Mursal, Cabdulqaadir

Cabdulqaadir Mursal was born in Harar, Ethiopia at a time of conflict. His father had initially been in the Italian Army during the conquest of Ethiopia in 1935. After the defeat of the Italian forces in 1941, his unit had been absorbed into the British Army. Shortly thereafter, Cabdulqaadir’s father got involved in a dispute with a British officer. He left the unit and joined a group of freedom fighters in the bush. While Cabdulqaadir was still a small child, his father was killed in fighting with Ethiopian soldiers. After that, Cabdulqaadir and his mother lived with his nomadic relatives and sometimes with family members in nearby towns.

Cabdulqaadir Mursal was born in Harar, Ethiopia at a time of conflict. His father had initially been in the Italian Army during the conquest of Ethiopia in 1935. After the defeat of the Italian forces in 1941, his unit had been absorbed into the British Army. Shortly thereafter, Cabdulqaadir’s father got involved in a dispute with a British officer. He left the unit and joined a group of freedom fighters in the bush. While Cabdulqaadir was still a small child, his father was killed in fighting with Ethiopian soldiers. After that, Cabdulqaadir and his mother lived with his nomadic relatives and sometimes with family members in nearby towns.

Following Somali Independence in 1960, Cabdulqaadir decided to leave Ethiopia and move to Muqdisho. When he crossed the border at Beledweyne, the government official asked him to which clan he belonged. However, Cabdulqaadir had been influenced by the teachings of the Somali Youth League and refused to divulge that information. “I am a Somali” was all that he would say.

Shortly after coming to Muqdisho, Cabdulqaadir enrolled in English classes at the SIM night school. After some time, he began to study the Bible, heard the Gospel message and trusted in Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior. Cabdulqaadir became part of the Somali Believers Fellowship.[1] During this time, he moved with his family to Balcad and became an office worker at the SomalTex textile factory.[2]

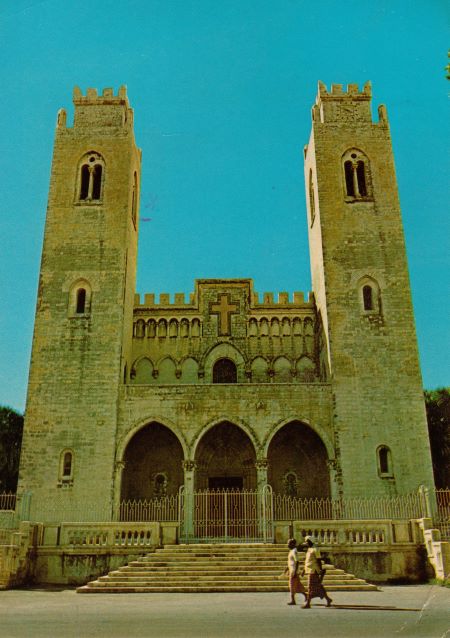

Cabdulqaadir resumed his worship with the Somali Believers Fellowship in 1983, travelling on Fridays to participate in worship services at the Croce del Sud cathedral[3] in Muqdisho. This small group of Somali Christian men and women were given permission by Bishop Salvatore Colombo[4] to use the cathedral for worship each Friday morning. This cooperation shows how the Roman Catholic Church provided assistance to Protestant Christians.

Those who worshipped together there remember how Cabdulqaadir regularly gave testimony as how the Lord was working in his life, and he praised God for His blessings. In one testimony, Cabdulqaadir told what happened when a few Western Christians living in Muqdisho had come to visit him. After they left his home, he was summoned to the office of the National Security Service[5] [secret police] in Balcad for questioning. “Who were those foreigners and why were they visiting you?”

Cabdulqaadir responded in classic Somali style[6], using poetry in his reply to the officer. He told him he had the right to welcome friends and guests to his house. This testimony caused different emotions when Cabdulqaadir shared in that church meeting. It encouraged many but also made others nervous. In those days, it was not common to tell such stories about the secret police in a public meeting.

A member of the Somali Believer’s Fellowship remembered another example of Cabdulqaadir’s poetical gifting. “I also recall him composing a poem on the spot in response to a sermon and reciting it right after the sermon.” Another time, Cabdulqaadir shared about an unusual request he received from a committee of fellow workers at SomalTex. They had collected money to buy several goats for the Eid al-Adha[7] celebration and wanted him to hold onto their money for safekeeping. “You know that I am a Christian,” he told them. “I won’t be celebrating Eid with the rest of you. So why should I keep the money that you are collecting?” His colleagues told him that they respected him for his honesty and thus they needed his help. “We don’t trust each other with this money”.

Yet another time, Cabdulqaadir mentioned being in an accident on a bus near Balcad. As it was rolling off the road, he heard most passengers calling on the names of various Sufi saints for protection. “As for myself, I called out to Jesus Christ to protect me. And he did, I escaped with only minor injuries.”

In 1984, Cabdulqaadir made a remarkable welcome to some refugees from Ethiopia. A small delegation was sent by the Sidama church in the Qoryooley Refugee Camp. This group of about 100 men used a circular hut in the camp for worship. They were strong in faith and growing in numbers within the Sidama part of the refugee camp. However, when a rainstorm damaged their hut that they used for worship, they sent several of their leaders to Muqdisho to meet the Somali Believers Fellowship and request some assistance. After they were introduced, Cabdulqaadir stood up. “My father was killed by Ethiopian soldiers. And many in my country say that we should hate the “Habasha”. But that is nothing for me, you are my brothers in Christ regardless of your nationality, and I welcome you here”.

A friend of Cabdulqaadir recalled this part of his character: “He was indeed a person who took his faith in God seriously and was willing to change his lifestyle when he learned something new.”

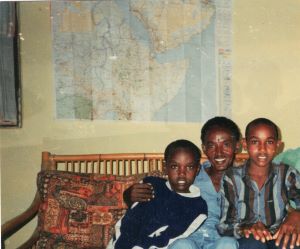

For example, in May 1984, Cabdulqaadir heard a sermon on Deuteronomy 11[8], particularly verse 19 “You shall teach them to your children, talking of them when you are sitting in your house, and when you are walking by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise.” When the sermon was over, Cabdulqaadir stood up and said, “I have done wrong. I only come by myself. From now on, I will try to bring my children.” From that time, he usually was accompanied by his sons to the Friday worship meetings of the SBF. In those days, it was very rare to see any children at these meetings.

In 1985, Cabdulqaadir embarked on a new way of serving his Lord Jesus Christ. At a service in June of that year, he stood up in the testimony time. He said that dreams can sometimes be visions from God. However, most dreams are about people or situations that the dreamer loves or desires. He said, “I’ve written a song about a dream in that second case. I love Jesus Christ, and here is a song I have composed about a dream I had of him.” Cabdulqaadir sang the song Xalay baan Masiixii arkoo, xamdi baygu waajibaye (Last night I saw the Messiah, I must give him praise) to the church. People realized that the words were all based on truths from the Gospel message in the Bible, while the tune was a traditional Sufi dhikr[9]. The church members were very excited, as new Somali Christian music had not been composed for over 10 years.

Over the next four years, Cabdulqaadir composed seven more hymns and presented them to the church for their use in the worship meetings:

- Badbaadshow Masiixow (Oh Savior Messiah!)

- Qalbigayga kuu doortay (My heart chose you)

- Bashiirow Masiixii (Oh Messiah, messenger of the Good News)

- Gacmahaa loo hoorsan (We lift our hands)

- Masiixeennii weynaa (Our great Messiah)

- Nimcaaloow! Masiixii nuurka badnaayoow! (Oh gracious One, the Messiah who is full of light!)

- Maryamoo bikraa baa Masiixii dhashoo (Oh virgin Mary who gave birth to the Messiah)

Cabdulqaadir Mursal died of cancer in 1990 in Balcad, just as the frontlines of the civil war were coming close. Because his clan came from a distant area, he would likely have had to have fled from his home in those days, so this was a mercy from God.

Wherever Somali Christians live and worship today, they remain blessed by the example of the bold faith of Cabdulqaadir Mursal and the eight beautiful hymns he wrote praising the Lord Jesus Christ using the traditional Somali poetic style[11].

Ben I. Aram

Note: The Somali translation of this biography can be found at: https://noloshacusub.com/qoraallo/taariikhda-kaniisadda-soomaalida/qiso-nololeedkii-soomaali-masiixiyiin-ah/cabdulqaadir-mursal

If you would like to hear Cabdulqaadir Mursal in 1988, along with members of the Somali Believers Fellowship of Muqdisho, singing the songs he wrote, then click here.

Click here to listen to Cabdulqaadir Mursal’s songs with traditional instruments.

Click here to listen to Cabdulqaadir Mursal’s songs with modern instruments:

Sources withheld for security reasons.

Notes

- Xayle, Axmed Cali. “Jidkii Nabaddoonka: Qiso-Nololeedkaygii anigoo Ergay Nabadeed ka ah Adduunka Islaamka Dhexdiisa.” Nolosha Cusub, available at https://noloshacusub.com/qoraallo/taariikhda-kaniisadda-soomaalida/jidkii-nabaddoonka, (Accessed July 27, 2023).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Balad District, Somalia,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Balad_District,_Somalia&oldid=1157154167 (accessed July 27, 2023)

- ——-, “Mogadishu Cathedral,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mogadishu_Cathedral&oldid=1119952870 (accessed July 27, 2023)

- ——-, “Salvatore Colombo,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Salvatore_Colombo&oldid=1105788106 (accessed July 27, 2023).

- ——-, “National Security Service (Somalia),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=National_Security_Service_(Somalia)&oldid=1111561565 (accessed July 27, 2023).

- Samatar, Said S. 1982. Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism : the Case of Sayyid Maḥammad ʻAbdille Ḥasan. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Eid al-Adha,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eid_al-Adha&oldid=1165585332 (accessed July 27, 2023).

- Deuteronomy 11:19, from the Somali translation “Sharciga Kunoqoshadiisa,” Nolosha Cusub: Cutubka 11:19, https://noloshacusub.com/kitaabka-quduuska-ah/axdigii-hore/tawreedda/sharciga-kunoqoshadiisa, (Accessed July 27, 2023).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Dhikr,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Dhikr&oldid=1160628770 (accessed July 27, 2023).

This article, received in 2022, was written by Ben I. Aram, who is Director of The New Life Media, a multi-platform social media/website ministry that communicates the Gospel in the Somali language. Ben I. Aram served seven years inside Somalia, then worked in media with Somali refugee Christians in Kenya and Ethiopia for fifteen years.

Photo Gallery