Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Ouandété, Louis

Pioneer couple in the Catholic evangelization of Ivory Coast

Pioneer couple in the Catholic evangelization of Ivory Coast

Louis Ouandété and Valérie Ama were among the very first Christian converts in the Catholic missions in present Ivory Coast. Louis was right hand man of the European missionaries due to his knowledge of the language, cultures, and environment of the interior, his homeland. For many years he accompanied both the near and the far-ranging missionary expeditions of the “fathers.”

The origins and tragic youth of Louis Ouandété

Ouandété (whose name means “who doesn’t know his father”) was born into the Djimini tribe near Dabakala, in what is today northeastern Ivory Coast, probably in 1877.

In 1894, when he was about seventeen years old, his village was attacked and pillaged by the forces of the Dioula conqueror Samory Toure. Their harvests were stolen, and the fugitive populations were pursued to be caught and sold as slaves in the markets of the region of Bouaké. His mother suffered this fate, but the young man managed to escape, and wandered aimlessly for several months in a country ravaged by war and reduced to famine. Like thousands of other refugees, he sought protection alongside the French troops who were retreating from the region with their numerous wounded, but the refugees slowed down the troops’ retreat, and the end result was disaster. The Samorian auxiliary forces attacked the rearguard of the retreating army, and picked off any isolated marchers. Ouandété was lucky to escape with his life, but he faced several more months of life as a refugee with no hope of returning to his homeland. When the army was assigned to other areas, the refugees were left in charge of the police in Grand-Bassam on the coast, and the Europeans in the city were invited to come and take charge of those they wished.

The first priests of the Society of African Missions (SMA), a Catholic missionary congregation, had arrived in what is today Ivory Coast in 1895, in Grand-Bassam, and in the following years founded several missions in the southern (coastal) region.

September 15, 1896: Fr. J. M. Bedel arrived in Ivory Coast, and two weeks later, September 27, 1896, he went with two of his more experienced confreres to the police station in search of twelve bambaras who could accompany them in a new foundation. From then on, the lives of Louis Ouandété and Fr. Bedel were intertwined. Fr. Bedel would be to him like a second father, the Christian faith would transform his life, and for thirty years they would work together in the evangelization of the country. The very next day the twelve young refugees left for Dabou in the company of Frs. Hamard and Bedel. There they would found a mission, an agricultural orphanage, and take charge of a school which they created. Ouandété aided in the construction of buildings and helped plant the first coffee and cacao plantations of the region.

However, he didn’t stay at that mission for long; he was one of the three “boys” of the Bassam mission, and it was there that he attended Fr. Ray in his last hours, and cared for his companions in the terrible yellow fever epidemic which struck the capital in 1899. The Europeans were dispersed, and as a sanitary measure, all contact with the infected was prohibited. Ouandété was the only one assisting the three priests who died in the mission or in the city hospital. He even risked his life helping Fr. Pellet save the safe-box of the mission with its important documents when their house and others were burned down as a “sanitary measure,” on May 17, 1899. After this catastrophe, since the mission was empty, he rejoined Fr. Bedel in Bonoua, who for the last two years had been in charge of that parish. On Christmas day in 1899, aged about twenty-two years old, Ouandété was baptized in Bassam and given the name “Louis.”

Return to the north

At the end of 1901, Fr. Hamard, the new “father prefect” of the SMA, chose Fr. Bedel to undertake an exploratory journey to the northern part of the country with a view to investigating a favorable location for a missionary foundation. He was allowed to choose his traveling companions, and he chose Fr. Fer and Louis Ouandété who, it was thought, might be a good guide toward the northern regions which were his homeland. This choice proved to be an enlightened one, and the servant showed himself to be trustworthy before also becoming a friend.

Their departure date was January 13, 1902. For the missionaries it was an expedition into the unknown; for Ouandété, it was a return to his native land, which had been freed of servitude to Samory since 1898. He also had hopes of receiving news of his loved ones. They passed through the Baoulé country under military administration. Louis was the headman of the porters, and showed himself an able hunter, able to provide the small expedition with fresh meat. They arrived in Bouaké on [February] 7. Fr. Fer, tired out and ill, stayed on to oversee the construction of a modest house, while Fr. Bedel and Ouandété continued the trip alone. On March 7 they took to the road at a rapid pace; they earned the reputation among the locals of being untiring walkers. They did a tour of various villages in the present diocese of Korhogo, returning in a marathon twenty-nine hour trek, and arriving in Bouaké Good Friday morning, March 28, 1902. After Easter they took to the road again, heading south, then shortly afterwards they took a different long route to the north, bringing provision. By mid year (June 23rd) they were back in Bassam, having covered 1,600 km on foot in six months!

Marriage to Valérie Ama

During a respite from their travels in the north, Louis Ouandété married Marie Valérie Ama on August 18, 1902, at Dabou. The marriage was witnessed by Fr. J. Moury, in the presence of the Apostolic Prefect Hamard, who wished thus to testify to his affection for the young couple, and especially for Louis, whom he knew well.

Our knowledge of Marie Valérie’s origins comes principally from a letter of Fr. Hamard, of which we offer the translation here:

In the Sarwi, a young girl who was held captive by an influential personage among his numerous slaves, was lucky to become aware that her master had destined her to be sacrificed during an upcoming feast. She managed to escape, and sought refuge with a European woman to whom she confided her story and the fate that awaited her, and besought her to have pity on her and save her life. The brave woman took her in, and sometime later sent her to the sisters of Dabou. Ama, the happy liberated slave, received from the sisters, her adoptive mothers, the blessing of the faith. I personally had the sweet consolation of administering Holy Baptism to her, and of preparing her for her first Communion, which she made with a truly admirable fervor. She is now married with one of our best Christians, a former slave of Samory, and mother of three beautiful little black children, of whom the eldest knows very well how to invoke the Good God and the Holy Virgin.

It seems that she was born about 1883, at Krinjabo. According to the testimonies of Frs. Hamard and Moury, she was a slave of a wealthy businessman who either maltreated her, or destined her to be a funerary sacrifice (the texts are in disagreement on this point); what is clear is that she escaped and sought refuge in the house of a European woman in Assinie, on the coast. The woman and her husband treated her well, and wanted to emancipate her, but her former master demanded that she return to Krinjabo. She was given a letter of recommendation and safe passage to the fathers’ mission in Bassam, and somehow walked alone the 80 km to the mission. Precisely about this time [end of 1899], after the yellow fever epidemic, the sisters of Memmi had been transferred to Dabou. A sister who was leaving that very day by steamer to join the other sisters was given the charge of taking with her the young girl. Her former master made some attempts to take her back, but she refused to leave the sisters, to whom she owed her formation in the faith and her domestic instruction.

Louis Ouandété had been working for the sisters since their installation at Dabou, so he had good opportunity to get to know Valérie during the two years when their similar lives were closely related.

She received baptism from Fr. Moury, made her first communion April 13, 1902, and was confirmed a month later by the Apostolic Prefect, Fr. Hamard. As soon as Louis returned from his journeys in the north, Louis asked to marry her. It was not a marriage arranged by the fathers or the sisters, and Fr. Hamard is very clear on that point. However, he expressed his opinion that they would be “a model for Christian families in the future freedom village of Fr. Bedel.”

Missionary couple

Shortly after their marriage in August of 1902, Louis and Valérie became a missionary couple, establishing themselves alongside the priests in a mission compound in the north, taking increasing responsibility in overseeing various apostolates.

In December of 1902, Louis and Valérie accompanied an expedition of SMA fathers to the northern region to establish a mission there. They settled in Guiembé, where the chief had welcomed the visitors the previous year. The couple hurriedly cultivated a plot to feed the small company and the personnel of the school which they planned to build. However, further expeditions made it clear that the projected village should be located rather in the key village of Korhogo. Fr. Bedel returned to Dabou to bring the necessary materials for the definitive establishment of the mission, and in early January of 1904, two SMA fathers travelled to Korhogo. Louis and Valérie remained at Guiembé to take care of the first northern mission. Valérie is recorded as the godmother of the first person baptized in Korhogo, an old man from Guiembé, named… Valerien! While Fr. Bedel began the freedom village named Wallonville on the outskirts of Korhogo, the couple stayed where they were located for a few more years, helping to orient liberated slaves and young northerners who wished to attach themselves to the mission.

The couple lived in Wallonville until 1918. God blessed the new family with two sons: Jean-Marie (born 1904) and Philippe (born 1906). The hamlet had been destined at first for the reception of former slaves uprooted from their cultures and places of origin, but soon became the cultural center of the mission, the retreat house and welcome center for the first Christians. Louis accompanied various missionaries to the outstations. Almost every morning the family would go up to the village of Korhogo for mass, and in the evening, after work in the fields, would gather again for the recitation of the rosary. When he was present, Louis would preside at the evening prayers.

On August 15, 1911, seven year old Jean-Marie made his first communion, benefitting from the recent dispositions of Pope Pius X, who lowered the minimum age for reception of the sacrament by children. Up until the outbreak of World War I, Louis continued to be the missionaries’ guide. He was also a companion to the new priests who came to supplement the personnel of the new Apostolic Prefecture of Korhogo.

The “Great War” of 1914–1918 affected even the mission stations in Western Africa. Even the church personnel were mobilized: Fr. Bedel had just enough time to perform a few baptisms and to give over responsibility for the mission to Louis Ouandété before his incorporation into the “Senegalese Shooters” in Bouaké. Although he was the closest stationed missionary, he was not able to obtain permission to make pastoral visits to the newly founded and still fragile Christian communities. So, twenty Christians, led by Louis and Valérie, went on foot to Bouaké (230 km!) in April of 1916, in order to make their Easter communion. However, in June of that same year, Fr. Bedel was transferred to the military hospital in Bordeaux. Ouandété thenceforth was alone at the head of the Christian community until July of 1917. At that time Fr. Bedel was allowed to return to the region, pending a possible new mobilization, but soon the war was over. After the armistice a few new priests also arrived.

After the war, Fr. Bedel was transferred, and Mgr. Diss, the new Apostolic Prefect, took over. The Ouandétés moved to the village of Korhogo itself, and their boys began to take charge of the cultivated fields of Wallonville. The uprooted former slaves were gradually repatriated to their places of origin, and the Anti-Slavery Society which had sponsored the founding of the freedom villages had been disbanded during the war in order to attend to other urgent needs. As Louis and Valérie’s children grew and married, new members were added to their family.

Louis Ouandété, builder

In 1923, Louis was put in charge of the hurried construction of the village church on a new piece of land (made urgent due to legal complications), and he showed himself a very capable master builder, bricklayer, mason, carpenter, and thatched-roofer. He was often on call in the future for the construction of, or repairs on, the mission buildings, and his grand-children proudly possess a wooden door that he made!

The new Apostolic Prefect, Mgr. Diss, began a radical change in the pastoral policies of the Catholic missions in his jurisdiction. He decided to apply the methods that had proven effective in the south: an apostolate of presence and of personal contacts. First, after categorically abandoning every project of “Christian village,” the mission was brought toward the center of the village, and schools were begun again. Fr. Vion turned out to be the man for the job: he loved the youth, he began a beneficent society, and he used films in his apostolate as he visited various village outstations. Every available evening, accompanied by Louis Ouandété, either Mgr. Diss or Fr. Vion would go out to greet the people in their homes: the Christians, certainly, but also the chief and the elders. They would especially visit villages that had been pastorally neglected in the early post-war years. Their trips would last several days, because the idea was that “it’s necessary to live in the midst of the people, and that requires a more prolonged presence.” So Louis would leave on foot, or more and more often, on bicycle, taking advantage of the network of pathways connecting the larger villages.

Louis was a voluntary (non-paid) catechist, because from the very beginning of his service, he had independent means of supporting his family: in addition to the cultivation of his own fields, he engaged in other productive activities such as hunting and raising pigs. He worked as a carpenter and mason, either for his family’s needs or for others, and in order to be prepared for unforeseen needs, he had a herd of cattle. His was a firm and conscious intention never to “eat up the money of the priests.”

Catechist

What were his catechetical methods? Obviously, those of the time, although applied with great flexibility. As in all the apostolic vicariates of Ivory Coast, one used a question-and-answer catechism of the type that was current in French dioceses. However, the quality of evangelization in each case depended more upon the catechist than upon the materials used. Louis’ catechesis was vibrant and concrete, with the points illustrated by examples taken from his rich experience of everyday life. He was known to be a good story-teller, and “during his encounters with the catechumens, nobody nodded off!”

In those days liturgical chant, at least in terms of the vernacular languages, was still nascent, except for a few songs in honor of the Blessed Sacrament and even fewer songs to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The melodies were either Latin or Alsatian, and the repertoire was soon exhausted. If there were few vernacular songs, there was abundant expression in prayer: all the Christian families would gather for the recitation of the rosary each evening, led by the Ouandété family.

Louis had a particular concern to encourage the dispersed Christians who were living alone or in small numbers in the midst of an adverse cultural situation. He was confronted with many questions concerning the first inculturation of the faith: how to observe Sunday rest in village life, abstention from the traditional sacrifices without unduly alienating one’s family, how to have a Christian marriage in a pagan village, etc. Louis had to give answers to such questions, answers that could not be found in any existing catechism, and he did so with great prudence and discernment.

The Prefect Apostolic wanted to extend pastoral network into the west of his territory, so Louis, who was “as much a missionary as the rest of us,” was once again called upon to accompany the missionary trek. Mgr. Diss and Fr. Vion went on bicycles part of the way, and partly on foot. The expedition left at the end of February 1924, and covered 1170 km in forty-one days!

Mission auxiliary

At the end of 1924, the aged (seventy-one year old) Fr. Bonhomme, whom Louis had known in his earliest years with the SMA fathers, arrived in the prefecture to supply reinforcements for one of the under-manned missions. But before he left Korhogo for the mission station of Ferké, he witnessed an unusual convocation of Christians, customary leaders, and political authorities of Korhogo on February 8, 1925. The occasion: a public homage to Louis Ouandété upon conferral of the medal “Bene Merenti” conceded to him by Pope Pius XI. Monsignor Diss lauded him on the occasion in the following words: "This indefatigable helper of the missionaries could well rest a bit, because his habits of work and economy have given him a comfortable life-style, but he has not diminished his active life in the least, because he has promised to devote himself to the service of the Mission until death."

In fact, the time for his retirement had not yet arrived: during a personnel crunch in the prefecture, the newly arrived Fr. Wolff was left alone in Korhogo with the school and the village outstations under his care. Although he would only stay there about two years (1927–1929), this priest made a particularly favorable impression upon the Christians in the region, who would long afterward remember him by name. Each evening, led by Louis Ouandété, he would head out to the “bush” to visit families, perched upon his rusty bicycle. Repaired with metal bands in crucial spots, it had long since lost its bell and half its spokes. However the clattering of the scrap-metal spare parts announced his arrival perfectly well without the bell, and the women coming from the market would line up single-file along the path, well aware of who was coming before they even turned around, and joyful laughter would accompany their greetings to the catechist as he passed.

When a new priest, Fr. Steck, arrived at the mission in 1929 to replace Fr. Wolff, his hard-nosed employment policies alienated several of the workers, who chose to leave. Louis adapted himself to the new style, judging it also a worthy, if stricter manner of conducting affairs. In those years of economic crisis, the Ouandétés counted on their own labor to survive. Louis had no problems with that, nor any lack of courage in facing the future. The mission in those years initiated a veritable industry of pig husbandry, and the countrywide reputation of Korhogo pork was established.

In the 1930s a succession of young priests arrived in Korhogo, and they generally stayed only for a short time. Louis oriented them to the Senufo cultural world, was their companion on trips, and acted as their interpreter. When he saw the need to correct a newly arrived priest, he would always find a way to say something to the young missionary discretely and in private, thus avoiding problems with the other Christians or problems for the new arrival among the “fathers.”

At the end of 1938, Mgr. Diss resigned from the pastoral task of apostolic prefect, and Fr. Wolff was named to replace him (March 1939), only to die of exhaustion five months later. A little earlier, Fr. Vion had also passed away, Fr. Steck had been reassigned from Korhogo to Kouto, and on top of it all, Louis was “retired” from his position as general auxiliary of the missionaries in Korhogo. However, Louis was not one to rest on his laurels and take his ease: “I’ll have plenty of time to rest when I come before the Good God.” He continued to oversee his animal husbandry projects, and still did a bit of carpentry for his family’s needs or for pleasure. On the other hand, he gave over full responsibility for his fields to his two sons Jean-Marie and Philippe. They also were financially independent: living from agriculture and hunting, they were, like their father, voluntary catechists.

Valérie was a woman blessed with good sense. Every day she would sell her alokos (fried bananas) in a corner of the market, near the stores. The old-timers of Korhogo recall seeing her there in sunshine or rain, under the protection of a large red umbrella. She knew everyone, both the natives of the area and those from other regions. Her distant origin led her to become, at least in the Christian community, a virtual bond of unity among the parishioners of different origins. Among the Christian women she had a role as a counselor and organizer. She rendered multiple services to the mission: it was for her an honor to provide the Fathers’ meals on Friday (day of abstinence), and she arranged to have harvested and sold, without seeking to make a profit, the mangos from the trees of the Mission compound.

Every morning, the couple would attend mass if the priest assigned to the mission was not out on a pastoral visit. If the altar boys were missing, Louis felt honored to serve mass. They were both daily communicants in a time when it was not the usual practice. In the evenings they were present for benediction of the Blessed Sacrament and the rosary. Every Saturday evening they would go to confession. Louis was very happy that he could continue in his function of translator, interpreting the Gospel and homily for the congregation on Sundays and feast-days.

If in his old age Louis no longer led expeditions through the bush, he still exercised other functions for which his authority and his reputation were indispensable. He became the leader of the Christian community. The traditional leaders of Korhogo often called upon him to support their initiatives vis-à-vis the colonial administration, and he was also the official representative of the Christians in their relationships with the traditional elders and the Muslims. People sought him out to help with marital problems, particularly but not exclusively the Christians. His influence was such that he was able to solve felicitously many cases of young Christian girls promised in marriage to (often elderly) non-Christian men. A lot of tact was needed in these cases, so that the ex-husband-to-be would not lose face. One of the ways of dealing with these delicate situations was to send the young woman to Louis, who could then act as one who “arranged marriages.” He would then be able to give her over to the man of her choice.

The difficult years

The period of Fr. Nonnemacher’s ministry at Korhogo (1939–1945) coincides exactly with the years of the Second World War. The atmosphere in Korhogo was troubled: there were many restrictions, and beyond that, hidden struggles between factions of the European population, which had divided political loyalties. There was even distrust among the missionaries. Nevertheless, there was also the joy of new laws which permitted private Catholic schools. The Korhogo Mission School was officially recognized Aug 28, 1940, and would play a role in the renewal of catechetical staff in the prefecture.

In 1941, the Ouandété family was plunged into sorrow by the death of their second son, Philippe, who died May 1, 1941, aged only thirty-five years! At some point during the years of World War II, Fr. Bedel returned from Togo to spend a week in Korhogo, to the great joy of the Ouandété family. He wanted to spend his last days in Korhogo, but died instead in Abidjan, December 14, 1943.

Once again, with the armistice which ended the war, the priests assigned to Korhogo changed. Two new priests who arrived in the years immediately following the war undertook the building of a new presbytery, and then of a new church on the current mission compound which had been allotted to them.

Louis Ouandété, witness of an epoch

Right after the war, Louis came out of his active retirement to make one last trip to the southern regions of the country, to celebrate with the Ivorian Church fifty years of Catholic evangelization of the country. He accompanied Fr. Guerin, who had been invited to celebrate the occasion on October 10, 1945. It turned out that he and Fr. Meraud were the only living representatives of the first years of evangelization. They were presented to those attending as the witnesses of those heroic days. Louis reminisced about “those days” with modesty and humor: he recalled carrying Fr. Meraud’s suitcases when he first arrived! Several days later, he was invited to speak to the sisters at Moossou, and he made this prophetic statement reported by Sr. Generosa: “We worked very hard without seeing the results, but when I will be before God, there will be many Christians in Korhogo.”

One could say that the principal trial of the Ouandété couple was to see their loved ones depart from their presence: their eldest son, Jean-Marie, also died in his mature years, on March 2, 1946.

They continued their lives of service, amidst joys and sorrows. The national climate after the war was turbulent: political parties and the colonial administration sparred over various issues. The Ouandétés looked on ruefully from afar, as if citizens of another world.

Death of the two spouses

When Valérie was approaching death, the two spouses took the opportunity to forgive each other for any offenses they may have caused each to the other. Then Louis said: “Go in peace, Valérie, my wife. Our children have left before us, and now it’s your turn. It is the Lord who will receive you. If you see our children before our Heavenly Father, please come and seek me out, so that I may receive from Christ the reward promised to his servant.” Mgr. Durrheimer, the new apostolic prefect, personally presided over her burial (December 18, 1948).

From that moment on, Louis seemed not to be of this earth; he was preparing for his own passing. The mission had care of a large part of his liquid assets, so he indicated to Frs. Fellman (pastor) and Paulus (executor of his will) his last wishes. A part of his money was to be destined to insure a pension at the sisters’ convent for his three unmarried grand-daughters; another portion was to be given for finishing the church of Ferké (then under construction), and the rest would return to the Mission of Korhogo for its needs and for mass intentions for his family. Fr. Paulus agreed to be responsible for seeing that 1,000 Francs would be given to his married granddaughters. He also gave a sum to the younger sister of Louis, who arrived in the village after the announcement of his death.

Louis had tired himself out overseeing the work of redoing the thatched roof of the church (his specialty). He no longer went up on the roof, but directed things from down below. He developed a severe bronchitis which besieged him for an entire month. The Sunday before he died, he paid his last visit to the mission. On that Tuesday morning, March 2, 1949, Fr. Fellman, who came to bring him Communion, was surprised to find him dressed in his feast-day best, wearing the medal he had received in 1925. He knelt to receive Communion, and prayed in silence for a moment with the priest. He returned to his bed with difficulty, and gave up his soul at 5 p.m. that afternoon. The news of his death caused great emotion in the village, and his burial, presided by Fr. Steck (who came down from Kouto for the service), gathered together Christians, Muslims, and the traditional leaders to give a well-deserved homage to a man whom all recognized as exceptional.

We finish with this testimony of Mgr. Wach, who knew him well: "I am convinced that divine Providence brought together Louis Ouandété and Fr. Bedel in order to confide to them the task of implanting the Church of God in Korhogo. They fulfilled that task with the energy and devotion which we well know. Without fear and without reproach, Louis, the intrepid defender of the Church, is a sort of John the Baptist of Korhogo."

The fruits of the missionary work of the Ouandété couple

In April of 2005 the diocese of Korhogo celebrated its centenary, rendering homage to Père Bedel and to Louis and Valérie Ouandété, the pioneer catechist couple who worked with and accompanied him. At the time of that anniversary, thousands of Christians in Korhogo were living out their Catholic faith despite the war and the difficulties being experienced in that part of the country.

Thomas Kevin Kraft

Bibliography

All of the information in this biographical summary is taken from the booklet by Fr. Pierre Boutin, Aux origines de l’Église de KORHOGO, un couple: Louis Ouandété et Valérie Ama [A Couple at the origin of the Church in Korhogo: Louis Ouandété and Valérie Ama], Korhogo: Conférence Épiscopale de Côte d’Ivoire, 1994.

I believe that Fr. Pierre Boutin is still in Korhogo. He has an e-mail address: [email protected].

This story, received in 2012, was contributed by Fr. Thomas Kevin Kraft O.P., Roman Catholic priest, member of the Order of Preachers (Dominican Friars), and Lecturer at Tangaza College (Nairobi, Kenya).

Photos

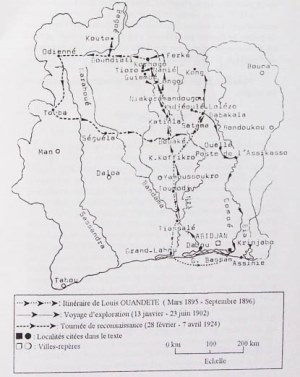

- This map shows Louis Ouandété’s refugee itinerary, the early SMA missionary journeys to the north of the country, and the villages and mission stations mentioned in this document.

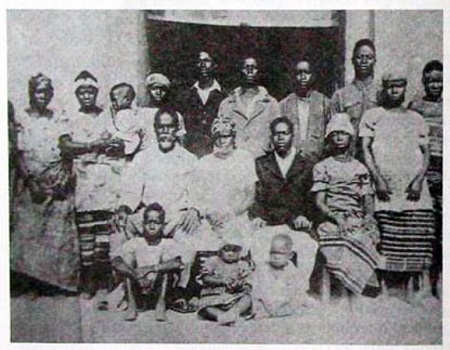

- The Ouandété clan (Louis and Valerie are at the left and right ends of the middle row – seated), surrounded by their children, their spouses, and in front, their grandchildren. Date unknown.

- Ouandete Louis