Gathuna, George

Early years, education and family life

Bishop George was born Arthur Gatungu Gathuna in the year 1905 in Kenya, in the village of Gathūngu, Ndwaru Road in Riruta, Nairobi West. His parents were Gathuna Muthiora and Wanja Kinuthia, while his siblings were four brothers and one sister. As a young boy and into his teenage years he mainly cared for his father’s flock. He entered Ruthimitu Primary School in 1918 for his lower primary education, before entering middle school at Mambeere in Thogoto, Kikuyu before 1922. He was circumcised later that year with the riika ria ciringi (agemates of the one shilling group). Arthur would then attend Alliance High School from 1928–1930. He did exceptionally well. He was thus sponsored by the Thogoto Scotland Missionaries to join Chogoria Teachers College in Meru for a year. He taught in Chogoria area under the Scotland Missions after his graduation and then at Mang’ara school in Limuru from 1931. He later joined the Ruthimutu Karing’a School as from 1932, a school formed after the breakaway of the Africans from the British missionary churches and schools in 1929.

While at Ruthimutu Karing’a School, Arthur was sent by the Karing’a church to Kandara, Muranga in 1936. His task was to officially translate for Archbishop Daniel William Alexander of South Africa of the African Orthodox Church in South Africa, at the Orthodox Seminary in Gituamba village where the first Kenyan cohort of that school and the Orthodox faith were taught for eighteen months. Arthur would later turn out to not only be a brilliant translator but also an excellent learner to an extent that Archbishop Alexander received him as one of the students. Thus, Arthur graduated on 27th June 1937, with the rest of this first cohort, which he was also translating for. He would later receive an honorary degree to complement all his achievements in the Orthodox faith in December 1985 at Gregory Palamas Monastery in Etna, California USA.

Arthur married Frasier Wambui, the daughter of Karanja Muthoka of Ruthimitu, Dagoretti South, in 1944. Although the custom then was to have many children, the couple had only two children, Stephen Mbugua (1945–2014) and Oliviah Wanja (1948–1964). This could be attributed to the national liberation processes, which Reverend Arthur Gathuna was central in, which forced such leaders to be mainly separated from their families and stay in hiding. Presbytera Frasier Gatungu departed from this life in 1965, and soon after, their daughter Oliviah passed on. Reverend Arthur could not marry again due to the canonical implication of the Greek Orthodox priesthood that once ordained, one cannot contract any lawful marriage. Bishop George’s daughter-in-law, Jane Wanjuhi Mbugua, and her two adopted children Arthur Gatungu and Frasier Wambui, are the only surviving members of this family who live in the bishop’s homestead in Kwa Ng’ang’a, Ndwaru Road in Riruta, Nairobi West.

Politics, priesthood, and ministry

On 1st June 1953, the British colonial government in Kenya arrested Reverend Arthur, together with other Mau Mau liberation fighters, including the famous Kapenguria six arrested on 21st October 1952. Reverend Arthur possibly remains the only Kenyan cleric arrested due to his senior position in the Mau Mau liberation movement. His arrest was because he was the cleric of the liberation church and the head teacher of the school system that produced most of the liberation soldiers and adherents. Reverend Arthur was imprisoned in Senya in Kajiando, then later transferred to Lamu where he stayed until 1958, and finally in Hola where he served his time until his release in 1961, having served a total imprisonment of eight years.

After independence, Fr Arthur was nominated by the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party as a Councilor of the Nairobi City Council government for the years 1963–1970, and later vied for the larger Dagoretti Ward position succeeding Ms Margaret Wambui Kenyatta, who left the position to take over as the City mayor. Reverend Arthur served the Council in different positions including serving as the Nairobi Councilor attending the Kiambu Municipal Council and as a Chairman of different Council committees until his departure from politics in 1979.

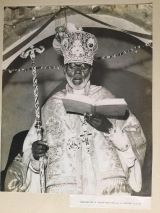

Reverend Arthur was ordained a priest in 1937 in Waithaka, Nairobi County, by Archbishop Daniel William Alexander and started his ministry in his home area in Nairobi-Kiambu Counties as a lone priest of the African Orthodox Church of Kenya. He was elevated to the status of Patriarchal Vicar for the church of Kenya in 1946 by Patriarch Christophoros II Danilidis, after the East African congregations were received under the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa. He was elevated to the rank of Archimandrite during the reign of his former Archbishop, Patriarch Nicholas VI Varelopoulos, and soon after consecrated as the Bishop of Nitria on 25th February 1973 at Saint Paul Kagira, Nairobi West. Metropolitan Frumentios Nassios of Irinoupolis (in office 1973–1982), assisted by two newly consecrated assistant bishops, Christophoros Spartas Sebbanja Mukasa (1899–1982) and Theodoros Nakyama (1924–1997) both from Uganda, led this service. It is during this service that Reverend Arthur was given a new first name of Saint George the Great, to henceforth be Bishop George. As a hierarch, Bishop George became the first in many ways. He was the first Kenyan to become an Orthodox Bishop under the Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa; the first bishop in Africa to be consecrated outside the Patriarchal headquarters in Egypt; the first Assistant Bishop of the church of Kenya; and the first Kenyan widowed priest to become a bishop.

Defrocation and schism

Bishop George’s consecration to the episcopacy had some opposition from four of the younger priests, Peter Michara, Gerasimos Gachumi, Eleftherios Ndwaru and Dimitrios Kinyanjui. According to Rev. John Ngethe, who was Bishop George’s deacon and secretary for long, these priests thought of him as an old man who was too stringent and who abused the young ones excessively. After his consecration, this did not diminish but was rather reinforced. According to Rev. John Ngethe and Rev. Peter Michara, the defrocking was connected to the 1974 national elections in Kenya.

There were two candidates for the local seat of Member of Parliament within Dagoretti, an Orthodox Christian Dr Johnstone Muthiora, a first cousin to Fr Councilor John Ngethe, and a non-Orthodox who was the seating MP, Dr Njoroge Mungai. Dr Njoroge Mungai, a freedom fighter, was highly friendly to the Orthodox, and was a first cousin and personal doctor to President Jomo Kenyatta. Because the Orthodox Christians constituted the majority of voters within the Dagoretti constituency, whoever they accepted was almost an automatic winner. Dr Muthiora was very popular with his fellow Orthodox clergy and laity, and especially Bishop George and thus seemed like an automatic winner. In the process, President Kenyatta intervened and requested his friend, Bishop George, to support his relative Dr Njoroge Mungai, and thus Bishop George started campaigning for Dr Njoroge Mungai, winning to his side only one clergyman Rev. Eleftherios Ndwaru and a few lay people. All other clergy and lay people were strongly behind the former favorite candidate Dr Muthiora. As a leader of all these clergy and lay people, Bishop George was highly embarrassed and took offense. The local councilor Rev. John Ngethe, the then Attorney General Charles Njonjo, and the Vice President Daniel Moi, supported Dr Muthiora vehemently.

This contest was also about who would become the next President of Kenya, after the sickly and aged Mzee Jomo Kenyatta. The sitting MP of Dagoretti, Dr Njoroge Mungai, was pushing to be the next president, while the current Vice President Daniel Moi, with the help of the Attorney General, Charles Njonjo, was seeking the same position. Thus, the attorney general and the vice president funded Dr Muthiora to shake down the popularity of Dr Njoroge Mungai locally, which would make him lose his ministerial position and national popularity. Dr Muthiora won and Bishop George’s candidate thus lost, to his great disappointment. Dr Muthiora died a year after in a very suspect way similar to another MP, JM Kariuki, who had died a week earlier. This did not help matters, for the supporters of Dr Muthiora felt cheated by those of Dr Njoroge Mungai who would later reclaim the seat.

The clergy who supported Dr Muthiora, among them being those who had opposed Bishop George’s consecration, realized they could use this political hostility to overturn things against Bishop George. Our two informants, Reverends Peter Michara and John Ngethe, together with nine others, Dimitrios Kinyanjui, Ioanikios Gachau, Peter Wangige, Eleftherios Wainaina, Chrysostomos Kagwima, Paul Nyore, Paul Kagucia, Ephantus Kamiaraho, and Gerasimos Gachumi, wrote a letter to Patriarch Nicholas VI through Metropolitan Frumentios in 1978. In the letter they highlighted how Bishop George was wrongly consecrated and a terrible bishop who did not obey the local Metropolitan and who did Protestant services within the Orthodox Church. The local Metropolitan, Frumentios Nassios (d. 1982), who had consecrated and let Bishop George operate freely, is said to have tried to stop them, knowing most of these were false accusations, but they could not listen. The clergy rather urged him with other lay leaders and clergymen to take it to the level of defrocking Bishop George.

According to Rev. Michara and Rev. Ngethe, Patriarch Nicholas and Metropolitan Frumentios arranged for a meeting with all these clergy and Bishop George in Nairobi, but Bishop George did not show up, giving the same clergy more time to smear his name. Considering the Patriarchate would not accept the idea of interdependence and autonomy, which Bishop George kept pushing for, and the fact that Bishop George did not fully understand his place as an assistant bishop, for he did a lot of things without consulting the Metropolitan, not forgetting his refusal to meet the Patriarch, Metropolitan Frumentios easily agreed to go with the supposed accusations. The Metropolitan revealed to the involved clergy and laity, as attested by Rev. Michara and Rev. Ngethe, how he would make Bishop George agree to go to Alexandria for the synodal meeting by lying to him that he would be elevated to the status of Metropolitan and henceforth would be independent of any Greek bishop. Bishop George fell for it.

Thus due to these contextual and theological issues that created a rift between Bishop George, the Kenyan clergy and essentially the Alexandrian hierarchy, this Kenyan bishop was defrocked on 30th November 1979. This was after the Holy Synod led by Pope and Patriarch Nicholas VI Varelopoulos together with thirteen Metropolitans sat in Egypt and resolved the same, with only two of the youngest hierarchs, Ireneos of Accra and Petros of Aksum, dissenting. In his response letter on this subject Bishop George took the verdict as a biased preconceived verdict, where he was wrongly accused in Greek, a language he could not understand or respond in, by a synod full of Greek 12 hierarchs who did not understand the contextual mission matters of which he was accused.

According to Rev. Michara and Rev. Ngethe, Bishop George had not done all the things they wrote in the letter, but they had three authentic reasons that pushed them to write against him. First, Bishop George abused them openly in front of the congregants and even their families, which brought much shame to them. Although such language was common among the aged in society like Bishop George, they were not comfortable hearing that within the church context and especially in front of their wives and children. Secondly, Bishop George repeatedly told the lay people that these clergy were too hungry for money, another aspect these clergy were not happy with, seeking to know where this hierarch wanted them to get their salaries from, while they were not as rich as he was. A third reason, which pushed this clergy to the edge, was the common trend of Bishop George working very closely with the elderly lay people to run the church, without much involvement of these clergy. When Bishop George, who was extremely busy, was not available, such a council of elders led the church business without consulting these younger clergy. For them this cultural trend was diminishing their strength as clergy in the parishes.

These clergy, according to Rev. Ngethe and Rev. Michara, would only later realize the implications of falsely accusing Bishop George, and ask for forgiveness from Bishop George who gladly gave it to them in 1985. He asked them to end the existing conflict and protect the AOCK lands and resources from the Greeks, for to him, the battle for autonomy was to never finished until the Kenyans would get it.

Most of the Kenyan faithful could not understand why Bishop George, their founding father and shepherd, was defrocked. They actually considered him a “victim of white colonialists.” As Rev. Michara explains, it was the use of the same words used during the colonial times, Muthungu (white man, here referring to the Greek hierarchs) and Mundu Muiru (black man, here referring to Bishop George), that fueled the schism and subsequent conflicts in Kenya. Considering the Orthodox Christians were in the national Mau Mau liberation movement where the same terms were used, such was the beginning of a battle cry and thus an internal conflict ensued.

After his defrocking, some Kenyans, whom Bishop George had sent to study and were now living in Greece, helped him rebel further and later join one Old Calendar schismatic group from Greece known as the Holy Synod in Resistance. There he was to be given the title of Metropolitan, which he had been falsely promised by Metropolitan Frumentios. In fact, when Bishop George returned to Kenya as promised, he told the Kenyans that he got the title of 13 Metropolitan, although he was still waiting for his application to be reviewed by the Old Calendarists. This new synod elevated him to the rank of Metropolitan on 8th August 1984 at Saint Irene New York, USA, and he has since held the title Archbishop of Kenya, holding this title as the first one in history. In the beginning, only a few priests and parishes who were involved in the defrocking were not with Archbishop George, but after Archbishop Anastasios’s many efforts to reunite the Kenyan church, the Western Kenya clergy, as well as those of Nyeri and Laikipia returned to the Alexandrian side. Although Archbishop George’s side was mainly holding churches within the central region of Kenya, he had the most churches and members, compared to that of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, even with his side being considered officially schismatic and uncanonical.

The original idea of bringing Archbishop Daniel William Alexander to Kenya was to have him ordain a few Kenyans who would then henceforth continue with the local church unaided. Thus, when the Kenyans joined the Greek tradition, the same mentality was always on focus, that one day when some of them became bishops they would be left to run their church, independently from the Greeks. Bishop George, who had not studied much Eastern Orthodox theology, did not understand or probably never cared about the ecclesiology of what a local church meant and what this meant for a diocese and a diocesan bishop. He and Bishop Christophoros Spartas continued with their demand for independence and autonomy, especially after their episcopal elections in 1972 and consecrations in 1973. In fact, it was Bishop Anastasios Yannulatos, who had been sent to East Africa to help heal the schism, and the death of Bishop Christoforos that made the independence agenda not develop much in Uganda.

Assessing this situation as the acting Archbishop of Kenya (1981–1991), Archbishop Anastasios Yannoulatos explains that the fact that Metropolitan Frumentios was too reluctant to serve the Africans had given Bishop George excessive power in leadership. This had led the locals to believe that Bishop George was the hierarch of the blacks and Metropolitans Frumentios of the three hundred whites (200 Greeks from Greece and Cyprus, and 100 Lebanese) in Kenya. This thickened the plot of independency and autonomy, which Bishop George always wanted since the formation of the AOCK.

This was further reinforced by the existence of two church registrations, the African Orthodox Church of Kenya first registered in 1933 and subsequently in 1965 after independence, which was led by Bishop George, and the Holy Archbishopric of Irinoupolis (reg. 1968) led by the sitting Metropolitan. Bishop George used this situation to declare constantly that the AOCK had no relations with the Patriarchate of Alexandria, and that it was always independent since 1933 when it was first registered. Furthermore, the Patriarchate of Alexandria, according to Archbishop Anastasios hastily defrocked Bishop George, without first investigating, what he later came to note as defrocking provoked by some clergy who did not like Bishop George, besides the incompetence of the then Metropolitan Frumentios to understand his own clergy. Archbishop Anastasios tried his best to bring back Bishop George to the jurisdiction of Alexandria, but the fact that he had the title Archbishop, had a large flock that followed him, kept ordaining and celebrating as a hierarch, and his goal of wanting autonomy, made it impossible. On this matter, Archbishop Anastasios gives the best way forward to such challenges, including teaching Orthodox theology seriously in mission lands, producing contextualized constitutions for Orthodox churches in the mission, ordaining local clergy and hierarchs as soon as they are ready, and studying the contexts of the mission. If all these had been done, he believes, there would never have been a schism in Kenya.

Demise and lifting

After having been diagnosed with diabetes for some years, Bishop George became very weak in his old age, but never stopped ministering to his spiritual children. On his deathbed, he forgave and embraced the clergymen who had falsely accused him, as confirmed by Rev. Ngethe and Rev. Michara. He emphasized to all Kenyans that he would always have one eye open, even in his grave, to look and punish whoever tries to destroy the church he so diligently worked for. Bishop George departed from this life on 27th July 1987 at 5:30 pm at the age of 82 years. True to his words, not even the morticians could close his right eye, which was fully open during the burial. Bishop George was buried at the parish of Saints Raphael, Nicholas and Irene in Thogoto-Kiambu, Central Kenya, where he had proposed to be buried before his demise. The service was led by his successor Metropolitan Niphon Kiggundu, assisted by the president of his new synod; the Holy Synod in Resistance, Metropolitan Cyprian Kutsumbas of Oropos & Fili in Greece, who was accompanied by the England-born Archimandrite Fr Ambrosios Adrian Baird (later the Bishop of Methone from 1993). Bishop George’s tomb remains a historic monument for the Orthodox Christians in Kenya, visited by the Orthodox at will, and especially on his annual memorial on 27th July.

Evangelos Thiani

Bibliography

African Orthodox Church Archives Record Group Number 005 from the manuscript collection of Pitts Theology Library of Emory University as processed by Anita K. Delaries. Box 8, Folder 78.

Akunda, Amos Masaba. 2010. Orthodox Christian Dialogue with Banyore Culture. Johannesburg. University of South Africa.

Applegate, Andrew. 2015. “The Orthodox Church process of Canonization/ Glorification and the Life of Blessed Archbishop Arseny.” The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity vol x, No.1. 1‒34.

Chryssavgis, John. 2009. Remembering and Reclaiming Diakonia. The Diaconate Yesterday and Today. Brookline. Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

FitzGerald, Kyriaki. . Women Deacons in the Orthodox Church. Called to Holiness and Ministry. Brookline. Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

Hayes, Stephen. 1996. “Orthodox Mission in Tropical Africa.” Missionalia 24. 383‒398.

———-. 1998. Orthodox Mission Methods. A Comparative Study. Johannesburg. University of South Africa.

———-. 2010. “Orthodox Diaspora and Mission in South Africa.” Studies in World Christianity 16.3. 286‒303.

Kangethe, Kamuyu. 1981. The Role of the Agikuyu Religion and Culture in the Development of the Karing’a Religio-political Movement 1900‒1950 with particular reference to the Agikuyu concept of God and the rite of initiation. Nairobi. University of Nairobi.

Phone or in person interviews with:

- Kamau, Theophanes Patrick

- Mbugua, Jane

- Michara, Peter

- Muchai, Kahuho Peter

- Ngethe, John

- Tillyrides, Makarios

Marina, Abbess. 2004. Mission and Diakonia. Tools of Witness. An Experience from Kenya. Unpublished presentation at the International Conference on the Social Witness and Service of the Orthodox Churches, April 30th – May 5th 2004. Valamo monastery, Finland.

Nganda, Thomas. 2009. “How the Orthodox Church Started in Kenya.” Orthodox Archbishopric of Nairobi. Yearbook and Review. Nairobi. Orthodox Archbishopric of Nairobi/Kenya. 162‒215.

Njoroge, John Ngige. 2011. The Christian Witness and Orthodox Spirituality in Africa. The Dynamism of Orthodox Spirituality as a Missionary “Case” of the Orthodox Witness in Kenya. Thessaloniki. University of Thessaloniki.

——–. 2011. “The Orthodox Church in Kenya and the Quest Enculturation. A Challenging mission Paradigm in Today’s Orthodoxy.” St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 55:4. 405‒ 438

——–. 2013. “Incarnation as a Model of Orthodox Mission. Intercultural Orthodox Mission- Imposing Culture and Inculturation.” Petros Vassiliadis (ed.), Orthodox Perspectives on Mission. Oxford. Regnum Books Internat. 242‒ 252.

Patriarchate of Alexandria. 2009a. “Second Day of the holy synod session of the Patriarchate of Alexandria 7/10/2009 (in Greek).” http://www.patriarchateofalexandria.com/index.php?module=news&action=det ails&id=374 Accessed on 2nd June 2019. ——–. 2009b. “The Patriarchate of Alexandria for Deacons and the Holy Synod (in Greek).” https://www.romfea.gr/epikairotita-xronika/11485-to-patriarxeioalejandreias-gia-diakonisses-kai-agia-sunodo Accessed on 2nd June 2019.

Patrick, Brian. 2017. “A Public Statement on Orthodox Deaconesses. By concerned clergy and laity.” https://orthodoxethos.com/post/a-public-statement-on-orthodoxdeaconesses Accessed on 2nd June 2019.

Rommen, Edward. 2017 Into All the World. An Orthodox Theology of Mission. Yonkers. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Salapatas, Dimitris. 2014. “Sainthood in the Orthodox Church.” Orthodox Herald, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. Issue 304–306. 25–27.

Stamoolis, James J. 1986. Eastern Orthodox Mission Theology Today. Minneapolis. Light and Life Publishing Company.

Thiani, Evangelos. 2016. “A Recipe for Dependency.” Mission Frontiers, Sept/Oct 2016. 33–34.

———. 2018. “The contribution of Daniel William Alexander to the birth and growth of Eastern Orthodoxy in East Africa.” Journal of African Christian Biography 3.1. 29–34.

Vagaggini, Cipriao. 2013 Ordination of Women to the Deaconate in the Eastern Churches. Essays by Cipriano Vagaggini. Ed. Phyllis Zagano. Collegeville. Liturgical Press.

Yannoulatos, Anastasios. 2010. Mission in Christ’s Way. An Orthodox Understanding of Mission. Boston – Geneva. Holy Cross Orthodox Press & World Council of Churches Publications.

——-. 2015. In Africa. Orthodox Christian Witness and Service. Boston. Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

The Very. Rev. Protopresbyter Fr. Evangelos Thiani is a member of the Editorial Board of the DACB and a JACB Contributing Editor. This biography is an excerpt from his article “Call for Ecclesial Recognition of Bishop George Arthur Gatungu Gathuna (1905-1987), The Founding Father of the African Orthodox Church of Kenya,” In Journal of African Christian Biography 6, no. 1 (Jan 2021): 2-27.