was not enough, that it could not withstand a little closer examination. He opened up to the woman who has been his “guardian angel” since childhood, a first cousin a few years older than him, Marie Montessier, now Mme. Olivier de Bondy. His spiritual affection for her never wavered. Mme. de Bondy was in contact with Abbé Huvelin, a former teacher of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, who gave popular lectures in Paris and was perhaps Littré’s lucky star. She arranged a few meetings with her cousin, who, ever anxious, was looking for an educated priest to solve the famous equation 1 = 3. In his library, Charles retrieved a book by Bossuet that had been given to him for his First Communion, and which offers an imaginative explanation of the Holy Trinity. He wandered the churches of Paris, spending long hours there, asking God to reveal Himself to his anguished soul. Finally, one morning in October 1886, he went to Abbé Huvelin’s confessional, confessed and approached the Holy Table. He found God because he was looking for Him …. Bourdaloue wrote: “To save ourselves according to the laws established by divine Providence, two conversions are necessary: God’s conversion and our own. God’s conversion to us, and our conversion to God. God must convert to us by attending to us through his grace; we must convert to God by faithfully following the movement of his grace.”

The Trappist

As Foucauld is converted, a new life began, but his director, Abbé Huvelin, wanted to test this reversal and advised a trip to Palestine. Foucauld obeyed, even though he was certain of the divine call. He decided to devote himself to God, “to do what was most perfect, whatever that might be.” Nazareth was his destination: he would join the Trappists. Foucauld declared that he was not cut out to imitate Christ in his public life, and added: “I had therefore to imitate the hidden life of the humble and poor worker of Nazareth.” He rejected the apostolate of preaching, which undoubtedly did not suit his nature of solitude and silence. Beyond that, Foucauld had not forgotten the Africa to which he was drawn, Morocco, which fascinated him. But, from then on, he would have to deploy his willpower at all times, for he knew that his jealous attachment to his independence was the moral core of his being, and this would be his profound struggle, subjecting all his outward acts to his obedience. He wrote to Mme. de Bondy six months after his entry into the monastery of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, in the Ardèche region of France: “I find it difficult to submit my sense, which will not surprise you.” Aware of this difficulty, he would often insist in his correspondence on his willingness to obey. In his daily life, he managed to bring himself into alignment with his goals, and it was with regret that the superior of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges saw him off to the monastery of Akbès in Asia Minor. This place of retreat is very poor, and this is an added attraction for him. Discipline was very strict, which was not to his displeasure. And there was the holy work of manual labor that Foucauld advocated, because it was a greater imitation of the life of Christ: he spent most of his day picking up stones and carrying them in baskets, or digging potatoes, a tiring task from which he took his rest by sweeping the chapel. Yet even this is not yet his ideal; he sought even greater abjection.

On Abbé Huvelin’s authorization, he left the Trappists, having been relieved of his vows by the Holy See. He went to Nazareth, where he hoped to be the last, “the most despised of men.” As a gardener with the Order of Saint Claire (the Poor Clares), the most servile and humble occupations were his daily lot; he ran errands in town, at the post office, and was happy when his beggar’s appearance attracted the laughter of street children, who went so far as to throw stones at him; he recounted this incident with joy to the convent superior. In his spare time, he went to the chapel and immersed himself in long prayer and meditation. For the abbess of Nazareth, as for the abbess of Jerusalem, to whom he was sent simply under the description of someone with a mission to be fulfilled, he was a singular enigma, all the more so as his appearance and gestures revealed a man who was no professional wretch. The intuition of these eminent women did not deceive them. This valet was out of place, and his true identity must be known. One day, all was revealed in a secret colloquy between Brother Charles and the nun through the gates that separate her from the world. The moment of this confession was the divine preparation for a new destiny long denied and delayed: the priesthood. Nazareth thus appeared in Brother Charles’ life as a crucial point, the end of a particularly enriching stage.

Béni Abbès

Ten years passed since the day the monastery door closed on Foucauld at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges. Now he was back in this place of prayer. He came here to prepare for the priesthood. On June 9, 1900, in Viviers, he was ordained a priest. He would not return to Palestine, which was overflowing with graces. Instead, he went to the most abandoned peoples: southern Algeria and the Sahara were calling him. Not only were the attraction and the solitude of the desert drawing him, but the call of souls who must be saved.

Béni Abbès was chosen, far beyond Figuig and Colomb-Béchar, on the edge of the Grand Erg, the sea of sand. Béni Abbès “is in the middle of a compact forest of six thousand palm trees watered by a beautiful foggara, and under which are beautiful gardens and many other fruit trees. The Saoura valley is about two to three kilometers wide here, with the oasis leaning against the left flank… The view of the valley, its two bends, the Hamada, the oasis and the ksar is admirable. The oasis, though only six or seven thousand palms, is very beautiful for the exceptional harmony of its shape, the good care of its gardens, its air of prosperity … and beyond this peaceful and fresh picture, we have the almost immense horizons of the Hamada getting lost in this beautiful sky of the Sahara which makes one think of infinity and of God–who is greater–Allah Akbar! In terms of climate, language and customs, Béni Abbès resembles Tissint, Tatta and Aqqa.” These three places were stopovers on his trip to Morocco, and he was happy to recall memories of them there.

At last, he was in the desert, isolated enough to enjoy his solitude, yet close enough to the village to be of service to whomever needed him. He fulfilled his vow of poverty, and of silence with God: “If it is sweet,” he wrote, “to be face to face with what one loves in the midst of silence, universal rest and the shadow that covers the earth, how sweet it is to go in these hours to enjoy the tête-à-tête with God! Hours of incomparable bliss, hours when all is silent, all is asleep, all is drowned in shadow, I live at the feet of God!” These hours of recollection brought him great joy. “Happy I am, for my Beloved is blessed, immutably blessed, and his happiness floods me with profound peace.” And he added: “But I would like to share my happiness with others”. In what way and to what extent?

One day, a soldier, astonished by the narrowness of his cell, pointed this out to him, and insisting, said: “But you don’t even have room to lie down.” “Was Jesus on the Cross lying down?” Foucauld replied with a smile. News of the presence of this curious roumi, and of the austerity of his life, quickly spread through the population, arousing curiosity, admiration, and then confidence. Charles de Jésus, as he would henceforth be called, was easy to talk to, which led to contact with everyone. Visitors, at first rare and shy, grew bolder and became beggars; Christ himself was always followed by beggars and solicitors. And what Foucauld wished for came true: his hermitage became the khaoua, i.e. the brotherhood, a dwelling where the door is always open, night and day. To one visitor, the marabou (a term for a holy man in north Africa) as he was called, would give food, to another a piece of cloth, and to still another a bit of money.

As for those who did not return, Charles de Jésus would try to find them, to get a grip on them, and so to pierce the armor of these timid souls. And so he worried, questioned and made resolutions: “We must,” he wrote, “live with the natives with the familiarity of Jesus with the apostles. Above all, to see Jesus in them, and consequently to treat them not only with equality and brotherhood, but with the humility, respect and devotion recommended by this law”. And so, day after day, he continued his apostolate through love, a free gift of friendship from which all notion of gratitude was banished.

There was no need to stay in Béni Abbès, any more than there had been in Nazareth, despite the deep peace of mind he felt there; he knew that his vocation was to live the hidden life of Christ in toil, austerity and solitude. On June 30, 1903, he wrote to Mgr. Guérin, his apostolic prefect: “Here, enough people, Muslims, have been exposed to Christian doctrine; souls of good will have all been able to come, all have been able to learn; all those who want to see, see that our religion is all peace and love, that it is profoundly different from theirs: theirs orders to kill, ours to love; I have no companion yet: Morocco is not opening up”. This dream of having companions never came true.

And furthermore, Béni Abbès was too happy a place for Foucauld, life became easy. No one was more affected by the physical geography of the sites than Fr. de Foucauld. He found in Saint John of the Cross, of whom he was a fervent reader, a phrase in keeping with his attitude: “It is advisable to choose the place that occupies the sense the least and makes it forgotten. For this, a solitary and even rough-looking place seems preferable to me… Mountains high above the earth are of this nature, usually devoid of vegetation and offering no sensitive interest.”

Moreover, Laperrine, an “incomparable friend”, wrote to Foucauld of his plans to tour to the extreme limits of the Sahara, insisting on the Hoggar; he even told him of the heroic exploit of a Targu woman from a noble family who, during the massacre of the Flatters mission, opposed the completion of the attack on the wounded whom she was treating in her tent, and had forbidden entrance to a bloodthirsty warrior chief.

Charles de Jésus confided his desire to go among the Tuareg (a nomadic people who lived mainly by raiding, who respected no natural laws) to his director, Abbé Huvelin. They were truly the “most abandoned sheep” who needed to be civilized and evangelized. Abbé Huvelin replied: “Follow your inner movement, go where the Spirit leads you. It will always be the solitary life wherever Jesus welcomes you into himself to give yourself to souls.”

He asked Mgr. Guérin for permission to go to the Tuareg, outlining his plan of activity in a place where “with solitude, I will have security, in order to learn the Targu language and prepare the translation into Targui of some books (it is the Holy Gospel that I would like to translate, into the Tuareg language and script)….” He would settle in a narrow cell where he would lead a solitary life, but without enclosure, striving to have “increasingly intimate relations with the Tuareg…, to travel in short days so as to chat along the journeys with the natives.” In addition, he would go “at least once a year to each of the posts, Adrar, In Salah, Timimoun, Béni Abbès and the others where there are Europeans.” This project, which Brother Charles de Jésus nevertheless placed under the sign of safety, was at first badly received by Mgr Guérin, who foresaw the difficulties of provisioning and the perhaps exaggerated importance of the services to be requested. Raising the question to a higher plane, he added: “God’s grace can easily overcome all obstacles; humility, however, and self-doubt urge us not to expose ourselves, without obvious inspiration from God, to situations requiring extraordinary graces: to act otherwise, to commit ourselves lightly in these situations would be to be rash and tempt Providence…”. However, at Charles de Jésus’ insistence, Mgr. Guérin granted the requested authorization.

Tamanrasset

Laperrine wanted to go as far as Timbuktu to build a bridge linking Algeria to French West Africa. He persuaded Charles de Foucauld to join his column when the time came, advising him to set up camp beforehand in Akabli, an ideal place to learn the Tuareg language, and to wait for him there. Fr. de Foucauld was overjoyed, for “the more I travel,” he wrote, “the more natives I will see, the more I will be known by them, and I hope to gain their friendship and trust”. Foucauld then went and waited in Akabli. Laperrine arrived three weeks later. Together, they headed south, but were unable to reach Timbuktu. Back in Béni Abbès, Brother Charles de Jésus replaced time spent on the manual labor he particularly respected with time spent pouring over copies of Tuareg texts that he made during his trek. He confessed that, being exhausted, he no longer intended to make further absences, that he wished to remain in the Brotherhood “which lacks only one thing: Brothers–in whose midst,” he said, “I can disappear into silence and solitude.” It was a passing lapse, for a few days later he received two urgent letters from Laperrine, offering to spend the summer in the Hoggar with Captain Dinaux. “I’m going to drop Foucauld in the Sahara,” Laperrine wrote to a friend. “He’s studying the Tuareg language, has medicine and two mehara (a kind of camel) to get around. You see, if the Count de Foucauld, this ex-explorer hussar and Trappist who has broken with the law, becomes chaplain to Moussa or someone like him, it won’t be a trivial matter.” Fr. de Foucauld eagerly accepted, as for him it was the will of God manifesting itself once again. He set off and arrived in Tamanrasset on August 13, 1905. Laperrine’s humorous hypothesis had become reality. But to ensure his friend’s safety, the “Saharist” decided to arrange a meeting between the missionary and Moussa Ag Amastane, chief of the Hoggar. The meeting took on a solemnity worthy of the Drap d’Or camp: oaths of protection were pronounced on both sides. Following this ceremony, Charles de Jésus settled in Tamanrasset.

And he went into the douar (arabian villages), entered the tents, spent long hours among the men, women and children, listened much, spoke little. He wanted to bring the benefits of our Christianity to these populations, but “it is well understood,” he wrote to his friend Fitz-James, “that in the hierarchy of values we must give first place to spiritual benefits, without omitting material benefits, because: 1. God formally orders us to do so; 2. material benefits contribute powerfully to the inner disposition of souls, and thus constitute a very real spiritual benefit.”

L’Assekrem

Brother Charles de Jésus learned that eighty kilometers from Tamanrasset, on the plateau known as Assekrem, there are other Tuareg of whom he would see very little, or perhaps not at all, because there were women, children and elderly people who did not leave the region. The Assekrem is almost two thousand eight hundred meters above sea level; that difficulty did not matter to Foucauld, who decided to build a second hermitage there: he felt that he must go wherever there are souls to be saved. He settled there, seeing many people when there was grazing available, and few people during the droughts. “This momentary solitude suits me,” he writes, “because it gives me all the time I need to work on my long-standing studies of the Targu language, which I’m anxious to complete.” He was thus alluding to a considerable undertaking, a work whose scope is a source of astonishment when one considers how much time his Touareg took up. It included no less than four dictionaries, as well as a collection of poems and proverbs, a collection of prose texts and a Targu grammar. However, he pressed on as far as his strength, which he felt was waning, would allow. On March 17, 1913, he wrote to Mme. de Bondy: “Don’t worry; I no longer have the strength to kill myself with work; when I go a little overboard, I see it right away and slow down; I give all I can, but it’s a far cry from what I used to give; besides, I’m so often interrupted by visitors that I have many unforeseen recreations.”

The life that he led in Béni Abbès, he would replicate in Tamanrasset and Assekrem: prayers, charity visits, linguistic work for those who would come after him as true missionaries, “to do all I can,” he wrote, “for the salvation of the infidel peoples of these lands in total forgetfulness of myself.” By his example, he won hearts.

The news of war reached him on September 3, 1914, and posed a distressing problem. But he was ordered to remain in the Hoggar, among these people, where his presence alone was perhaps the guarantee of their tranquillity. And in the midst of the general upheaval, he remained an advanced sentinel, with no other weapons than the love he felt for everyone, regarding them as brothers, and the gift he gave them of his whole self.

ON December 1st 1916, Fr. de Foucauld was alone in his bordj (an Arabic fortification) in Tamanrasset, busy with his correspondence, which he has never abandoned, in the belief that it was beneficial to all those to whom it is addressed.

To Louis Massignon: “We must never hesitate to ask for posts where danger, sacrifice and devotion are greatest: honor, we leave to whoever wants it, but danger and pain, we always ask for. As Christians, we must set an example of sacrifice and dedication.”

To Mme. de Bondy: “… Our self-annihilation is the most powerful means we have of uniting ourselves to Jesus and doing good to souls; this is what Saint John of the Cross repeats in almost every line; when we can suffer and love, we can do much, we can do as much as we can in this world. We feel that we suffer, we don’t always feel that we love, and that’s one more great suffering, but we know that we would like to love, and to want to love is to love…”

To his sister Mme. Raymond de Blic: “May the good Lord keep you all in good health until my return to France, after the victory … I have made great progress, but have not completed my little work on the Targuie language.”

The correspondence over, he began to pray. “Sacred Heart of Jesus, thank you for giving us this lesson, this clear example of what you want from us. Following your example, the example of your holy parents, your servant, your little brother must, at the first sign from you, fly, getting up at once, in the middle of the night, like Saint Joseph, fly to any journey, any flight, any exile; he must fly there in hunger, fatigue, cold, bad weather, the difficulties of the roads, dangers, destitution, all the difficulties, all the sufferings, like the Holy Family…”

A knock came at the door, and Fr. de Foucauld rushed to open it. Then occurs something dramatic: an assassination by the very men who were dearest to him among all.

“Think that you must die a martyr, stripped of everything, lying on the ground, unrecognizable, covered in blood and wounds, violently and painfully killed…”

Georges Gorrée

Bibliography

Geographical and Linguistic Works by Charles de Foucauld

RECONNAISSANCE AU MAROC Paris. Challamel. 1888 in-fol. 495 p. (101 dessins et 4 photos)

ATLAS Paris. Challamel. 1888. in-fol : 20 feuilles au 1/250.000e.

“VOCABULAIRE TOUAREG-FRANÇAIS DES NOMS PROPRES DE LIEUX ET DE TRIBUS (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar).” stencyl : 1907. 44 p.

EDITION REVISEE DE L’ESSAI DE GRAMMAIRE TOUAREGUE DE MOTYLNSKI. Alger 1908.

DICTIONNAIRE ABREGE TOUAREG-FRANÇAIS (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar) Alger. J. Carbonnel. Tome l 1919. 652 p. et tome II 1920. 783 p.

NOTES POUR SERVIR A UN ESSAI DE GRAMMAIRE TOUAREGUE (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar) Alger. J. Carbonnel. 1920. 172 p.

TEXTES TOUAREG EN PROSE (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar) Alger. J. Carbonnel. 1922. 239 p.

POESIES TOUAREGUES (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar) Paris. E. Leroux. Tome l 1925. 659 p. et tome II 1930. 462 p.

DICTIONNAIRE ABREGE TOUAREG-FRANÇAIS DES NOMS PROPRES (Dialecte de l’Ahaggar) Paris. Larose. 1940. 364p.

DICTIONNAIRE TOUAREG-FRANÇAIS Imprimerie Nationale de France. 1951. 4 tomes.

ECRITS SPIRlTUELS, préface de R. BAZIN

Paris de Gigord. 1924. 269 p.

DIRECTOIRE, introduction de L. MASSIGNON Paris. 1933. 145 p.

LE MODELE UNIQUE Marseille, Publiroc. 1935. 22 p.

L’EVANGILE PRESENTE AUX PAUVRES DU SAHARA Grenoble. Arthaud. 1947. 226 p.

VIE DE JESUS (textes d’Evangile) Grenoble. Arthaud. 1948. 160 p.

NOUVEAUX ECRITS SPIRITUELS, préface de P. Claudel Paris. Plon. 1950. 236 p.

PENSEES ET MAXIMES, introduction de G. Gorrée Paris. La Colombe. 1953. 96 p.

ŒUVRES SPIRITUELLES (Anthologie) Paris. Seuil. 1958. 832 p.

Correspondence

CH. de FOUCAULD LETTRES A HENRY DE CASTRIES

Paris. Grasset. 1938. 244 p.

CHARLES DE FOUCAULD ET MERE SAINTE MICHEL (lettres inédites).

Paris. Saint Paul. 1946

LES AMITIES SAHARIENNES DU PERE DE FOUCAULD. Lettres aux officiers publiées par G. Gorrée.

Grenoble. Arthaud. 2 vol. 1946. 406 et 506 p.

LETTRES A MONSEIGNEUR CARON

Paris. Bonne Presse. 1947.

LETTRES AU GENERAL LAPERRINE, introduction de G. Gorrée

Paris. La Colombe. 1955. 168 p.

ABBE HUVELIN, CORRESPONDANCE INEDITE présenté par J. F. Six

Tournai. Desclée 1957. 312 p.

LETTRES A MADAME DE BONDY, Introduction de G. Gorrée

Paris. Desclée de Brouwer. 1966. 256 p.

Principal Biographies

R. Bazin, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD, EXPLORATEUR DU MAROC, ERMITE DU SAHARA

Paris. Plon 1921. 488 p.

G. Gorrée, SUR LES TRACES DE CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

Dernière édition : Paris. La Colombe. 1953. 356 p.

Additional Biographies

P. Lesourd, LA VRAIE FIGURE DU PERE DE FOUCAULD

Paris. Flammarion. 1933. 286 p.

R. Pottier, LA VIE SAHARIENNE DU PERE DE FOUCAULD

Paris. Plon. 1939. 302 p.

J. Joergensen, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD (traduit du danois)

Paris, Beauchesne, 1941.

J. Vignaud, FRERE CHARLES OU LA VIE HEROIQUE DE CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

Paris. Albin Michel. 1943, 316 p.

P. Coudray, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

Alger. Chaise. 1949. 72 p.

M. Carrouges, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD, explorateur mystique

Paris. Cerf. 1954, 298 p.

P. Nord, LE PERE DE FOUCAULD, FRANÇAIS D’AFRIQUE

Paris. Fayard. 1957. 220 p.

J. Charbonneau, LA DESTINEE PARADOXALE DE CHARLES DE FOUCAULD Paris. Milieu du Monde. 1958. 192 p.

A. Merad, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD AU REGARD DE L’ISLAM

Lyon. Chalet. 1975. 135 p.

Spirituality Studies:

M. M. Vaussard, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD, MAITRE DE VIE INTERIEURE

Juvisy. Cerf. 1938. 237 p.

P. de Boissieu, LE PERE DE FOUCAULD Paris. Perrin. 1945. 256 p.

J. F. Six, ITINERAIRE SPIRITUEL DE CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

Paris. Seuil. 1958. 459 p.

Documents

G. Gorrée, CHARLES DE FOUCAULD INTIME, documents inédits

Paris. La Colombe. 1952. 176 p.

Album

CH. DE FOUCAULD ALBUM DU CENTENAIRE. Préface de Mgr MERCIER. Introduction de R. VOILLAUME. Textes et légendes de G. GORREE.

Lyon. Chalet. 1958. 208 p. 220 photos.

The “CAHIERS CHARLES DE FOUCAULD” collection comprises 44 illustrated volumes, published between 1946 and 1956. Founding director: Georges Gorrée. Editor-in-chief: Jean Charbonneau.

To our knowledge, in addition to the above-mentioned books, there are some 70 popular works and hundreds of articles devoted to Charles de Foucauld, in France and abroad. We apologize for not being able to mention them here, as it would go beyond the scope of this study.

This article, reprinted here with permission, is taken from Hommes et Destins: Dictionnaire biographique d’Outre-Mer, tome 2, volume 1, published in 1977 by the Académie des Sciences d’Outre-Mer (15, rue la Pérouse, 75116 Paris, France). All rights reserved. Translation by Luke B. Donner, DACB research assistant and doctoral student at Boston University’s Center for Global Christianity and Mission.