Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Luthuli, Albert John Mvumbi (B)

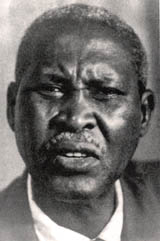

Albert John Mvumbi Lutuli (circa 1898 to July 21, 1967) was the president-general of the African National Congress (ANC) of South Africa for 15 crucial years when black resistance was being mobilized against the republic’s apartheid system. A devout Christian and nationalist, he remained staunchly committed to the end of his life to the Gandhian idea of positive non-violence despite the growing loss of faith in this method of political struggle when prominent figures like his own deputy, Nelson Mandela, embraced the need for an armed struggle. He was the first African ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace.

Lutuli (whose name is usually rendered as Luthuli) came into a chiefly Zulu family and himself became the chief of the Umvoti Mission Reserve at Groutville in Natal, his family’s traditional home. But he was born in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) where his mother, Mtonya, had come to join her husband, John, who was working at the time as an evangelist and interpreter at a Seventh Day Adventist Mission near Bulawayo. His father died while Albert was still in his infancy, and he returned home with his mother when he was about ten years old.

After completing his secondary education in a Christian mission school, he qualified as a primary school teacher at Edendale near Pietermaritzburg in Natal, South Africa. He then taught for a time in a primary school until he was awarded a bursary to qualify as a high school teacher at Adams College in Natal. He later joined the college teaching staff until 1935, when he accepted a call to assume the chieftaincy of his community. By then he had become firmly attached to his Christian religion and had become a lay preacher in the Methodist Church. In 1938 he traveled to India as a delegate to an international missionary conference, and in 1948 he visited the United States for nine months on a church-sponsored tour.

He showed little interest in political affairs outside of his traditional functions as a chief until 1946 when he successfully contested the vacancy to the Native Representative Council caused by the death of his friend and mentor, John L. Dube, a doyen of the ANC. Five years later he began to assume a prominent role in ANC politics when he defeated the redoubtable politician, A.W.G. Champion, to become Natal’s provincial president. In 1952 he supported the Defiance Campaign which resulted in his being dismissed from his position as chief by a government edict. The controversy that followed his dismissal brought him into national prominence. He expressed his own defiance through a personal testament of faith, The Road to Freedom is via the Cross, which has become a seminal document in black nationalist literature. Written with eloquence and passion, Lutuli appealed to all South Africans, white and black, to repudiate apartheid as demeaning to the whole nation. He proclaimed his belief in nonviolence and invited his fellow countrymen to join in the struggle for a shared society which he argued was the Christian answer to the country’s disastrous racial conflicts.

By 1952 Lutuli was widely acknowledged as the most important black voice in the country, a position confirmed when he was overwhelmingly elected in December of that year as the new president-general of the ANC in succession to Dr. James Moroka. But within a few months he was placed under a government banning order restricting him to his own home area. Although this severely curtailed his political activities, Groutville became a center for visitors from all over the country and from abroad. Thus the Zulu sage of Groutville remained in the political limelight, helped by his frequent published statements and interviews. He was twice re-elected as ANC president-general, in 1955 and 1958.

Despite his physical confinement, he was arrested in December 1956 on charges of treason. The charges were dropped a year later, and he was allowed a period of relative freedom until May 1959 when a new political ban was imposed on him. In this brief intervening period, however, he was in great demand as a public speaker, receiving many invitations to address white audiences which drew large crowds. At one such meeting in Pretoria he was assaulted by Afrikaner students, but this only served to enhance Lutuli’s stature. Always tolerant, gentle, and moderate in manner and speech, he pricked the white conscience and inspired black South Africans who increasingly came to look on this dignified old chief as a savior of his people and, possibly, of the country.

In the immediate aftermath of the Sharpeville shootings in 1960, he supported the ANC’s call for a day of mourning and defiantly burned his own pass in a public protest against the indignity of Africans having to carry on their persons, at all times, a document showing that they had paid their taxes and were entitled to live at any particular place in the country. He was promptly arrested and kept in detention for five months, until August, when he was sentenced to pay a fine and given a suspended prison sentence. His ban was reimposed.

In December 1961, however, the government allowed him to travel to Oslo to receive his Nobel Prize for Peace rather than to face the international outcry which had been threatened if permission were refused. Lutuli concluded his memorable award speech with this simple message: “Africa’s fight has never been, and is not now, a fight for the conquest of land, for accumulation of wealth or domination of peoples, but for the recognition and preservation of the rights of man and the establishment of a truly free world for a free people.”

In 1962 he published his autobiography, entitled Let My People Go, which, like his Peace Prize statement, was a call for freedom in South Africa.

But there was still no freedom for this patient, loving and rather old - fashioned crusader; after his triumph at Oslo he returned home to begin a new period of confinement at Groutville. Old and almost blind, he was struck down and killed by a train while walking near his home at Stanger, on July 21, 1967.

Colin Legum

Bibliography:

Mary Benson, The African Patriots: The Story of the African National Congress of South Africa. London: Faber & Faber, 1963.

Gail M. Gerhart, Black Power in South Africa, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978.

Karis, Carter and Gerhart, From Protest to Challenge (four volumes), Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1971-77.

Albert Luthuli, Let My People Go, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962.

This article was reprinted from The Encyclopaedia Africana Dictionary of African Biography (In 20 Volumes). Volume Three: South Africa- Botswana-Lesotho-eswatini. Ed. Keith Irvine. Algonac, Michigan: Reference Publications Inc., 1995. All rights reserved.