Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Wilberforce, Daniel Flickinger

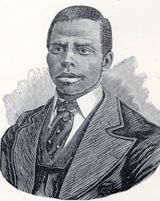

Daniel Flickinger Wilberforce (1856-1927), paramount chief of Imperi, was the first Christian pastor to become a chief. He was educated mainly in the United States of America, returning to Sierra Leone to a post at Clark Theological School in Shenge, north of the Sherbro estuary. He wielded a powerful influence throughout Imperi, but was eventually found to have taken an unsavory part in the political troubles of that area.

He was born at Good Hope in the Jong estuary, Imperreh country, in 1856, and was named after a missionary, the Rev. Daniel K. Flickinger of the Mende Mission in the Sherbro. Wilberforce proved capable and trustworthy. When a lady missionary took seriously ill and had to be repatriated to the United States in 1871, Daniel was chosen to accompany her. On his arrival, he worked in the warehouse of the American Missionary Association. His namesake, Rev. D. K. Flickinger, then secretary of the Mission met Daniel by chance in New York, and immediately took him to Dayton, Ohio, to have him properly educated.

After graduating with honors, Daniel married Elizabeth Harris in 1878. In the same year he was appointed to serve on the staff of the Clark Theological School in Shenge, eventually becoming principal in 1887. Wilberforce obtained a 100-acre tract of land from his family near Gbambaia, south of the Bagru River, where he opened a school in 1882, while he supervised from Shenge. He had plans for a “village of Dan,” which never effectively materialized, but the mission establishment there, including his house, came to be known as “Danville.” This project was sponsored by the King Street United Brethren Church in Pennsylvania. As its evangelical and educational work grew and flourished Wilberforce moved from Shenge to take over personal control of the Danville mission in 1892.

In 1890, Wilberforce found one of his servants murdered at Gbambaia. There were other similar “leopard murders” in the vicinity (ritual murders which nevertheless carried political undertones), misleadingly attributed to “cannibalism.” Wilberforce suggested to the chief that the Tongo Players or traditional witch-detectors, be brought in. A holocaust followed in which over 30 people were burned to death, including Chief Gbanna Bunjay himself.

When the 1898 resistance broke out in opposition to the house tax, imposed by the Protectorate Ordinance, Imperi became the scene of terrible massacres accompanied by the destruction of mission, official, and trading stations. Many missionaries and officials were murdered in cold blood. Wilberforce himself barely escaped with his life after losing much of his property, and his mother and sister were hacked to death while trying to make for Bonthe.

When the hostilities were over, the chief of Imperi and several others were arrested. Wilberforce was appointed paramount chief, after he had assisted the British in quelling the revolt. Through his missionary and educational activities he wielded enormous influence throughout Imperi, and as an educated man in good favor with the colonial authorities, he was well placed to be the intermediary between his people and the administration at this critical period. “There seems to be no alternative,” he wrote.

The administration, however, was rudely shaken in its “civilizing” complacency when a whole series of “leopard murders” were revealed in 1905. To everyone’s amazement, Wilberforce was one of the accused. There was not sufficient evidence to warrant a conviction but, having failed to live up to expectations as a “civilizing force,” he lost his chieftaincy by administrative order. The fact that he was a naturalized American was now invoked; as a foreign national he could not be paramount chief in a British Protectorate.

When another outburst of leopard activity occurred in 1912, Wilberforce was again arrested. A special commission court was constituted to try the accused persons. Once again, for lack of sufficient evidence, he could not be convicted, but the special commission court had power to recommend the banishment of anyone whose presence was felt to be prejudicial to peace and good order. Wilberforce was thus banished to Liberia. He was later pardoned and he returned to his home and continued missionary work there. His last memorable activity was the closing address which he gave to the 1924 annual conference of the United Brethren in Christ mission. He died three years later in 1927 and was buried in the Danville church cemetery near Gbambaia.

Arthur Abraham

Bibliography

Arthur Abraham, Mende Government and Politics Under Colonial Rule, Freetown, 1978; Christopher Fyfe, A History of Sierra Leone, London, 1962; G. D. Fleming, Trail Blazers in Sierra Leone, Vol. I, Indiana, 1971.

Photo source: Flickinger, Rev. D. K. Ethiopia: Twenty Years of Missionary Life in Western Africa. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House, 1877.

This article was reprinted from The Encyclopaedia Africana Dictionary of African Biography (In 20 Volumes). Volume Two: Sierra Leone-Zaire, Ed. L. H. Ofosu-Appiah. New York: Reference Publications Inc., 1979. All rights reserved.