Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Rainisoalambo (A)

The revival movement that was spreading throughout Europe in the 19th Century also made its’ way to the Isandra region and the Betsileo area of Madagascar, where a man named Rainisoalambo lived.

The revival movement that was spreading throughout Europe in the 19th Century also made its’ way to the Isandra region and the Betsileo area of Madagascar, where a man named Rainisoalambo lived.

Rainisoalambo lived alongside all of the Betsileo princes in Ambalavato, a rural village, connected to Ambatoreny quarter, east of the Soatanàna district in Fianarantsoa. He was descended from a line of diviners who were responsible for educating the princes, and he was raised in their midst.

Rainisoalambo was chief of the royal guard and also served as the public voice of the sovereign because of his great gift for witty banter and public speaking. He was also in demand as a sort of lawyer, as he was skilled in persuasive argument. Because he almost always won whatever case he argued, people who needed someone to speak for them frequently hired him.

He was also renowned as a traditional healer and diviner.

Around 1892, as he was getting on in years - he was about sixty - he left his work at the court and devoted himself to agriculture (rice, in particular) in the hope that he could earn more money that way.

The London Mission Society (LMS) [1] had already started a church in the village of Ambatoreny that also served as a school. When not in use for services, the pastor used the building for school, and also served as the teacher. Pastor-evangelists like him were trained in the theological institutions of the LMS. They were very disciplined, wore European-style clothing, were paid, and were not subject to forced manual labor. In fact, to the local residents, they represented a new way of living.

Rainisoalambo coveted their way of life and thought that he could become like them if he too became a pastor. He was an ambitious and intelligent man, and with the encouragement of his friends, he learned to write and to read the Bible. He was baptized in 1884, and hoped that he would become wealthy when he was ordained as a pastor. In the meantime, he didn’t abandon his pagan practices. After a six month course of Bible instruction, he was appointed as a non-salaried catechist to the parish. Disappointed, he went back to his former work as a farmer and healer/diviner.

At that time, the standard of living was very low for people in remote villages like the one in which Rainisoalambo lived. There was a famine at that time, and an epidemic of smallpox and malaria also swept through the region, killing many people. In addition to those tragedies, the Bara and the Sakalava [2] - two tribes living in the vicinity of the Betsileo tribe – took turns attacking and plundering the surrounding villages. People were also burdened by taxation. The king required that all males past their childhood years pay taxes that helped to pay the fines imposed by the French colonizers. Charms and pharmacopoeia couldn’t heal poverty, malnutrition and sickness.

Rainisoalambo’s family was decimated until he had only seven heads of cattle left. His rice paddies lay fallow and uncultivated. He grew very sick and lived on next to nothing, as his body was covered with painful sores that made it impossible for him to work. All his friends left him.

From the depths of his misery and despair, Rainisoalambo called on the God that he already knew about. That very night, October 14, 1894, according to his testimony, he had a dream while he was asleep. In the dream, he saw someone dressed in a white garment that was indescribably white standing next to him, telling him to throw out his amulets and abandon the things he used for divination, as they had served both to protect him and to give him his identity as a diviner.

The next day, at dawn, he carried out the order and threw away his baskets full of pieces of wood, of grain and of pearls. Right away, he felt delivered of his pain, and his strength came back. He felt like a new man. All of this happened on October 15, 1894. In his words, a certain Jesus had delivered him from the depths of the pit and had freed him of his pagan chains. He repented, and immediately felt like he had been freed. He washed his body, then cleaned his house and his courtyard.

Since he already knew how to read, he began to carefully read the Bible, especially the New Testament. He already knew certain things about prayer and the rites of the Christian church and community, but it was after he had spent many weeks studying and meditating on the Bible that he began to spread his message.

He first spoke to his family, as several of them were ill and were practicing the ancestral religion. The central theme of his preaching was that one needed to move away from idolatry and cling to Jesus Christ, the One who had appeared to him and had spoken to him. He told them that if they wanted to be healed, they should throw out their fetishes. Many of them followed his advice and were healed. He then went to the neighboring villages, visiting and praying for those who were so sick that they couldn’t even pray. He laid hands on the sick, proclaiming that Jesus was the source of all healing, and they were healed. All of this took place between the end of 1894 and the first half of 1895.

On June 9, 1895, Rainisoalambo gathered the twelve people [3] who had first been healed after having thrown away their idols and laying aside their pagan life. They prayed together, and took the following solemn commitments: to learn to read and to learn how to count, so that they could read the Bible by chapter and verse; to clean their houses and courtyards, and to have a separate cooking area so that homes would be clean enough to meet in and so that God would be honored [4]; to have their own vegetable gardens and sources of food; and to start everything with prayer in the name of Jesus. They also decided that burials, which could ruin a family and which were often an excuse for pagan drunkenness and debauchery, would take place in nice clothes, and that there would be songs, prayers and exhortations, but no slaughtering of cattle. This was also done to protect the grieving family, so that they wouldn’t have to impoverish themselves on such occasions. Rainisoalambo ended the meeting with Bible reading and prayer. That small but extraordinary meeting gave birth to the Mpianatry ny Tompo (Disciples of the Lord).

Rainisoalambo started to teach the members of the group. As they learned, the members continued to work as farmers. Rainisoalambo taught with the help of brochures, including the “Short Catechism” of Martin Luther translated by M. Burgen, which he obtained from Théodor Olsen, a missionary from the Soatanàna (“beautiful village”) Mission Station [5]. He also requested the teaching help of the pastor in Ambatoreny, who accepted and came to teach them every Monday and Thursday.

They organized themselves so that they could lead a life in community. They cultivated the fields and built houses to receive the sick. They preached the Gospel, healed the sick, and delivered the demoniacs who came to see them. In order to always have the Bible with them, they created white cotton bags that they carried slung over their shoulders.

They agreed together to live by the following principles: repentance, humility, patience, love of one another, prayer, communion, and mutual aid. In the early days, Rainisoalambo sent them out on short trips to evangelize nearby, but little by little, they traveled farther and farther away on longer trips. His wish to have a missionary life was granted, but not as he had expected.

Near the end of October, in 1895, having become acquainted with the community and their work of evangelization, the missionary Théodor Olsen wrote: “Something that was cause for rejoicing happened in the village to the west of the station, because about twenty honorable pagans asked if they could be baptized. They had been coming to the Sunday worship service in the parish, and we could also see them studying the Bible and helping each other with readings and Bible studies during the week. One Monday when I went to visit them and to teach, there were about thirty or forty of them, all paying close attention to the sermon I was preaching about the love of God that He extends to sinners.” [translation by the author].

Rainisoalambo’s village, Ambatoreny, quickly became a magnet for many sick people. New converts exhorted them, prayed for them in a loud voice and laid hands on them. Also, many of the “disciples” quickly went to their neighbors and families to tell them what had happened to them and to encourage them to do the same.

In 1902, due to the politics of the colonial situation, the “revival center” was moved to Soatanàna, where it still is today, so that it could be under the aegis of the Norwegian mission there and integrated within the local Lutheran parish.

At the revival center in Soatanàna today, certain Biblical rituals are practiced, such as footwashing. All those who live there are dressed in white - the symbol of purity - and all the Soatanàna zanaky ny Fihohazana (children of revival) rigorously follow the same life principles. Men wear straw hats with a white ribbon. It is also the custom that guests have their feet washed by a resident when they arrive at the center.

Organized along patriarchal lines, and submitted to rigorous discipline, the disciples [of the movement] profess the gift of healing by the laying on of hands. Starting from Soatanàna, the movement spread through its’ Iraka, (“apostles” or “sent ones”) who went from village to village and from town to town on foot, preaching the Good News to all. In 1904, they numbered about fifty, and the number of converts kept on growing.

From the very beginning, Rainisoalambo was at the head of the revival movement. Often worried about the future of the movement because of the ever-present winds of discord, he would frequently go to pray alone near the mountain that is to the west of Soatanàna. He decided to organize a general assembly of the movement’s delegations, which were spread throughout the island, and set the date of August 10, 1904. It would be a great prayer meeting, and would also serve to set up the organization of the movement. Intensive preparations began in Soatanàna for the construction of a large structure that would serve to welcome all the guests. The residents organized the rice planting as well, so that there would be enough rice to feed everyone.

Rainisoalambo managed to direct the preparations for some time, but was eventually tired by the work, given his age. His lungs became afflicted with an illness that got increasingly worse. On the eve of his death, he asked once more to be brought to the construction site. He had to be held up on both sides, as he could no longer walk alone. The following day, some of his friends and his family came to be with him, and stayed around him singing and praying for him. On June 30, 1904, he breathed his last, praying for the movement in Soatanàna.

He was buried in Soatanàna even though his native village was not far away, so as to keep the rule of the movement, according to which one should be buried where one died. [6] The great assembly of August 10 took place without him.

Such is the story of the origins of the first revival movement in Madagascar, which made Soatanàna the first revival center in the land. Soatanàna has now become a great center of yearly pilgrimage, and people go there to be healed and to pray.

The revival movement shook up the social and economic life of the village and of the region. The number of illiterate people declined and respect for personal hygiene made for generally better health conditions for all. The change in customs and behavior at burial ceremonies was an improvement for families. Soatanàna became a model village for the surrounding region.

Berthe Raminosoa Rosoanalimanga

Notes:

-

The LMS (London Missionary Society) arrived in the Betsileo region in 1870 through the person of Rev. Richardson, who lived in Fianarantsoa.

-

There are eighteen different tribes in Madagascar, each with their own customs and dialect, but they can understand and talk to each other in the official language of Madagascar.

-

The first twelve disciples (apostles)–all men–of this revival movement were Rajeremia, Rainitiaray, Razanabelo, Rasoarimanga, Ratahina, Reniestera, Ralohotsy, Rasamy, Ramanjatoela, Razanamanga, Rasoambola.

-

In Soatanàna, up until the time of the revival, and especially in the villages, houses were built with rooms open to the kitchen, so as to conserve warmth in the winter. Since people cooked on a wood fire, the ceilings were often black with soot. Chickens had also been kept inside, but were now put outside so that houses could be kept clean.

-

Soatanàna is a Norwegian mission station that was established by a missionary named Lindo in 1877. Missionary Théodor Olsen took his place in 1891, and was a witness to the birth of the revival movement (1895).

-

According to Malagasy custom, the dead were supposed to be buried in the family tomb. If someone died far from their natal village, one year after the burial, if possible, the family brought the body home to be buried there.

Bibliography

James Rabehatonina, Tantaran’ny Fifohazana eto Madagasikara (1894-1990) [History of the Revival Movements in Madagascar] (Imarivolanitra: Trano Printy FJKM, 1991)

Félicité Rafarasoa, “Fifohazana, the Revival Movement, “ thesis paper , SETELA, Lay Training Center, class of 2001-2002.

Académie Malgache, Bulletin de l’Académie Malgache, [Bulletin of the Malagasy Academy] 1974.

Lucile Jacquier DuBourdieu, “The Role of Norwegian Pietism in the Establishment of Native Christianity in a Rural Betsilao Milieu at the End of the Nineteenth Century: the Case of the Rainisoalambo Revival” in Cahiers des Sciences Humaines, Office de la recherche scientifique et technique outre-mer (Bondy, France), 1996.

A. Thunem, Ny Fifohazana eto madagasikara [The Revival Movement in Madagascar] (Antananarivo: Imprimerie de la Mission norvégienne, 1934).

B. Hübsch, dir., Madagascar et le Christianisme [Madagascar and Christianity] (Paris : Karthala, 1993). Adolphe Rahamefy, Sectes et crises religieux à Madagascar [Cults and Religious Crises in Madagascar] (Paris : Karthala, 2007).

This article, which was received in 2008, was written and researched by Ms. Berthe Raminosoa Rasoanalimanga, director of the FJKM National Center for Archives (1984-2007), and a recipient of the Project Luke Scholarship for 2008-2009.

Photo Gallery

[1] Three leaders of the revival in Soatanàna. From left to right : Rajeremia and his wife, Rainitiaray and his wife, Rainisoalambo and his wife. The Bible is on the table between them. They are wearing a lamba (a type of shawl).

[2] The Mission in Soatanàna, 1892-1895. Photograph: Théodor Olsen.

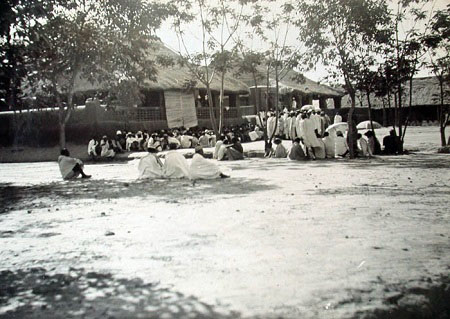

[3] Outdoor meeting in Soatanàna, around 1906.

[4] Group of people outside in the courtyard for a meeting. Betsileo.

[5] Preparations being made for a revival meeting, around 1906. Preparations often took all day.

[6] Revival meeting in Soatanàna, about 1906. Some are seated under parasols.

[7] Landscape around Soatanàna.

All photographs are printed with the permission of the Mission Archives, School for Mission and Theology, Stavanger, Norway.