Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Mbhele, Julius uMkomazi

Julius uMkomazi Mbhele was born in 1879 into the Amabela tribe. He was received into the mission station at Lourdes in 1894 and baptized in 1896. Following his baptism Mbhele applied for permission to train as a priest in 1896. Four application letters were sent to Rome from the Vicariate of Natal for four boys to be trained as priests. The following year rinderpest, a deadly cattle sickness, broke out and swarms of locusts devastated the mission lands and fields at Lourdes. [1] Meanwhile, the application letters came back in the same year. Although they were all accepted, two of the boys withdrew, leaving Andreas Ngidi and Julius Mbhele as the only candidates for the priesthood.

A particular incident that encouraged Ngidi and Mbhele’s vocation to the priesthood is related by Ngidi as follows:

In the meantime, in 1898 the first African South African priest, Dr. Edward Mueller, arrived in Durban and visited some of the mission stations; in Centocow Andrew saw him celebrating Holy Mass and he served mass. All that went to confirm his vocation and gave him more courage. If this African went to Rome and came back as a priest, why not I? Of all the Mariannhill Mission stations only Lourdes in Griqualand East answered the call and Julius Mkomazi–our Rev. Dr. Julius Mbhele–became available to go with Ngidi overseas.[2]

Departure for Rome

Andreas Ngidi and Julius Mbhele left for Rome on September 22, 1899, just two days before the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War. They stayed there for eight years and were quite successful. Ngidi and Mbhele both received doctorates in philosophy and, in addition, Ngidi completed a doctorate in theology. Soon, the fulfilment of their most ardent desire arrived: the day of their ordination to the priesthood in the Lateran Basilica by Cardinal Respighi, the vicar of Rome, on May 25, 1907. Both said their first masses the next day, “the Rev. Julius Mbhele, being the dean of the class, in the chapel of the Propaganda College; while Father Andrew Ngidi chose to celebrate his first mass in the German national church, del anima, for he had great love and gratitude for the German missionaries in his country…Shortly before, their group had been received by the Holy Father Pope Pius X.”[3]

Before returning to South Africa, they visited Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and England, arriving home in 1907.[4] After their return, the two priests were assigned to different missions in the vicariate of Natal. Ngidi worked at Keilands, Lourdes, and Cassino mission stations.[5]

On his return from Rome in 1907 until 1924, Mbhele was involved in mission work at Mariannhill. In 1910, while working at Mariannhill, Mbhele was incarcerated at Einsiedeln, near Eston (between Richmond and Ixopo, KwaZulu-Natal) and was not allowed to practice as a priest. Mbhele had problems staying at any mission because of his differences with the rectors and the bishop of Mariannhill. Hence in 1910, he wrote a letter to the abbot in which he said:

Now I beg to ask what will become of me when the station will be transferred to Inhlazuka as I understand there is no room there. But even if there were room, I would still ask how long will my incarceration last? Of course, you have made your appeal to the bishop about this, but I still fail to see how he comes in now in this matter while he was not required for my incarceration here. Once defamed in one place I do not believe in being forced to defame myself or at least to confirm my defamations in another place by staying in a mission without working as missionary, as it has been the case so far. I think what I am asking is only reasonable in as much as I ask what everybody would ask being in a similar condition as I am in. The letter of his Lordship has left me first in the dark since I do not know anything definite now just as I did not know before.[6]

The reasons for his incarceration are not stated in the letter.[7] However a later letter from the Abbot of Mariannhill, Fr. Gerard Wolpert, CMM, hints at the possible reasons that seem to involve a breach of trust:

If he proves himself worthy of the trust, and avails himself, in the right spirit, of the opportunity offered, so much the better. If not, well, any arising mischief can be stopped ere it is too late, and any future complaints from his part can be silenced easily…. I think there is something in what Father Solanus said, and I therefore submit his proposal to your Lordship’s consideration or similar conditions, viz.:

1) Your Lordship should tell Father Solanus that he will be responsible for the good behavior of Father Julius, that he will have to watch carefully over him and the work he will be given, and that he has to report conscientiously every month on the behavior of Father Julius.

2) Father Julius should be informed that he is given this opportunity in order to show that he has tried to mend, and that he is willing to do so more and more, that however he cannot be given another chance should he prove himself unworthy of the trust reposed in him now.[8]

His Early Pastoral work in Mariannhill

While working in the Mariannhill diocese he tried to protect the people who had been converted to Catholicism so they would keep their faith as Fr. Baldwin Reiner CMM wrote in 1909:

I was astonished to receive a letter from your Lordship in this matter, as I was under the impression that Father Julius was somewhere in Pondoland, but not in Lourdes. He had asked the Right Rev. Father Abbot to allow him to go to Pondoland and fetch his sister, whose husband had died, and who was now staying alone among heathen people. He was given permission and told to be back at Mariannhill at the latest in three weeks after his start from here, which he himself thought quite reasonable time.[9]

After his incarceration at Einsiedeln Mbhele was involved in teaching catechism and saying mass for Zulu Catholics as suggested in a 1911 note by Fr. Gerard Wolpert CMM:

With regard to the above [Fr. Julius Mbhele]… I beg to make the following proposals:

a) that I be empowered to send Father Julius, as occasion arises, into the one or other good kraal with the injunction to give catechetical instruction there.

b) that I be empowered to send Father Julius occasionally to “Inhlazuka” and “Amaneus Hill” for the purpose of saying mass and giving catechetical instruction.

c) that I be empowered to let him preach on (alternate) Sundays at “Einsiedeln” and let him hold catechetical instructions there regularly on Sundays.[10]

The Farm

In the early 1920s, Mbhele bought a farm near Ncala Mission. This he did for two main reasons: First, he felt that, since he was being ill-treated at several mission stations in Mariannhill, it would preferable for him to buy a farm. Thus, if he had to leave the priesthood, he would still have a home. Secondly, he wanted his farm to be a base for future ministry among the Zulu people.[11] As Mbhele states: “These farms may serve as bases for future mission work when the native priest will be able to take charge of the work just as Mariannhill contends that they need farms to that effect and the bishop himself had declared to you that we could not be put in charge of their properties since we are outsiders.”[12]

In 1922 Fleischer was elected bishop. Two years later, Bishop Fleischer wrote an angry letter to Mncadi (the third African priest to be ordained in South Africa), on the subject of his farm in which he mentions Mbhele.[13] By the end of 1924, Mbhele was transferred to St. John’s parish in Umgodi where he worked for two more years. The farm became a major concern for Bishop Fleischer who, in 1924, tried to force both Mbhele and Mncadi to sell their farms. He wrote a letter to Mbhele in which he suspended him and asked him to dispose of the farm:

As you today declared before me, Father Superior here and Father Aloys Mncadi that you did not try nor are willing to do so in future, to dispose of your farm. Although I ordered you under the 4th of September this year to do so before this Christmas, I suspend you from saying holy mass. At that 4th of September I declared to you that I hold it a duty of conscience to give you that order. On the 6th again, on the 7th of the month I repeated it saying you are on the way to hell by your continued stubborn disobedience to your bishop who wants to save your soul by order. P.S. I told you next month you have opportunity to put your case before the apostolic delegate who comes here.[14]

The priests believed he was depriving them of the right to own property. The bishop’s contention, however, was that farm ownership among indigenous priests could be open to abuse; according to the priests this was not borne out by the facts. For example, Mncadi had been in possession of a farm for more than ten years and nobody complained about that matter, nor was the situation abused. Mbhele refused to sell the farm. He took up this challenge head-on and challenged not only the bishop, but even the apostolic delegate about his right to own land.

In November 1924, Mbhele and Fr. Andreas Ngidi (the actual author of the petition), formulated a petition entitled “Farm-ownership by Native [diocesan] Priests in South Africa”[15] which was sent to Archbishop Jordan Bernard Gijlswijk,[16] the apostolic delegate, requesting the right to continue owning farms. Mnganga was reluctant to sign it. A copy that exists of this petition shows only the signatures of Ngidi and Mbhele, however this was in all probability a copy produced before the petition was finalized, and the other two priests may have signed it later. The introduction of the petition states that the native [diocesan] priests of the Mariannhill Vicariate were concerned and alarmed at “the attitude our beloved bishop is taking towards us in general and Mbhele in particular.”[17] Seven points are put across for the delegate’s consideration, inter alia: that the priests were being forced to sell their farm; that farms could be abused by black priests; that canon law supported land ownership, and that the farms were bought before the bishop had been nominated.[18]

The three priests (Fr. Alois Mncadi, Fr. Julius Mbhele, and Fr. Andreas Ngidi) managed to arrange an interview with the apostolic delegate, Giljswijk.[19] During this interview the delegate stated inter alia that “even from the beginning to the end, that there was no question about your right in possessing the landed property [and] even your bishop did not…deny that you have that right.”[20] He went on by stating that although they “have freedom as far as the possession is concerned, but in regard to the exercise of your right upon it, the bishop might have to interfere with it, and rightly for certain he could and can transfer you from the place nearest to your farms to a far distance.”[21] Giljswijk glibly added that, suppose “the bishop sends you to Pondoland! How then could you exercise your rights in it?”[22]

The delegate also wrote back saying that according to Canon 127 and 142, a priest was supposed to obey his bishop when commanded. Not much was achieved through this petition, however.

Although Mbhele was incurring the wrath of his superiors, he did not receive support from his fellow black priests. For example, on the reaction of Alois Mncadi to the issue of farms, Mbhele wrote:

I cannot understand Father Alois, he seems to imagine that because he is only nominally the owner of that farm at Mhlabashana, this farm is my personal concern. I explained the whole situation to him but till now I got no answer from him, while to the explanation I had given him before he went to Mariannhill he replied by heaping blames against me as if I was fighting for direct administration of the farm instead of leaving this to others. Even if that were the only aim I had it would be unreasonable seeing that I must see to it that the farm is beneficially used so as to pay the installments for itself. It is a pity to have to cooperate with a man who changes like the moon.[23]

Mnganga, on the other hand, refused to help or cooperate for the reason that he was under the Natal Vicariate. He wrote:

As personally concerned I am working under Natal Vicariate, not under Mariannhill, thus not implicated in the present affair. Moreover, his Lordship Bishop Fleischer wrote his statement concerning the farms of only two native priests, thereupon mentioned, why should we all four sign a retaliating letter to the delegate apostolic?[24]

Mbhele did not welcome such reasoning. For him, these were no reasons at all. He had a universal approach in the sense that, if a problem affected an indigenous clergyman at the present time, then it was quite possible that it would affect any future indigenous clergy as well. So it had to be addressed by all indigenous clergy, in order to set a precedent for indigenous priests in the future. As he explains:

This can be seen from the order of His Lordship which says “I think a farm is a very dangerous thing for a native priest” and from His pointing to the bishop of Uganda. Will they not use the same cavillation in Rome? Of course this is no argument against the universal law which is in favor but what if they were to say: Oh no! We do not intend to exclude the African priest from exercising the right for all time, only these of the present generation for the reason that they are not yet in a position to take charge of the work among their people, etc…[25]

Bible Translation Work

In 1927, Mbhele was transferred back to the monastery (Marianhill). During this period he wrote a great deal for the local newspaper, Izindaba Zabantu [26] and was involved in the translation of the Bible. As Mncadi wrote:

As his Lordship has an exceptional talent in the person of A. N. (Andreas Ngidi) and J. M. (Julius Mbhele), especially the intellectual gift of Rev. Mbhele, he might use them for translating the New and Old Bible into Zulu. These two are the best in the whole South Africa even I may in all earnestness and fairness say that they are the best and unique machinery for that purpose in the sub-continent.[27]

In 1930, he was also given works of Goffine to translate. Leonard Goffine (b. 1648; d. 1719) was a German Catholic Monk belonging to the Norbertine Order. Bishop Sprieter wrote:

Thanks for your kind letter about Rev. Fr Julius. He arrived well and he says he is happy here…. Long before Rev. Julius arrived I had decided to give him for translation the book Goffine. He is already working on it and a little walk he makes with Father Andrew. So I trust with grace of Almighty God thing[s] will be alright.[28]

Troubled Times

In 1933, Mbhele left Mariannhill and joined the Zululand Diocese to work as a diocesan priest. He worked at Inkamana for a year and the following year was transferred to Entabeni. In Zululand he experienced similar problems related to his farm. Between March 1933 and October 1937, Bishop Spreiter wrote numerous letters to Mbhele concerning his farm near Ncala Mission. We will see that there were other allegations, too, which the bishop brought forward, concerning Mbhele’s perceived involvement with women and drinking.[29] On March 30, 1933, Mbhele replied to the letter from Bishop Spreiter in which the bishop had stopped him from saying mass and demanded once again that he sell the farm. He wrote:

I do say holy mass here not for the people. I consulted a certain professor on this matter and he wrote back, “…saying holy mass in a private residence occasionally when the church or chapel is four miles or more away does not need any permission.” The prohibition in this case is manifestly unjust and such being the case I am bound to appeal to higher authorities. As to selling the farm, I have no intentions of doing so for the reason that it was the ill-treatment I always received at the hands of the Mariannhill authorities which made me think of buying the farm.[30]

Seven months later another incident occurred, in which Mbhele was once again threatened. If he refused to do what the bishop said, he was to be sent back to Mariannhill. Bishop Spreiter wrote to Mbhele saying:

Yesterday I heard that you on Friday have been in Vryh. (Vryheid) until twelve o’clock and that you have brought the case of Martin (?) about the thirty silverlings (Judas) to the court. I don’t know what is the truth about it but if so as reported, then it is a real cause to feel indignity…. Dear Father I adjure for the sake of the salvation of your immortal soul, be careful. Do not force me to send you back to your bishop. You know that your future will be ruined. Somebody said about you: you are the most intelligent[31] of the four Native priests but also the most imprudent. You are too proud.[32]

After 1935 there was a series of accusations about Mbhele’s farm. Bishop Spreiter received numerous letters concerning Mbhele from Sixtus Wittekind, a priest at the Ncala mission station. On March 27 of the same year, Mbhele received a letter from the bishop which accused him, inter alia, of having a divorced woman living with him in his house, and that he had bought a barrel of wine and taken it to his farm. The bishop therefore ordered him not to go to the farm until the truth was established. “Your honor as a priest demands too, that you are not going to the farm.”[33]

In response to these accusations, Mbhele sent a long letter explaining that these were all misconceptions and it was a personal vendetta of Sixtus Wittekind. He argued that, since Sixtus was always showing such delicacy of conscience about casks of wine, “Can he maintain with all conscience-if he has any-that in the whole of his vicariate there is not a single priest who drinks? Who are those friends to whom I gave wine? Who are his informers? I want their names now.” [34] He continues:

“That woman was there”–does he want to repeat the same lies that she lives in my house? If he is a bonus pastor, as he pretends to be, why is it that he never tried to convert his erring sheep instead of using her as a weapon against me behind my back? On the contrary, when I at last succeeded in persuading her to go to him, instead of receiving her like a good shepherd, he drove her away saying that he did not like even to see her. Thus it is clear that he wants to hear one side only, and that only which is damaging to his neighbor. [35]

Mbhele claimed to have some proof that Sixtus employed spies. For example, on March 12, 1936, a young woman came to his farm apparently sent by Sixtus. She pretended to want confession the following day. She never arrived on March 13, but instead wrote a letter to Sixtus on the state of affairs at the Mbhele farm. According to Mbhele, she was, “…well known to be a spy, and one of the worst characters.”[36] Mbhele also stated in his letter to the bishop that Sixtus not only wrote down what people told him spontaneously and employed spies but also went “so far as to interrogate people…in the confessional.”[37] He did not even determine whether these allegations were true or false but immediately wrote to his bishop.

The trouble between Sixtus and Mbhele had started almost twenty years previously. As Mbhele wrote:

Some twenty years ago, when I had the misfortune to be with him at Reichenau, he did not mention what he did against me then, but only told of the trouble I gave him about utshwala (beer), which, by the way, was a mere fabrication of his. When I saw that it was impossible to stay any longer with him, I simply left for Mariannhill. Since then several young fathers have been sent as assistant to him…but none of them has found it possible to stand (him).[38]

Ever since Mbhele had left Mariannhill, Sixtus had tried to get hold of isigaxa, which means some information to harm Mbhele’s reputation. But, since he could not find any, according to Mbhele, he fabricated a story. On the other hand, Sixtus said that Mbhele had told people at Reichenau that Sixtus had been married before he came to South Africa. The superior asked Mbhele about this and he replied, “What! Was Father Sixtus ever married?”[39]

The issue of the farm had been a big problem from 1924 onwards. According to Mbhele, Sixtus travelled past his farm in 1925 and commented:

Coming from Maristella M. S. where it had been decided to compel the late Father Alois and myself to dispose of our farms, he passed my place, and admiring it said “Au! Kanti lihle kangaka, alimfanele; sengati kungaba elemakosana ansundu. Sizobona, uzolilahla.” Which roughly translated means “Ah! What a beautiful place! It is too good for him. It would just be the place for the Native Sisters (and therefore be in his charge). We shall see to it that he loses it. ‘Invidia clericalis!’“[40]

According to Mbhele, Sixtus made some grave mistakes. First, he accused Mbhele of saying mass in 1932 in front of a gathering of natives while suspended. Sixtus also abused the confessional and announced in church that because he was too old and sickly, people should not come to him with sick calls. As a result of this some people died without receiving the last sacraments. In addition, Sixtus was summoned to court because he had tampered with other people’s private correspondence. As Mbhele continued: “How did he extricate himself from his unenviable position? I am told that he instructed a boy to tell a lie in court in Father Sixtus’ defence by saying that it was he, the boy, who had opened the letters.”[41]

Sixtus sent numerous accusations to the bishop about Mbhele, stating that he had come with a Monsignor Arnoz and found Mbhele in a compromising situation. He claimed that “there were drinking-bouts nearly every day, also brawls. The prestige of the Amaroma (the Roman Catholic Church) is sinking down such orgies.”[42] In reply, Bishop Spreiter said that Mbhele’s allegations about the abuse of the confessional by Sixtus was a serious matter, as he knew that many natives did not speak the truth. He advised him again to sell the farm and put the money in the bank. To some of these Mbhele replied:

It seems that Father Sixtus is trying to enlist Your Excellency’s influence to compel me directly or indirectly to yield to Mariannhill’s desire that native priests should have no farms. Hence he is trying to make out a farm as the source of all evil, but he forgets that I know all the great scandals some of Mariannhill members have given from its foundation till now and these scandals are not few. Are these scandals caused by the farm? [43]

The visit with the monsignor, Bishop Spreiter, also conveyed the message that the monsignor supported the claim that owning a farm was a bad thing.

On the case of finding him in “a situation” with a woman, Mbhele wrote that he sued Sixtus and the monsignor in a court of law but lost the case. As he says: “…and they did not find me in that situation as he says, otherwise it would have been very foolish of me to sue them and they would have not found it necessary to engage a lawyer as they did. To lose a case is not always a proof of guilt.”[44]

Mbhele then goes on to give an example of a missionary priest who was actually found in a similar compromising situation with a woman.

In the same year this same Father Sixtus was sent with other two priests to a certain mission station to investigate the charges brought against a certain priest already well known to be a concubinarius who had a regular harem on the mission station itself. He was not visited at night time, but was informed a week before hand, of the coming visit and since one of the said harem was already in a family, the parents having failed to obtain justice at Mariannhill, they brought the matter to the local court. The said priest was reinstated in the same mission as if nothing had happened. The magistrate had to intervene, it was only through this intervention that the said missionary was sent to Europe. Suffice to mention this glaring case out of many.[45]

In this letter, Mbhele alleged that the parishioners had petitioned the bishop to remove Sixtus, because he refused to do his job. But Sixtus still continued to send letters of complaint to the bishop,[46] to the extent that in 1935 Spreiter wrote a letter to Mbhele asking him to solemnly declare that he was not living with the woman. On October 16, Mbhele replied saying:

I solemnly declare before almighty God that the woman in question has never lived in my house but always lived with her children in a house in which other people were living. She applied and was accepted by me as a tenant like others but since she has no one to pay her rent for her I gave work of sewing. There is nothing wrong.[47]

Mbhele believed that Sixtus’ aim was to literally destroy him by employing spies against him. In one of his letters to the bishop, Sixtus clearly states this intention when he says:

As I always did, when R. F. Julius was still under our bishop, so I wish to do now if I get no advice to the contrary. The thing I reported was: wine is on the way to R. F. Julius’ farm. A consignment note in open envelope has arrived again dated 25/11/36 from a Durban firm…for wine to the amount of £1-13-0, sent to St. Anthony’s…If it is agreeable to get such notification, the way how it is discovered must not be revealed, or better, no mention at all must be made of wine.[48]

This letter indicates that Sixtus was either employed as a spy by the previous bishop, or had himself appointed someone to spy on Mbhele. It is indeed very difficult to really know what really happened between Mbhele and Sixtus. Oral testimonies on this matter are unavailable, the only sources available being in the archives. The important point however is that we are presented with opinions and facts from both sides.

His work in Zululand 1933 to 1937

Mbhele did some good work among the Zulu people by encouraging them to practice their faith. In trying to encourage a woman who was not receiving holy communion, Mbhele wrote in 1935:

The woman Fr. Sixtus is writing about is staying [at my farm. Saying that she is] a fallen away Catholic is not true. She had married a protestant who had a wife therefore she wants to divorce him and thus be able to receive the Holy Sacrament again. What I found out this last time was that ever since she came to the place she never went to church. This I was told by her. I impressed upon her the duty of going to church.[49]

In other instances he became too attached to his mission station and refused to be transferred. For instance, while stationed at Entabeni mission, Bishop Spreiter requested that Mbhele be transferred to Mbongolwana. To this request Mbhele responded: “With reference to your note…I beg to point out that for certain reasons I feel reluctant to go to Mbongolwana and therefore humbly pray your Excellency to allow me to remain a little longer here at Entabeni.”[50] Bishop Spreiter did not understand Mbhele’s request and demanded an explanation and an early reply to his request.[51] Some of these misunderstandings led Mbhele to leave the Zululand diocese.

Leaving Zululand Diocese

As a result of the problems between Bishop Spreiter, Mbhele decided to leave the diocese of Zululand at the end of 1937. He went to stay at his farm for a year. However, since he still wanted to work as a priest he did not like to stay on the farm, and said that, although, materially, he could be as free as a bird,[52] it was “not conducive to the salvation”[53] of his soul. In December 1938, Bishop Spreiter wrote a letter to Bishop Romuald M. Migliorini, the Vicar Apostolic of eswatini, a Servite of Italian origin, recommending Mbhele. He stated:

Repeatedly being asked by Exc. Bishop Fleischer, Mariannhill, I consented to take the three Native priests from Mariannhill to Zululand, in order to help the bishop. One of these three died, one is still with us and Rev. Julius Mbhele I have dismissed on the 12th Dec. the reason was that he molested women and a girl. He did not the worst. But the people has been angry about [sic], and that the more, as one of our brothers on the first of November has left the Mission for peccata contra sextum, on the same very mission. Therefore I have been obliged to dismiss him. As he wrote, he will save his soul, he will not remain there. I think he has a right. Julius belongs until now to the Vicariate of Mariannhill. Rt. Bp. Fleischer has several times asked me to take him over in my vicariate, but I could not do that, fearing that one day troubles will arise.[54]

From the letter, we see that Bishop Spreiter briefly summarized the problems Mbhele had experienced in Mariannhill and Zululand. In addition, he cautioned Bishop Migliorini that having black priests in his country might create problems, stating: “To see a black priest on the altar would perhaps develop among your boys the desire to become also a priest.”[55]

In 1939, Mbhele went to eswatini and worked at Bremersdorp for six years. In 1945, he was transferred to Mbabane in eswatini, where he worked until the early 1950s, before returning to retire on his farm near Ncala Mission shortly before his death in 1956.

George Sombe Mukuka

Notes:

-

For a full discussion on the epizootia of rinderpest see Benedict Carton, “Blood from your Sons: African Generational Conflict in Natal and Zululand, South Africa, 1880-1910,” (Unpublished PhD. Dissertation, Yale University, 1996), 153-161.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1 no. 9, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

The autobiography ends with their arrival in South Africa. The other information on where they worked and what transpired is from oral interviews and archival material. See also, “Ein freudiges Ereignis,” Vergissmeinnicht 63, (1907), 194.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Clergy, “Julius Mbhele’s Letter to Right Rev. Abbot,” Einsideln, November 30, 1910.

-

See, Durban Archdiocesan Archives, “Letter by Mbhele to the Abbot,” Einsideln, October 31, 1910.

-

Durban Archdiocesan Archives, Letter by Fr. Gerard Wolpert CMM to the Right Rev. Bishop H. Delalle OMI, Maritzburg, January 14, 1911.

-

Durban Archdiocesan Archives, Letter by Fr. Baldwin Reiner CMM to the Right Rev. Bishop H. Delalle OMI, Maritzburg, November 30, 1909.

-

Durban Archdiocesan Archives, Letter by Fr. Gerard Wolpert CMM to the Right Rev. Bishop H. Delalle OMI, Maritzburg, January 14, 1911.

-

See Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter from Mbhele to Ngidi,” Umgodi, November 23, 1924.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Julius Mbhele, Letter to Father Andreas Ngidi,” Umgodi, via Highflats, November 7, 1924.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Priests, “True Copy of Bishop Fleischer Letter to Aloys Mncadi,” Mariannhill, December 28, 1924. Here is the text of the letter dated December 28, 1924 in which Bishop Fleischer ordered Mncadi to sell the farm forthwith and also suspended him from his priestly duties:

Under the 4th September this year I ordered you to dispose of your farm before Christmas, because the possession of your farm will one day became a great danger to you of not listening to your bishop and risking eternal damnation whilst you need no farm as the bishop will care for you paternally as long as you are his loyal priest. On 28th of November I reminded you of your duty, but you answered by two very irrelevant letters to say not more. At the same time you wrote a very bad letter to Father Julius Mbhele. in which you try to undermine the authority of the Bishop. I upon this suspend you from saying hl (holy) mass. Now today before me Father Superior and Father Julius Mbhele you declared that you did not try nor are willing to do so in the future, to dispose of your farm. I shall put your case before the apostolic delegate.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Clergy, “Aldabero Fleischer, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Mariannhill, September 28, 1924.

-

For a full discussion of the apostolic delegate see, Denis, The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa.

-

Jordan Bernard Gijlswijk (1870-1944) was appointed apostolic delegate in 1923 until he died. For a full discussion on Gijlswijk see Philippe Denis, The Dominican Friars in South Africa: A Social History 1577-1990, (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 147-201.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Petition to His Excellency, Archbishop Gijlswijk Delegate Apostolic, ‘Farm ownership by Native Secular Priests in Africa’,” n.d.

-

There are the seven points elaborated in the petition:

1) His Lordship Bishop Fleischer was forcing the Reverend Fathers A. Mncadi and J. Mbhele to sell their farms, and this seemed to deprive the native secular priests of the right to own property.

2) The bishop’s contention that farm-ownership among native priests could be open to abuse was not borne out by the facts, as the Rev. A Mncadi had been in possession of one for more than ten years and nobody had ever had reason to complain about that matter.

3) In the case of Rev. J. Mbhele, no argument could be made, because it was His Lordship himself who made it impossible for Mbhele to stay at any other Mission of Mariannhill after their differences at Mariannhill. Even if it could be construed that the farm was in any way involved in the matter, that would only concern the abuse and not farm-ownership itself.

4) They feared that the general prohibition on the native secular clergy owning land was an arbitrary and wanton use of superior power not warranted by both Divine and Canon Laws, which allowed secular priests to own property.

5) European missionaries were allowed to own land in Africa and everywhere else. Only the African priests were prohibited from ownership in their mother country. Did this discrimination not smell of the colonial color bar policy?

6) As the facts and experiences failed to carry weight with His Lordship in the above matter, all four most reluctantly found themselves having to work as missionaries at the stations of Lourdes, Centocow, Mariathal, St. Michael, Himmelberg, St. Johannes, and Maria Trost. They declined to submit to his Lordship’s order, as being “ultra vires”’ unjustified and un-canonical and, therefore…begged the apostolic delegate to intervene and indicate to them what course of action to take under the circumstances.

7) In conclusion, they stated that both these land transactions were concluded before His Lordship’s nomination and consecration, thus rendering all his actions… impossible of a retrospective affect.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Aloys Mncadi, Letter to Andreas Ngidi,” Mariannhill, February 18, 1925.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “Letter from Bishop Spreiter to Bishop Romuald M. Migliorini,” Inkamana December 20, 1938.

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Clergy, “Edward Mnganga, A Letter to Julius Mbhele,” November 10, 1924.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to Ngidi,” Umgodi, November 21, 1924.

-

See articles, UmAfrika, “‘Kuka’ Kam nenzalo yake,” (April 17 and 24, 1925).

-

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Clergy, “Aloysius Mncadi, A Letter to the Bishop,” Maria Trost, via Highflats, March 13, 1930.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Letter from Bishop Spreiter to Mncadi” Inkamana, March 25, 1930.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Letter from Bishop Spreiter to Mbhele,” Inkamana, June 5, 1937.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to the Excellency Thomas Sprieter OSB, St. Anthony’s,” P. O. Incalu, March 30, 1933.

-

This fact was also attested by Aloys Mncadi, when he wrote to Bishop Thomas Spreiter, saying, “As His Lordship has an exceptional talent in person of both Reverend A. N and J. M., especially the intellectual gift of Rev. Mbhele he might use him for translating the New and Old Bible into Zulu. These two are the best in the whole of South Africa even may in all earnestness and fairness say that they are the best and unique machinery for that purpose in the sub-continent.” Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Letter from Aloys Mncadi to Bishop Thomas Spreiter,” Maria Trost, March 13, 1930.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, A Letter to Father Julius,” Inkamana, October 1, 1933.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, A Letter to Father Julius,” Inkamana, March 27, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele, A Letter to His Excellency Bishop Th. Spreiter O.S.B, Gonzaga,” P.O. Qudeni Zululand, April 20, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana Mission, Vryheid, April 16, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana Mission, Vryheid, April 16, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Julius Mbhele to Bishop Spreiter, Cach Mission Entabeni,” April 23, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Clergy File #1, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana Mission, Vryheid, April 16, 1935,

-

See Archives of Inkamana Monastery, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Mission Inkamana, October 8, 1935; “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Herr P. Sixtus Wittekind,” Mission Inkamana, October 9, 1935; “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Herr P. Valentin,” Inkamana, October 9, 1935; “Julius Mbhele, Letter to Thomas Spreiter Bishop,” Catholic Mission, Entabeni, October 11, 1935; “Julius Mbhele, Letter to Thomas Spreiter Bishop,” Catholic Mission, Entabeni, 12 October 1935; “P. Sixtus, Letter to Bishop Spreiter,” Zululand, October 13, 1935. “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Mission Inkamana, October 14, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Letter to Father Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana Mission, October 14, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “F. Sixtus, Letter to Right Rev. Bishop Spreiter,” Eshowe, Mary-Help M. S., Incalu, Ixopo.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Fr. Mbhele, Letter to Thomas Spreiter, Bishop, Entabeni Mission, October 12, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Julius Mbhele, Letter to Thomas Spreiter, Bishop,” Catholic Mission, Entabeni, Gingindlovu, July 27, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Letter from Thomas Spreiter, Bishop to Julius Mbhele,” Inkamana, July 30, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Julius Mbhele, Letter to Thomas Spreiter, Bishop,” St. Antony’s, Incalu, Ixopo.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Thomas Spreiter, Letter to Right Rev. Mgr. Romauld M. Migliorini OSM, Prefect Apostolic,” eswatini, Inkamana, December 20, 1938.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Spreiter (26) African Priests, “Thomas Spreiter, Letter to Right Rev. Mgr. Romauld M. Migliorini OSM, Prefect Apostolic,” eswatini, Inkamana, December 20, 1938. The letter continued saying that, “Julius is, so far I know over fifty years of age, and the fire in the flesh, perhaps will go down. In all the about ten years and more I had only once a little difficulty with him, and since he was always a good old priest. He has no powerful voice since he is slowly, and not very healthy. I would ask you to help him in so far-when Bishop Fleischer has no objection-to make a test with him and to tell him, if this test will be a failure, that he has to leave at once….The native priests have been with us, as in Mariannhill, in the Refectory, and had their own rooms. They got nor other money from us as the stipends for masses, mostly each mass with a dollar.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, “Letter from Bishop Spreiter to Bishop Romuald M. Migliorini,” Inkamana, December 20, 1938.

Bibliography

Archbishop of Durban Archives, File on the First Black Clergy.

Durban Archdiocesan Archives.

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1.

Philippe Denis, The Dominican Friars in South Africa: A Social History 1577-1990 (Leiden: Brill, 1998).

UmAfrika, “‘Kuka’ Kam nenzalo yake,” April 17 and 24, 1925.

Vergissmeinnicht, (1907).

This article, received in 2008, was written by Dr. George Sombe Mukuka, a faculty research manager at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and 2008-2009 DACB Project Luke Fellow.

Photo Gallery

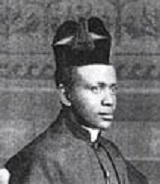

[1] Mbhele, seated. Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1908), 219.

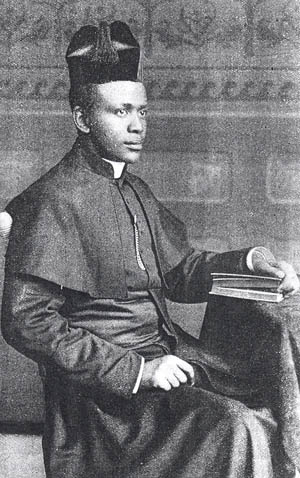

[2] Four first black priests: Ngidi, Mncadi, Mbhele, and Mnganga (seated). Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1924), 251.

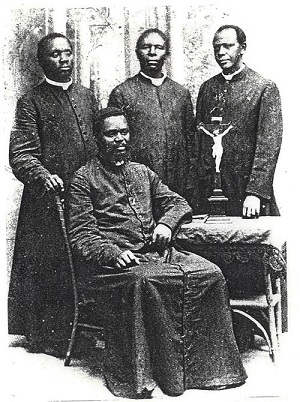

[3] Mbhele with children. Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1908), 200.

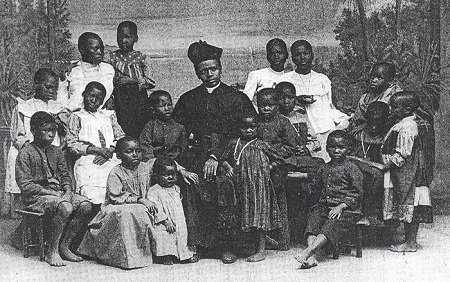

[4] Msgr. Gijlswijk (center) with Bishop Fleischer (right). Photo from Vergissmeinnicht (1945), 76.