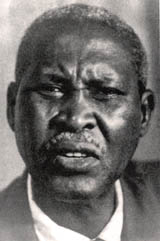

Luthuli, Albert John Mvumbi (D)

“Although he was silenced, history will make his voice speak again, that powerful brave voice that spoke for those who could not speak.”[1]

His Early Life

Albert Luthuli was from Groutville, a missionary reserve, in Natal. In Groutville, there was a close relationship between the people and the missionaries. Although conversion to the Christian religion brought revolution in people’s lives, they remained Africans. According to Luthuli, “They were still Zulus to the backbone—that remained unchanged except for a few irrelevant externals. But they were Christian Zulus, not heathen Zulus, and conversion affected their lives to the core.”[2]

At some point, Albert’s father John Luthuli went to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to serve with the Rhodesian forces. His mother Mtonya followed and soon Luthuli was born in Rhodesia, possibly around 1898, but not later than 1900. As his father died a few months later, the burden for his whole upbringing fell upon his single mother who came from the Qwabe stock, a clan known for its strict discipline.[3]

In 1908/1909, Luthuli’s family left Rhodesia because his brother had responded to the call to begin missionary activities for the Seventh Day Adventists in Natal. Due to a lack of schooling facilities at the new place, his mother sent him back to Groutville to stay with his uncle Martin who was a chief at that time. Although as a child he could not be involved in chieftaincy activities, young Albert was able to witness some of the incidents that were brought to his uncle.[4] Luthuli’s new home impacted his Christian faith. In retrospect, he could later remark: “All the time, unconsciously, I was busy absorbing the Christian ethos of home, and church congregation, and the social ethos of the community.”[5]

His brother and mother came back to Groutville and Luthuli joined them, moving from the Adventist to the Congregational church. The latter tradition would later have an impact on his political convictions and life.[6] His activist stance already manifested during his secondary school years when he became involved in strikes.[7]

In Edendale, where he enrolled for a two years’ teachers’ course, Luthuli was exposed to a context that emphasized personal responsibility and active adult leadership. These qualities left a mark on him. Given the commitment of his school teachers, Luthuli came to love teaching, appreciating his European mentors while at the same time confirming his Africanness: “I am aware of a profound gratitude for what I have learned. I remain an African. I think as an African, I speak as an African, I act as an African, and, as an African, I worship the God whose children we all are. I do not see why it should be otherwise.”[8]

Luthuli married in 1927 and the family was blessed with seven children. Due to the very hard conditions in South Africa then, the parents prayed for their children. Luthuli appreciated the role that his wife played in his life and family. As could be expected, when Luthuli became a public figure of considerable magnitude, his wife had to run the family single-handedly many a time.

His Work as a Teacher

When he finished his teacher training, Luthuli went to Blaauwbosch in the Natal uplands to teach.[9] In the absence of a Congregational church, he was confirmed in the Methodist Church where he subsequently became the lay preacher. After two years at Blaauwbosch, he accepted a recommendation for a bursary to do a Higher Teachers’ Training Course at Adams College. He then spent the next 15 years of his life at Adams College.

At the end of his training course, he was offered a position to train African teachers at the College. Looking back at the life at Adam’s College, Luthuli laments the detachment from or rather ignorance about the harsh realities of the South African context. In 1928, in addition to his teaching responsibilities, Luthuli became the secretary of the African teachers’ association. He also took the initiative of founding the Zulu Language and Cultural Society auxiliary to the Teacher’s Association.[10] He also became the first secretary of the South African Football Association.[11] His abilities as a leader were thus already becoming manifest at that point of his life.

At some point, in the midst of his teaching work in Adamsville Luthuli was called back home by his people to become their chief.

Chief/ Traditional Leader

Luthuli reluctantly left his beloved teaching profession and accepted the call to chieftaincy after two years. Luthuli then became the chief of the Umvoti Mission Reserve.[12] He was able to bridge the gap between his people and the government on issues such as the building of white-owned beer halls among his own people. Although Luthuli had a resistant spirit, he chose to express it in a non-violent manner. Due to the previous non-violent, non-revolutionary passive resistance, Luthuli could not understand the government’s claim that there was conflict between his chieftaincy and his leadership of the African National Congress. He then called upon the government to give a precise definition of chieftainship.

Especially in his role as the president of the African National Congress, Luthuli stood up for the rights of his people, the dispossessed, the poor, and the voiceless. For this, Luthuli had to choose between his chieftainship and his rights as a man to fight for what he thought was good. He also knew that he might have to suffer for his choice even unto death.[13] Luthuli reasoned that,

I have embraced the non-violent passive resistance technique in fighting for freedom because I am convinced it is the only non-revolutionary, legitimate, and humane way that could be used by people denied, as we are, effective constitutional means to further aspirations. The wisdom or foolishness of this decision I place in the hands of the Almighty. What the future has in store for me I do not know. It might be ridicule, imprisonment, concentration camp, flogging, banishment, and even death. I only pray to the Almighty to strengthen my resolve so that none of these grim possibilities may deter me from striving, for the sake of the good name of our beloved country, for the Union of South Africa, to make it a true democracy and a true union in form and spirit of all communities in the land.[14]

Luthuli Politician

Hooper described Chief Albert Luthuli as a man with the following rare combination: “I think the paradox is this: the assurance is so deeply grounded in intellectual humility that it is not possible to distinguish one from the other. Neither quality would be there but for the other. Assurance without arrogance, and the humility of a man who cannot be humiliated: this is a rare combination.”[15]

Luthuli was involved for more than three decades in the resistance against white supremacy yet with no results from the government of the day.[16] The thirty years were typified by restrictive laws: no rights at all for South African Blacks, no adequate land for occupation, dwindling numbers of cattle, no decent and remunerative employment, restrictions on the freedom of movement through passes, influx control measures. The preceding measures were geared at ensuring and protecting white supremacy.[17]

The black South African Nobel Peace Prize laureates Luthuli, Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela did not choose to suffer, they were made to suffer. Suffering bred adversity, which bred character and then gave birth to a vision for social change. The first South African to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize was Chief Albert Luthuli in 1960.[18] The prize was awarded for Luthuli’s leadership of peaceful resistance to apartheid, noting the non-violence means he used to fight racial discrimination.

In his resistance however, Luthuli was not a passive Christian leader.

A Prophet and/or Activist Christian

Luthuli’s grandfather, Ntaba Luthuli, and his wife, Titisi, were the first two converts to Christianity in Groutville. Albert Luthuli regarded them as the founders of the Luthuli Christian line, and felt greatly indebted to them. Luthuli is remembered for his understanding of the sound relationship between church and state.[19] His political leadership and personal life were premised on the impulses and manifestations of Congregationalism. This strand of Protestantism had a major impact on his faith life.

While at Adams College, it became clear to Luthuli that the Christian faith was not a private affair irrelevant to society. “It was, rather, belief which equipped us in a unique way to meet the challenges of our society. It was a belief which had to be applied to the conditions of our lives; and our many works—they ranged from Sunday School teaching to road building—became meaningful as the outflow of Christian belief.”[20]

Luthuli confronted the apartheid system from the position of his faith by acknowledging that to “remain neutral in a situation where the laws of the land virtually criticized God for having created men of color, was the sort of thing [he] could not, as a Christian, tolerate.”[21] He also used the Bible to challenge the injustices levelled against the oppressed, the laws and conditions that debased a God-given force, that is, human personality. The laws might have been brought about by the state or other individuals but they were to be opposed relentlessly in the spirit of defiance revealed by St. Peter when he asked the rulers of his day: “Shall we obey God or man?” Laws and conditions debasing non-white people, abounded in South Africa.[22]

Chief Albert Luthuli’s Legacy for the African-South African Church

Christianity that is African

Contrary to what was taught by many missionaries in African contexts, Chief Albert Luthuli taught us that we did not need to deny and/or reject our African identity in order to be a Christian. Therefore it became possible to be an authentically Zulu Christian, for example. Each human being, irrespective of his/her culture or skin color, was valued by God, the Creator of them all. It is no wonder that Luthuli could at some point, albeit for a short period of time, perform his chieftaincy while unashamedly still adhering to and confessing his Christian faith.

Rejecting the False Dichotomy between (Christian) Religion and Politics

Contrary to the received theologies and biblical studies/hermeneutics, mostly devoid of cultural context in South African Church History, Luthuli believed that one’s religion (Christianity, in his case) should influence one’s political theory and praxis. Our Christian praxis must be revealed especially by how we treat those on the margins of our communities.

Luthuli, the preacher, also reminded believers that the Christian life is like an adventure. Like the apostle Peter, Luthuli called upon Christians to launch into the deep. How deeply one launched into the sea of Christian experience would, in Luthuli’s view, indicate how good and effective the blessing on humankind was. Just like Peter in the story upon which his sermon, titled, “Launch out into the deep: Christian Life as a Constant Venture” was based.[23]

Prophesying Truth to Power, Even at all Costs

Not unrelated to the preceding point, is the need for Christians, especially Christian leaders, be they teachers, lay preachers, politicians or chiefs, to speak truth to power, even if such speaking costs the prophets involved their own lives.

Madipoane Masenya (ngwan’a Mphahlele)

Notes:

- Paton 1967, p.207.

- Luthuli 1962, p.19.

- Luthuli 1962, p.23. Looking back at the disciplinarian mother who brought him up basically as an only child, he was grateful.

- Luthuli 1962, p.24.

- Luthuli 1962, p.25.

- John De Gruchy lists the following key impulses of Congregationalism: a key commitment against state interference in the church; a democratic church order in which property ownership and decision making are in the hands of the local congregation; a commitment to unity and ecumenism; a valuing of human dignity, justice and freedom as key elements in its praxis in the world and a desire to share its message around the world (De Gruchy, n.d. 5, African Studies 701, April 2011).

- Cf. Ohlange Institute and Edendale, 1962, p.29.

- Luthuli 1962, p.29.

- Luthuli 1962, p.29.

- Luthuli 1962, p.34-35.

- Luthuli 1962, p.35.

- Luthuli1962, p.50-51.

- Paton 1967, p.207.

- Luthuli 2008, p.114-115.

- Luthuli 1962, p.12; Charles Hooper, p.9-14.

- Luthuli 1962, p.15.

- Luthuli 2008, p.112.

- Irwin 2009, p.158.

- Luthuli 1962, p.20.

- Luthuli 1962, p.39.

- Luthuli 1961, p.162.

- Luthuli 2008, p.114.

- Luthuli 2008, p.110.

Bibliography:

Luthuli, Albert. Let My People Go: An Autobiography. Introduction by Charles Hooper. Glasgow: Fount Paperbacks, 1962.

Luthuli, Albert. “The Road to Freedom is Via the Cross.” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 130 (2008): 112-115.

Luthuli, Albert. Documentation: Albert John Luthuli, “Launch out into the deep: Christian Life as a Constant Venture,” a sermon preached at Adams College, at the morning worship service, Sunday, November 09, 1952. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 130 (2008): 180-111.

Paton, Alan. “History Will Make His Voice Speak Again: In Memorium: Albert Luthuli.” Christianity and Crisis, September 18 (1967): 206-207.

Irwin, Darrel D. Unorthodox Criminologists: A Special Issue- Part III; Awards for suffering: the Nobel Peace Prize recipients of South Africa, Contemporary Justice Review, Vol 12/2, June 2009, 157-170.

This biography, received in 2017, was written by Prof. Dr. Madipoane Masenya (ngwan’a Mphahlele), professor of Old Testament Studies in the Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies at the University of South Africa, DACB advisor and JACB contributing editor.