Capitein, Jacobus (C)

Early life and education in the Netherlands

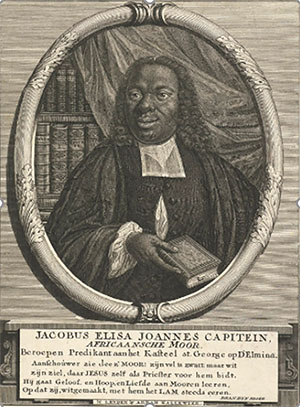

Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein was an African-born Dutch Reformed minister and missionary. [1]

Of Fante ethnicity, Capitein was born around 1717 on the African Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). In 1725, at the age of seven or eight, he was bought as a slave by a Dutch slave trader Arnold Steenhart, who gave Capitein as a present to his friend Jacob van Goch, a Dutch West India Company merchant. [2] In 1728, at the age of eleven, Van Goch took Capitein with him to the Netherlands, where Capitein automatically gained his freedom, since slavery was illegal in Netherlands, though not in the Dutch colonies. With Van Goch as his guardian, Capitein settled in The Hague, and lived there for nine years between the ages of eleven and twenty.

In The Hague Capitein learned the Heidelberg Catechism and was baptized. When in one of these catechism classes Capitein expressed his wish to study theology in order to become a missionary to his own people in Africa, the news soon spread to Rev. Hendrik Velse, a firm advocate of missions, who convinced Van Goch to allow Capitein to attend school. With Van Goch funding his studies, Capitein enrolled and spent six and a half years at the Latin School in The Hague, and finished his studies there with a treatise entitled De Vocatione Ethnicorum (“On the calling of the heathens”), corresponding to his desire to become a missionary. [3]

In 1737, at the age of twenty, Capitein left The Hague and moved to Leiden, where a number of benefactors made it possible for him to study theology at the famous university there. He completed his studies at Leiden in 1742 with a Latin dissertation entitled Dissertatio Politico-Theologica de Servitute, Libertati Christianae non contraria (“Political-Theological Dissertation concerning Slavery as not in conflict with Christian Liberty”), which was also published in Dutch translation. [4] Based on biblical-theological, legal, and historical sources and considerations, Capitein’s argument was that bodily servitude is compatible with Christian liberty (understood to be of a purely spiritual nature), and that therefore it was lawful for a Christian to own a slave or for a Christian to be a slave, and unnecessary for slaves to be manumitted upon their conversion to Christianity. The primary goal of Capitein’s dissertation was therefore to prove that Christian missionary work—and thus his own prospective work as a colonial chaplain and missionary under the auspices of the Dutch West India Company—would not threaten the institution of slavery. [5]

Having completed his theological studies at Leiden after a little more than four and a half years, Capitein became eligible for ordination in the Dutch Reformed Church and was now one step closer to his goal of becoming a colonial missionary at Elmina, the Dutch headquarters on the Gold Coast. In order for his ordination to take place, he had to gain the approval of the Classis of Amsterdam, which was in charge of appointing ministers in the Dutch colonies, as well as the approval of the Dutch West India Company, which owned the Elmina Castle, where Capitein would live and serve. Moreover, it was the trading companies (the Dutch East and West India companies)—not the Church—who paid the salaries of ministers and missionaries in the colonies, and therefore all Dutch colonial ministers and missionaries were employees of the trading companies. This meant that the trading companies had great authority in the Classis of Amsterdam’s appointment of colonial ministers and missionaries, as well as in the activities of colonial ministers. Capitein’s approval from both the ecclesiastical and Dutch West India Company authorities came promptly, however, and he was ordained as a minister and missionary in the Dutch Reformed Church on May 7, 1742, and thereby became the very first native African to be ordained in a Protestant church. [6]

Return to Africa as a colonial chaplain and missionary

Not long after his ordination, after having spent fourteen years in the Netherlands in the crucially formative years between the age of eleven and twenty-five, Capitein in 1742 made the three-month journey by ship back to the African Gold Coast, where he stayed at the Elmina Castle, the fort of the Dutch West India Company. Despite his inaugural sermon in Elmina [7] enjoying a favourable reception, his arrival in Elmina marked the commencement of what would prove to be the final four and a half years of his life, a time which would be marked by numerous troubles. Capitein’s ministerial duties in Elmina would be twofold: he was both a chaplain to the Europeans at Elmina Castle as well as a missionary to the native Africans.

Chaplaincy to the colonial Dutch

Capitein’s chaplaincy entailed the revitalisation of religion among the Dutch living in Elmina, which had stalled prior to his arrival due to the regular unavailability of colonial chaplains as well as several other factors which hindered the vivacity of Christianity on the Gold Coast. After his inauguration as colonial chaplain, Capitein encountered a number of difficulties and hindrances to his ministry among the Dutch.

Chapel attendance among the Europeans tended to be low, with a regular membership of only seventeen people. Most of the 241 Europeans on the Gold Coast at the time, of which 107 were based at Elmina Castle, were Roman Catholic or Lutheran, and even among the Dutch Reformed minority chapel attendance was very low, with most being rather indifferent to religion. In addition, the Dutch West India Company staff often relocated, while both of his appointed elders died in quick succession. Capitein’s congregation was therefore in a constant state of flux. Furthermore, besides the low chapel attendance, the congregation was in such a poor state that it did not even have elders, and therefore Capitein had had to organize a church council from scratch. [8]

Although Capitein tried to revitalize the celebration of the sacraments and particularly the Lord’s Supper, which had been dormant for some time before his arrival, yet he soon came to feel uncomfortable about doing so. This was primarily because several members of the congregation were cohabiting with native African or Tapoejer (i.e. mulatto) women, which was a common practice in the Dutch colonies at the time. [9] Capitein felt that these members would be disqualified from partaking in the Lord’s Supper as long as they remained unrepentant about this cohabitation, since in his judgment they could not receive the sacrament with a good conscience, and admitting such persons to the Lord’s Supper would mean “calling down [God’s] wrath on the whole congregation.” [10] Capitein’s catechism classes, which were held during the week were also poorly attended, since not only were there very few Reformed Christians among the Europeans at Elmina, but these were also too preoccupied with daily activities to attend. [11]

Besides the difficulties already mentioned, Capitein’s ministry to the Dutch at Elmina was hindered by the negative attitude of the colonists towards him. The Dutch at Elmina were generally averse to having an African set over them as their spiritual leader, and Capitein’s criticism of the general immorality among the Europeans—particularly the aforementioned practice of cohabitation with native and mulatto women—made him an unpopular figure. He was thus seen as an African interfering with the private affairs of Europeans, who lived by the adage that “there are no Ten Commandments south of the Equator.” [12] As a whole, therefore, Capitein’s ministry to the Dutch colonists at Elmina was a rather troublesome, frustrating, and disappointing one.

Missionary work among the native Africans

The second part of Capitein’s colonial ministry was his missionary work in relation to the native Africans, which, of course, was the primary reason why he wanted to study theology in the first place, and a major reason why he desired to return to his native African Gold Coast. Despite his African ethnicity, Capitein’s fourteen formative years in the Netherlands meant that he had to find a way to reintegrate with the natives of Elmina. His conspicuous European language, dress, manners, and obvious links to Elmina Castle made it clear to the locals that he was different to them. Whether Capitein remembered the local language, Fante, from his childhood, or whether he had to learn it anew after such a long time in the Netherlands, is unknown to us. Regardless, Capitein regarded it as essential for a missionary to communicate with the natives in their own language. [13]

Capitein considered it important to marry a native woman to help him integrate more easily into the African community, a desire he expressed in his letter to the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam in February 1743. [14] The problem, however, was that according to Dutch law a Christian could only marry another Christian. The girl Capitein had in mind therefore first had to be instructed in the Christian religion and baptized before such a marriage was possible. Capitein himself could not take up the task for reasons of propriety, as it would have stirred up rumours if the girl was seen frequently attending his classes, and no one else could be found who was up to the task of instructing a potential wife for Capitein in the Christian religion. It was consequently suggested to him that the girl be sent to the Netherlands to be educated there, but her parents did not consent. [15] The Classis of Amsterdam also rejected Capitein’s proposal of having an African girl sent to the Netherlands to be instructed in the Christian religion, and instead, without any prior notice to Capitein, they sent a young Dutch woman—Antonia Ginderdros from The Hague—to Elmina to become Capitein’s wife. [16]

Evangelism through education

Capitein aimed to evangelize the natives primarily through education, and soon after his arrival in Elmina he started his work on a school. Capitein’s goal was to reach the African adults with the Gospel by educating their children. Not only were the children regarded as being able to more easily influence their parents, but also, by focusing on the children, Capitein endeavoured to establish an indigenous church with greater longevity as part of his long-term objectives. [17] When Capitein started teaching at the school, there were about eighteen to twenty children in attendance, a number he endeavoured to increase. Within five months after his arrival, Capitein had taught these children basic spelling and grammar, most of them could already recite the Lord’s Prayer by heart, and they had moved on to learning the Apostles’ Creed and the Ten Commandments. Any newcomers were first taught the alphabet before they could make any further progress. Capitein noted that it was difficult to attract other children to school, as they were unaccustomed to receive any formal education, prone to spending their time in play, and their parents were generally reluctant to send them to school. [18] This was particularly the case with girls, whose parents realized that, if their daughters received instruction in the Christian religion, then these daughters would no longer be willing to cohabit with European men. [19] Cohabitation must therefore have presented economic or other benefits to the native families, which they were reluctant to relinquish. In due course, however, Capitein did manage to increase the school attendance from twenty to forty-five. [20]

Translation work

Capitein also attempted to reach his fellow Africans through translation work. Within a year of his arrival, he had translated the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Ten Commandments into Fante, and these translations were sent back to the Netherlands and published in Leiden in 1744. [21] The Dutch West India Company authorities and the publishers, though expressing appreciation for Capitein’s translation efforts, nevertheless questioned parts of his translations. Capitein’s Fante translations were accompanied by a literal rendering back into Dutch, which allowed the authorities, who of course did not know Fante, to follow his translation. The publishers especially took exception with Capitein’s translation of the fourth commandment, in which Capitein omitted the prohibition of a servant (dienstknegt) working on the Sabbath. The publishers added this clause to Capitein’s translation in brackets. [22] While the publishers gave some of Capitein’s translations the benefit of the doubt by acknowledging that some Dutch words do not have exact equivalents in Fante and therefore had to be substituted by approximate equivalents, they questioned Capitein’s omission of servants in the fourth commandment because he did include servants in his translation of the tenth commandment. [23] Therefore this omission was not due to Fante not having a word meaning “servant.” While we cannot claim this with absolute certainty, it does seem as though Capitein deliberately omitted servants from his translation of the fourth commandment, probably from the fear that, upon learning that they were exempted from working on Sundays, Christian slaves would use it to demand a day of rest from their masters. [24]

Discouragements and hindrances to missionary work

Capitein’s missionary work to the Africans was hindered by several other factors. Two schoolmasters who worked alongside him at the school died in quick succession, and a third returned to the Netherlands after less than a year, and so Capitein faced a struggle to keep teaching colleagues at the school. [25] Another important factor is that, from 1739 to 1740, only two years before Capitein’s arrival in Elmina, there was open armed conflict between the natives of Elmina and the Dutch colonists. [26] The natives of Elmina thus could not have done otherwise but to hold a measure of resentment or suspicion towards the Dutch West India Company and anyone related to it. Capitein’s obvious affiliation to the Dutch West India Company would therefore have been an obstacle to his missionary work among his fellow Africans.

Capitein was especially discouraged and hindered by his deteriorating relationship and miscommunications with the Dutch West India Company and the Classis of Amsterdam. According to Capitein’s written job description, he was required to send reports of his ministry to the directors of the Dutch West India Company, which he duly did. However, Capitein had written at least five letters to them, in which he provided feedback on the progress of his ministry and asked advice on numerous questions relating to the ministry, before he received any response. When the Dutch West India Company’s response finally arrived, it was extremely brief and hardly addressed any of his questions. It became evident to Capitein that the Dutch West India Company did not understand his circumstances in Elmina, and their replies were strongly marked by apathy towards his struggles. [27] At the same time, a series of miscommunications with the Classis of Amsterdam was of such discouragement to Capitein, that he even expressed his wish to be relieved of his duties, something which never materialized. [28] These misunderstanding and miscommunication between Capitein, the Classis of Amsterdam, and the Dutch West India Company permanently soured Capitein’s relationship with these authorities. In addition to these troubles, Capitein, despite having the second-highest salary of the Elmina Castle staff, had accumulated great debts which he owed to several people. This was most probably a result of a mismanagement of his finances and reckless spending in trade, which only served to dampen his missionary zeal and general morale. [29] Despite having started his work in Elmina with great zeal and with early signs of promise, the last few years of Capitein’s life were marked by a sense of failure and dejection.

Death

Capitein’s accumulated troubles and frustrations ultimately led to his demise, and he died suddenly of an unknown cause on February 1, 1747, at the age of only thirty. A rumour soon spread after Capitein’s death that he had apostatized from the Christian faith, turned to drinking, and defected to traditional African religion towards the end of his life. [30] This rumour is, however, purely speculative, and cannot be confirmed by any of the available sources. [31] Capitein may have died in a state of dejection, but there is no evidence that he lapsed from his Christian faith.

Jake Griesel

Notes

- The most detailed account of Capitein’s life is David Nii Anum Kpobi, Mission in Chains: The Life, Theology and Ministry of the Ex-Slave Jacobus E.J. Capitein (1717–1747) with a Translation of his Major Publications (Zoetermeer, 1993). Other elaborate studies on Capitein include Albert Eekhof, De Negerpredikant Jacobus Elisa Joannes Capitein 1717–1747 (The Hague, 1917), Grant Parker, The Agony of Asar: A Thesis on Slavery by the Former Slave, Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, 1717–1747. Translated with Commentary (Princeton, 2001), Kwesi Kwaa Prah, Jacobus Eliza Capitein: A Critical Study of an 18th Century African (Braamfontein, 1989), Henri van der Zee, ‘s Heeren Slaaf. Het Dramatische Leven van Jacobus Capitein (Amsterdam, 2000), Jake Griesel, “Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein (c. 1717–1747): The Dissertatio Politico-Theologica de Servitute, Libertati Christianæ Non Contraria in historical-intellectual context” (M.Th Thesis: University of the Free State, 2015), and idem, “Paving the way for Dutch colonial missions: Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein (c. 1717–47) and his defence of slavery in context”, Journal of Early Modern History 26.1–2 (Mar., 2022): 59–78.

- Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, Dissertatio Politico-Theologica de Servitute, Libertati Christianæ Non Contraria (Leiden, 1742), xi; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 51.

- Capitein, Dissertatio, vii–viii; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 58; Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 13; Parker, The Agony of Asar, 10.

- Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, Staatkundig-Godgeleerd Onderzoekschrift over de Slavery, Als Niet Strydig tegen de Christelyke Vryheid, trans. Hieronymus de Wilhem (Leiden, 1742).

- For an elaborate analysis of Capitein’s Dissertatio in its historical-intellectual context, see Griesel, “Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein”. For a condensed but slightly revised version of this study, see idem, “Paving the way for Dutch colonial missions”.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 27; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 70–1; Parker, The Agony of Asar, 11; Prah, Jacobus Eliza Capitein, 42.

- This sermon was published as Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, Het Groote Genadeligt Gods in Zyne Dienaaren onder de Bediening der Genade (Leiden, 1744). Translation of title: “The Great Light of God’s Grace in his Servants under the Ministry of Grace.”

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 39, 44–5; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 135–38, 237–38.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 46; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 138–39.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 238.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 45; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 139, 237.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 139–40; C.R. Boxer, The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600-1800 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965), 230.

- Capitein, Dissertatio, vii.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 235.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 54; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 73, 236.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 56; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 74.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 146.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 48; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 239.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 238–39.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 146–47, 240–41.

- Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, Vertaaling van het Onze Vader, de Twaalf Geloofs-Artykelen, en de Tien Geboden des Heeren, uit die Nederduitsche Taal, in de Negersche Spraak, zo als die Gebruikelyk is van Abrowarie tot Apam (Leiden, 1744). Translation of title: “Translation of the Our Father, the Twelve Articles of Faith, and the Ten Commandments of the Lord, from the Dutch Language into the Negro Speech, as used from Abrowarie to Apam.”

- Capitein, Vertaaling, 6.

- Capitein, Vertaaling, 5–7.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 149.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 151.

- David Kofi Amponsah, “Christian Slavery, Colonialism, and Violence: The Life and Writings of an African Ex-Slave, 1717-1747,” Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 4 (2013): 446; Harvey M. Feinberg, “Africans and Europeans in West Africa: Elminans and Dutchmen on the Gold Coast during the Eighteenth Century,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, no. 7 (1989): 145. For a detailed account of this conflict, see Harvey M. Feinberg, “An Incident in Elmina-Dutch Relations, The Gold Coast (Ghana), 1739-1740,” African Historical Studies 3, no. 2 (1970): 359–72.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 152–54.

- Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 248.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 68–9; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 78, 172; Prah, Jacobus Eliza Capitein, 51.

- Henri Grégoire, De la Littérature des Nègres (Paris, 1808), 223–35; Johannes Menne Postma, The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade 1600-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 71; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 78–9.

- Eekhof, De Negerpredikant, 72; Kpobi, Mission in Chains, 79.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amponsah, David Kofi. “Christian Slavery, Colonialism, and Violence: The Life and Writings of an African Ex-Slave, 1717-1747.” Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 4 (2013): 431–57.

Boxer, C.R. The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600-1800. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965.

Capitein, Jacobus Elisa Johannes. Dissertatio Politico-Theologica de Servitute, Libertati Christianæ Non Contraria. Leiden, 1742.

Capitein, Jacobus Elisa Johannes. Staatkundig-Godgeleerd Onderzoekschrift over de Slavery, Als Niet Strydig tegen de Christelyke Vryheid. Translated by Hieronymus de Wilhem. Leiden, 1742.

Capitein, Jacobus Elisa Johannes. Het Groote Genadeligt Gods in Zyne Dienaaren onder de Bediening der Genade. Leiden, 1744.

Capitein, Jacobus Elisa Johannes. Vertaaling van het Onze Vader, de Twaalf Geloofs-Artykelen, en de Tien Geboden des Heeren, uit die Nederduitsche Taal, in de Negersche Spraak, zo als die Gebruikelyk is van Abrowarie tot Apam. Leiden, 1744.

Eekhof, Albert. De Negerpredikant Jacobus Elisa Joannes Capitein 1717-1747. The Hague: Martin Nijhoff, 1917.

Feinberg, Harvey M. “An Incident in Elmina-Dutch Relations, The Gold Coast (Ghana), 1739-1740.” African Historical Studies 3, no. 2 (1970).

Feinberg, Harvey M. “Africans and Europeans in West Africa: Elminans and Dutchmen on the Gold Coast during the Eighteenth Century.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, no. 7 (1989).

Grégoire, Henri. De la Littérature des Nègres. Paris, 1808).

Griesel, Jake. “Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein (c. 1717–1747): The Dissertatio Politico-Theologica de Servitute, Libertati Christianæ Non Contraria in historical-intellectual context”. M.Th Thesis: University of the Free State, 2015.

Griesel, Jake. “Paving the way for Dutch colonial missions: Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein (c. 1717–47) and his defense of slavery in context”, Journal of Early Modern History 26.1–2 (Mar., 2022): 59–78.

Kpobi, David Nii Anum. Mission in Chains: The Life, Theology and Ministry of the Ex-Slave Jacobus E.J. Capitein (1717-1747) with a Translation of His Major Publications. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum, 1993.

Parker, Grant. The Agony of Asar: A Thesis on Slavery by the Former Slave, Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, 1717-1747. Translated with Commentary. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001.

Postma, Johannes Menne. The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade 1600-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Prah, Kwesi Kwaa. Jacobus Eliza Capitein: A Critical Study of an 18th Century African. Braamfontein: Skotaville Publishers, 1989.

Zee, Henri van der. ‘s Heeren Slaaf. Het Dramatische Leven van Jacobus Capitein. Amsterdam: Balans, 2000 .

This article, received in March 2022, was written by Jake Griesel (PhD, University of Cambridge), a Lecturer in Church History and Anglican Studies at George Whitefield College in Cape Town, and Research Associate in the Faculty of Theology at North-West University, South Africa.

Photo Gallery