Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Ngidi, Andreas Mdontswa

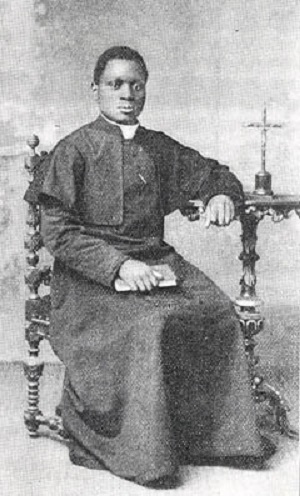

Andreas Mdontswa Ngidi was the third black Catholic priest in South Africa.

Andreas Mdontswa Ngidi was the third black Catholic priest in South Africa.

Ngidi was born in the year 1881, not even a decade after the 1879 Zulu War and soon after the capture of King Cetshwayo of Impande. His father, Mbhemiwegudu Ngidi, had three wives, the third of whom was Nomakholwa Ndlovu. She had two sons, Mdontswa and Mbhelekwana. Mbhemi’s early career was that of an ox-wagon driver working on the route between Durban and Johannesburg [1], and it is believed he was very strong. Ngidi said:

It is said that he was so strong, that down Donlsamfana mountain (near Inchanga Railway Station)-finding it impossible to stop the wagon-he would take off the hind wheel with one hand, and get the team down safely. Once more it is said that some German settlers near Botha’s Hill got into trouble with him, their oxen having trespassed on his mealie field. Mbhemi would go out single-handed to fight it out, when old Mabuyabuya, his father, would call out to his other sons to hold their brother back and not cause more damage and bloodshed. [2]

In 1886, Mbhemi took his third wife, Ma Ndlovu, and her two children away from his Denge Kraal to Donkvlei between the Inkonzo and Umzimkulu Rivers, under the Mondi Mountains, on the main road from Durban to Kokstad in Griqualand East, Cape Colony. He then left for Pondoland, selling medicine for many years. Ma Ndlovu had to stay with her relatives near Inondi Store at Manzomphofu until her two boys had grown up. She helped her brother, Nkotheni ka Cimbi Ndlovu, looking after his cattle, horses, and goats along the slopes of Mondi Mountains. The encroachment of the European settlers into Natal adversely affected the Ngidi family.

Ngidi’s uncle, Nkotheni, had remained under Chief Mqandane Mlaba, or Ximba, who was chief of the whole of the Cekwane Valley since 1886. But the time had come when the Africans were to give up their beautiful land in favor of European occupation. So Ngidi’s uncle had to leave his place on the Manzimpofu Spruit. It was on these beautiful meadows that one day Ngidi had seen the Trappist Fathers and Precious Blood Sisters passing to their newly founded Centocow Mission on the south side of the Umzimkulu River. He had a chance to speak to the kind-hearted missionaries and was deeply impressed by their kindness even towards African herd-boys. His soul lingered often to ruminate on these loving missionaries for many years after. [3] The positive interaction that Ngidi experienced with the missionaries made him determined to learn more about them and to be educated by them.

In 1890, some Zulu people were moved from Umzimkulu Valley to Camperdown and the Emahlathini District in Zululand. This was because Chief Mqundane of the Mlaba, or Ximba, clan had taken part in the Zulu war of 1879, and his people were to claim their share of the spoils of war in Zululand. However, Ngidi’s uncle, who had taken part in the war against the British armed forces in Zululand, rebelled against Chief Mqundane and did not follow him, but remained defiantly near Camperdown. He named his daughter Nomambuka, meaning “the daughter of rebellion,” thus openly cutting off all ties and allegiance to his chief.

Ngidi’s mother left with Chief Mqundane and her younger son. Ngidi was left with his uncle, Nkotheni, near Camperdown. His uncle later moved to Nsikhuzane Stream, and Ngidi moved with him to the farm district between Richmond and Thornville Junction railway station. He helped his uncle, herding cattle and goats and ploughing the fields. Like his father, he enjoyed traveling, and he went to visit his mother and brother at Ekuphindeleni, near Pietermaritzburg. From there he had visited Maritzburg as a carrier of medicine bags for Nyawane, Mqundane’s brother, a renowned medicine man, who also had divining bones which his young carrier used to mix, shake, and throw on the floor to divine all events, happenings, and diseases to be cured by the physician and his master. Naturally, Ngidi, whose father was also a great inyanga (traditional healer), was right in his element. [4] During these visits to Pietermaritzburg Ngidi attended evening school where he learned Wesleyan prayers from the schoolmaster, who was also the local Wesleyan preacher.

Later, Ngidi returned to his uncle’s kraal; his uncle was at this time working for Indians for a wage of five shillings a month. As Ngidi received scant food and was made to work hard at his uncle’s kraal, he decided to run away and look for a job that would provide better remuneration. Near Thornville railway junction, he came across a man called Gong, whose European overseer, Mr. Williams, was looking for a young boy to babysit. In those days it was not easy for girls to babysit European children. Ngidi got the job and stayed with the family for eight months. The family moved from farm to farm and sometimes even went to Maritzburg. This “offered [Ngidi] an occasion to attend night school in the city. He was very eager to learn reading and writing.” [5]

At the age of eleven, the urge to become a Christian increased. At this time, Ngidi had worked for Mr. Williams for eight months and he was paid seven shillings per month. It was the custom in those days that if you wanted to terminate your employment, you simply asked your master to increase your pay. One day he saw an ox-wagon passing on its way to Umzimkulu and, wanting to use it as a means to reach Centocow, Ngidi asked for a pay raise. Mr. Williams set him free. Ngidi travelled with a middle-aged woman who had relatives in Richmond. When they reached Inondi store, the owner recognized him and wanted to hire him as a cook. As Ngidi knew that Centocow was nearby, he consented. In the space of a month, he saw all his old friends and prepared to start school and abandon his job as a cook.

His Schooling

So it came about that Ngidi was admitted to the mission boarding school at the beginning of October 1892. He offered himself for the baptism classes, and two years later, on March 19, 1894, he was baptized, choosing the name of Andreas. From then onwards he decided to live “a good life.” As he said himself, things became easier for him. “Even learning seemed easy after baptism as if the waters of salvation had washed even the brain in the black head of the African boy.” [6] Bede Gramsch arrived from Lourdes and took charge of the boarding house. He saw that Ngidi was very clever and believed he had the potential to become a priest. “Andrew Ngidi who has never attached any love for any place or familiarity with home surrounding agreed on the moment to try his best in following this ideal.” [7] In 1896, three more boys came forward to offer themselves for training for the priesthood. This resulted in letters being sent to Rome to apply for permission to train the four boys. Andreas Ngidi’s lifestyle offers us some perspective on the early Kholwa (or converts). [8]

The Kholwa fell into three categories: those who converted for future material gain, those who were pushed out of their homes by family and turbulent events and therefore needed land, and those who were outcasts. To some extent, the circumstances of Ngidi’s life-including his abandonment by his father and being left with an uncaring uncle by his mother-meant he could be included in the both the first and second category. For him this was an opportunity, possibly one which offered material gain. In addition, Ngidi wanted to become a Christian and acquire an education.

During the Griqua rebellion, which broke out near Kokstad, Ngidi was sent by Bede Gramsch to the Lourdes Mission with letters stating that the Lourdes school children should be sent to Centocow. In 1897, the rinderpest, a deadly cattle sickness, broke out, and then swarms of locusts devastated the mission lands and fields. [9] At times school children were asked to drive away the swarms. Ngidi used to go out with the superior of Centocow to pray and to spray disinfectant on the cattle in the fields. Meanwhile, the application letters which had been sent to Rome for the four boys to be trained as priests came back. Although they were all accepted, two of the boys then withdrew; this left Ngidi and Julius Mbhele as the only candidates for the priesthood.

A particular incident that encouraged Ngidi’s vocation as a priest is related as follows:

In the meantime, in 1898 the first African South African priest, Dr. Edward Mueller, had arrived in Durban and visited some of the mission stations and in Centocow Andrew saw him celebrating Holy Mass and he served mass. All that went to confirm his vocation and gave him more courage. If this African went to Rome and came back as a priest, why not I? Of all the Mariannhill Mission stations only Lourdes in Griqualand East answered the call and Julius Mkomazi-our Rev. Dr. Julius Mbhele-became available to go with Ngidi overseas. [10]

Ngidi was in grade eight at this time and, as the time to leave for overseas drew closer, he worked hard and reviewed his Latin lessons. He also practiced his English with the colored students from Kokstad.

His Departure for Rome

Andreas Ngidi and Julius Mbhele left for Rome on September 22, 1899, just two days before the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War. They stayed there for eight years and were quite successful. Ngidi says of his academic prowess, “In fact, the younger African passed these examinations with greatest honors, getting ‘Excellent’ in the Classics, Latin, and Greek, having always topped his classes in all subjects. A rare fact! Of course, Greek students could not be beaten in their own Greek language.” [11]

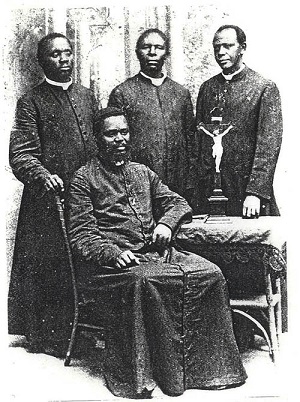

Ngidi and Mbhele both received doctorates in philosophy and, in addition, Ngidi completed a doctorate in theology. Soon, the fulfilment of their most ardent desire arrived: the day of their ordination to the priesthood in the Lateran Basilica by Cardinal Respighi, the vicar of Rome, on May 25, 1907. Both said their first masses the next day, “the Rev. Julius Mbhele, being the dean of the class, in the chapel of the Propaganda College; while Father Andrew Ngidi chose to celebrate his first mass in the German national church, Del Anima, for he had great love and gratitude for the German missionaries in his country…. Shortly before, their group had been received by the Holy Father Pope Pius X.” [12]

Before returning to South Africa, they visited Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and England, arriving home in 1907. [13] After their return, the two priests were assigned to different missions in the vicariate of Natal. Ngidi worked at Keilands, Lourdes, and Cassino Mission Stations. [14]

While working at Maria Telgte Mission, Ngidi experienced some trouble with his rector, Albert Schwieger. The rector spied on him, sneaking into Ngidi’s room and stealing the material he was writing, to see whether it was contrary to the missionaries’ beliefs. Ngidi had written some notes on what he thought the situation could be after the white man was defeated. After reading these the rector was scandalized. Ngidi wrote to the bishops about his grievances concerning the rector, saying:

If the Rev. Gentleman with whom I am at issue has made all the experiences I have made here in South Africa, the land of my birth and my all, he would not so easily take scandal at what I have written, or so lightly judge me as lost and the like. Has the said Rev. Gentleman once been showed the kitchen for a room for the night and for meals; has he even been obliged to sleep a sleepless night in a cow-stable at a farmer’s house? Has he ever been asked to take meals in the kitchen by a Catholic family; has he ever been in company with a European minister, shown a native teacher’s hut by the Protestant minister and so parted company with his fellow ministers? Has he been abandoned, in the train compartment, with the remark, “We don’t travel with niggers,” by a number of ministers of the same Catholic church; has he ever been asked by a superior of his to go and baptize a European child at a “farm” and there left as a boy to be asked by a native girl to come and eat in the kitchen (which, of course I refused, as I did in all other cases)? [15]

Ngidi later moved to Zululand and worked at Nongoma, Eshowe, Emoyeni Holy Cross Mission, Nquthu, Qudeni, and Nkandla. [16]

Missions

Ngidi was very ardent in preaching the gospel to the people. On several instances he was called upon to lead evangelism campaigns for the people. [17] This can be seen clearly in a letter from Bishop Jules Cenez OMI, vicar apostolic of Basutoland, “I have just found your letter today….With pleasure I give you faculties to come to visit tese [sic] poor souls in Basutoland, to hear their confessions, to baptize teir [sic] children and to teach them. I shall always be grateful for all the good you will do to them and for the help you will thus give us. I have been desirous for a long time to send something there.” [18]

Apparently, the vicar was experiencing some manpower problems in his diocese so he called upon Ngidi to help him. Andreas Ngidi and Thomas Pierce [19], both diocesan priests, were planning to form a religious order [20] specifically for missions [21] to non-Catholics. On the point of non-Catholics, Pierce thought that “the mission to non-Catholics is the surest, and often the only means of reclaiming bad Catholics.” [22] Ngidi was very enthusiastic in giving missions, as Pierce confirms: “It gave me great pleasure to hear that you have been giving missions again, this time in eswatini. And it is a most encouraging thing to find that your services are in demand over a large territory in the country.” [23]

Ngidi wanted as many people as possible to be converted. He was particularly impressed with the work of Bishop Spreiter of Eshowe. By 1926, Ngidi had left the diocese of Mariannhill and joined the Zululand vicariate. He worked in the diocese for several years and enjoyed considerable success, so much so that in 1937 Ngidi wrote to the bishop about the great success this diocese was enjoying:

I deem it will console and encourage your Lordship to hear the appreciation of the achievement of the Benedictine Order, under your Lordship’s wise and able guidance, for one who for eleven years has himself, though quite unworthy, been associated with the same Christian endeavor. From the year 1922 to the present 1937, the progress of the Eshowe Vicariate has with leaps and bounds overtaken and surpassed older missionary bodies in the mission field, both Catholic and Protestant. One hears now from one end of Zululand to the other that Catholic or Benedictine missions are springing up like mushrooms all over the land, and it is indeed true: Inkamana, Entabeni, Mbongolwane, Cassino, Gonzaga, Nongoma, and Fatima with their numerous outstations. Schools are really record breaking in the annals of missionary activity. [24]

When the four black priests were ordained, the Catholic Church and other churches did not have a strong missionary spirit-and, in fact, the Mariannhill and Eshowe dioceses were exceptions. These two dioceses were therefore aligning themselves according to the main focuses of the church: to evangelize people and spread the gospel as far as possible. This same missionary spirit is clearly evident in Ngidi. He went further by trying to join Thomas Pierce who wanted to form a religious order mainly dedicated to mission work. In spite of his successes, however, there were still some problems, especially with his bishop.

In this case we see a challenge to the hierarchy of the church: even though other people liked Ngidi to present missions, the bishop saw this as a threat to his authority and, in October 1933, he refused to give him permission to do so. Ngidi was invited by Father Muldoon OMI to preach a mission to the native teachers, catechists, and Catholics in general in Johannesburg. However, Bishop Thomas Spreiter refused to let him go. Among the reasons he gave was that, “Father Andreas is now on a new mission and engaged with a lot of work.” [25] But more pertinent is the reply he gave to the priest-in-charge, Muldoon:

In my opinion it would be a blessing to have…missions…to native teachers…But the case is, to have priests for such a work. Father Andreas Ngidi, some years ago, has given so far as I can remember, a mission in Pietersburg. The trouble was-that is quite privately-the result may perhaps been good for the audience-but not for himself. Therefore I stopped it to send him outside. Could I help on, I would do it with the greatest pleasure. I have here another native priest, Father Julius Mbhele. The case is the same and besides that he has absolutely no voice. Therefore, please excuse me. [26]

From the above letter the suggested conclusions are that the bishop wanted to stop Ngidi from preaching these missions because he thought that Ngidi would take too much pride from his pastoral success. The bishop went further and alleged that the results for both Ngidi and Mbhele were not good for them. To prevent Ngidi from becoming independent and successful, he forbade him to preach missions. There might be other reasons which caused the bishop to refuse, but the second letter is indicative of the attitudes that existed. When Ngidi preached the missions he became a threat, possibly to the bishop, and took much pride in his success.

The Catholic African Union (CAU)

Ngidi also worked with the Catholic Africa Union, which empowered black people through self-help projects so that they could be self-reliant. He asked people to be involved in projects which were going to help the priests and the people. For example, a person (not identified in the letter) wrote to him saying: “Father, I am contemplating about the task you have loaded upon me. I mean that of starting an ‘Association for Mass Stipend.’” [27]

The association was supposed to consist of ten men each contributing not less than £6-0-0 (equivalent to $778). To enhance this project, a newspaper was supposed to be started; the editor was to be Mndaweni. M. R. R. Dhlomo, editor of the Bantu World, was supposed to assist with journalistic skills. [28]

The Catholic African Union (CAU) was started by Bernard Huss, a priest from Mariannhill, who was very concerned about the betterment of Catholics. As Stuart Bate states:

The vision of the Trappists…was to establish Christian rural settlements around the mission where the local people were attracted to the Christian lifestyle through the advantages it offered: “better homes, better fields, better hearts” was the way this vision was articulated by Father Bernard Huss. Often this vision was linked with the idea of eventually providing the tenant farmers with some kind of freehold, something which was to be continually thwarted by the political authorities. Sometimes farms were acquired just for the sake of providing tenant farmers with land to work or even with the aim of giving them freehold in the hope that being close to the mission they would use the mission facilities of worship and education. [29]

The formation of the CAU was influenced by the founding of the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) in 1919. It is usually suggested that the Catholic organization was formed in response to the ICU or to protect the Catholic faith because the ICU was aligned with communism. [30] The ICU was involved in the mobilization of the largely illiterate and politically unsophisticated African rural people and was led by Clement Kadalie, a young Nyasalander. The main thrust of the ICU was to fight for the rights of the workers so that they were given a better deal. The CAU offered itself as an alternative. It wanted to improve the lives of the people because, by the early 1920s, drought, cattle fever, and crop failure had led to rampant poverty in the already overcrowded reserves. [31] It was more than a response to communism, as was pointed out by Lydia Broukaert, in her honors thesis “Better Homes, Better Fields, Better Hearts: The Catholic African Union, 1927-1939.” She argues that, even though the leaders of the ICU professed to be anti-Christian and antimissionary and the upheavals in Natal were quickly blamed on them, the church’s response in creating the CAU was an inherent cognition of the real grievances of Africans in the countryside of Natal and the changes that took place. The organization captured the support of the African Catholics who worked on the land of mission stations and of mainly Catholic teachers, who were born and educated at Catholic missions. [32]

The CAU meetings dealt with saving, cooperatives, farming, elementary bookkeeping, accounting, and business methods. From such meetings emerged practical organizations like the Farmers’ Unions, Savings Banks, and Thrift Associations. Every year, industrial and agricultural shows were held that provided important incentives for better home industries and farming practices. In 1926, the People’s Bank was founded in Transkei, followed by the establishment of branches elsewhere. Among these was the Mariannhill branch, which operated until 1979. [34]

The CAU promoted the Catholic social principles promulgated by Pope Leo XIII and Pope Pius XI. [35] In keeping up the spirit of CAU, Ngidi was heavily involved in training Africans for leadership positions and also in helping Africans uplift themselves economically. [36] A nondenominational savings scheme organization, which involved other churches, was formed and run by the CAU. Ngidi was asked to be an honorary advisor to the board of directors of this scheme.

When Ngidi joined the Zululand Diocese he became widely known, resulting in people often coming to him for advice and input. As Bishop Dominic Khumalo noted, “he was a well read man.” [37] An example of his popularity and counsel is the 1944 meeting of the Catholics Teachers Federation in Zululand, [38] at which B. W. Vilakazi asked Ngidi to give a talk on “The place of Catholic teachers in South Africa.” [39]

That Ngidi was an active participant in political and social reforms is reflected in his trying to establish an association for mass stipends, helping train Africans for leadership positions within the CAU, and giving advice to people in leadership positions.

The Zulu Cultural Society

Ngidi was fluent, and sometimes referred to as an expert, in Zulu. For example, in 1939, the publisher Shuter and Shooter wrote to him saying that his name had been forwarded to them by a Mr. A. Kubone of the Government Native School at Howick. Apparently, they had “…difficulty in finding people who are sufficiently conversant with the Zulu language and, of course, the new orthography, to check manuscripts before they go to the printers.” [40]

Selly Ngcobo from Natal University College asked Ngidi about the Zulu tradition on issues pertaining to food. Ngcobo was doing research on what foods are allowed to be eaten in accordance with Zulu custom. Ngcobo wrote, “I should be very glad indeed if you could perhaps in a separate paper give me a fairly comprehensive report on taboos and prohibitions connected with food (among the Zulu [people]).” [41]

In addition to his expertise in terms of the Zulu language, Ngidi also had an extensive knowledge of Zulu traditions and culture. Once, a young priest named Dominic Khumalo asked Ngidi about some Zulu customs. He recalls that Ngidi was a short, jovial man. Khumalo asked him about the occasion in the Zulu marriage and about when it is considered official. Ngidi said, “The couple assemble…the elders ask them, ‘Do you want to be married?’ And the couple say, ‘Yes.’…… Later, the government put police officers, and they would ask the couple whether they wanted to get married. If they said yes, then there was another big dance which demonstrated that the marriage was now official.” Khumalo further inquired, “Suppose the second part was not performed, after the whole day of feasting, will the marriage be valid or not?” Ngidi replied, “It [marriage] will not be there.” [42]

Ngidi did some translating of the Bible and also of the mass book into Zulu. [43] He also published articles on Zulu orthography. Here is an excerpt of a letter Ngidi received: “I got a letter from Rev. M. Kalus for publication in UmAfrika in which he criticizes your articles on orthography. Probably he has sent you also a copy of it. I hope you will not be influenced by his letter, but will finish your articles which are very interesting.” [44]

Ngidi was involved in the Zulu Cultural Society (Ibandla likaZulu) which had been formed by the Natal Bantu Teachers Union (NBTU), later changed to the Natal Teachers Union (NATU), and then given complete autonomy. Its aims were to encourage the African in his worthwhile indigenous culture, to stimulate intelligent research on the blending of cultures, and to tell the world who an African was. [45]

The society had 200 members including all the chiefs in Natal and Zululand. It consisted of an executive committee and committees on religion, music, economics, Zulu history, Zulu orthography, and the Natal Code of Native laws. Ngidi served on some of these committees with B. W. Vilakazi from Witwatersrand University. [46] While deeply involved in this society, he also helped other members. For example, Chas Mpanza, a member of the society, once asked him to help with the “Zulu place-names.” [47] No one else in the country could assist, as Mpanza explained, “You will understand, Father, that I would not have thought of giving you all this worry if I could find someone else in the country who could give me dependable guidance in this matter.” [48]

The South African government also consulted him when it was preparing a collection of native history and customs. [49] The “natives” were going to be paid for writing down this history. A person was supposed to write a detailed history of a tribe, stories of individual people, customs, and praises. The emphasis was that, “the (quarter) information should be obtained only from an old or reliable person and their exact words should be written.” [50] All these requests suggest that people relied on Ngidi and also that he must have been a knowledgeable person. History, however, does not seem to acknowledge this aspect of Ngidi’s life.

From Ngidi’s writings and his involvement in the Zulu Cultural Society, one can suggest that Ngidi was trying to uncover and affirm Zulu culture by contesting the European worldview. Instead of embracing new European cultural elements, he went back to his own culture to find his identity. In this way, he contested the whole process of colonization and civilization, which looked at most of black culture as “barbaric.” This might not have been a conscious challenge although, as we shall see later, he complained to the abbot, saying, “If I am not free to commit to writing subject matter for my private study, consideration, reasoning, and also speculation, I fail to understand why I should be allowed to think at all.” [51]

His Purchase of Land

In 1910, after the declaration of the Union of South Africa, a committee was selected in Parliament to formulate legislation which would restrict land ownership by Africans and limit the number of Africans who could squat on white-owned land.

With the introduction of the Land Act of 1913 and the amended Act of 1936, both African and European missionaries faced problems with the issue of land. The racial lines used to divide the country meant that Europeans could not buy land in black areas and vice versa. Even though Bishop Fleischer objected to diocesan priests owning land, [52] Ngidi went ahead and bought two plots in Clermont Native Township outside Durban. [53] Some priests used land fruitfully to the advantage of the Catholic Church:

Father Edward Mnganga has not been questioned about his plot at Waschbank. He has been allowed to build a chapel and school there. This is stated in a letter to Father Leyendecker from Andreas Ngidi who was at the Benedictine Mission at Nongoma in Zululand in 1936. See also the Title Deed for Plot 637 and 628, the Clermont Township (Proprietary), Ltd., Cassino, Nqutu via Dundee, August 15, 1924. [54]

Ngidi himself clearly recognized that owning land was an advantage. “In fact, the fathers here [in Zululand] would only be too glad to have native priests buy land where European missionaries are debarred and where schools and chapels could be obtained in accessible regions to Europeans.” [55] Indeed, Ngidi used this advantage to the fullest and purchased land. Some other priests used the opportunity to earn a living, too. For example, Fr. Julius Mbhele bought a farm near Ixopo. Since the priests were not very sure of their future, especially in the Mariannhill Diocese, buying property was sometimes used as a safety device for times of trouble.

Fundraising for Scholarships

Ngidi helped as many people as he could with education. Since he was influenced by Bernard Huss’s philosophy of Catholic upliftment, he carried his responsibility with great commitment. He raised money for people like R. A. Mndaweni [56] and Emmanuel H. A. Made to complete their tertiary education. Some of his friends, like B. W. Vilakazi from Witwatersrand and E. P. Mart Zulu from Johannesburg, also helped out. When Bishop Spreiter died in 1944, Vilakazi and Made-both former students of Inkamana High School-set up a scholarship at the school which was for matric students only. [57] Inkamana High School was the first in the country to have students completing the University Joint Matriculation Board Syllabus. Bishop Khumalo concluded by stating, “I hear afterwards that he helped many people. That is one of the reasons why he had properties and he didn’t have much of a salary from the bishops. Today they may but strictly speaking the priest hasn’t got a salary. He gets something to help him live. But I heard that Father Ngidi was very interested in the education of young people.” [58]

It is clear that, by the late 1940s, Ngidi had done a great deal for the church and his achievements as one of the first black priests were well known. During these last few years of his life he met Dominic Khumalo, Mansuet Biyase, and Nicholas Lamla. These bishops and this priest have provided some valuable insights into his life through interviews. By 1945, Ngidi’s health had started to deteriorate; he had developed diabetes and stayed in hospital at Nongoma for almost six months. He died in 1951 and is buried in the cemetery at Inkamana.

George Sombe Mukuka

Notes:

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.” Full text in the appendix below.

-

Idem.

-

Idem.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1 no. 2, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Idem.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1 no. 5, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Norman Etherington, “Christianity and African Society in Nineteenth Century Natal,” in Natal and Zululand from Earliest Times to 1910: A New History, eds. Andrew Duminy and Bill Guest, (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1989), 294-295; see also, Norman Etherington, “The Rise of the Kholwa in South-East Africa: African Christian Communities in Natal, Pondoland and Zululand, 1835-1880,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University, 1971).

-

For a full discussion on the epizootia of rinderpest, see Benedict Carton, “Blood from your Sons: African Generational Conflict in Natal and Zululand, South Africa, 1880-1910,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University, 1996), 153-161.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1 no. 8, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1 no. 9, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

The autobiography ends with their arrival in South Africa. The other information on where they worked and what transpired is from oral interviews and archival material; see also, “Ein freudiges Ereignis,” Vergissmeinnicht 63, (1907), 194.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.”

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Andreas Ngidi, Letter to the Abbot,” Telgte, April 30, 1917.

-

UmAfrika, August 18, 1951.

-

The Catholic Church defines its mission as spreading the message of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments, and exercising charity.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Father J. Cenez, Letter to Ngidi,” Roma, November 13, 1911.

-

Father Thomas Pierce was a diocesan priest who wanted to form a congregation for missions. He was backed financially in the United States of America by Monsignor A. E. Smith of Baltimore. He needed four other priests to commence his congregation.

-

See Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter of Father Pierce to Father Ngidi,” Hartebeestpoort Hotel Schoemansville, via Pretoria, September 16, 1930. The letter outlines the details of the congregation and is discussed by the delegate, Bishop O’Leary, and Father Pierce.

-

See The South African Apostolate, Hartebeestpoort Hotel, Schoemansvill, via Pretoria, January 1932 (pamphlet also acknowledged by Bishop O’Leary).

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter from Pierce to Ngidi,” Pretoria, June 19, 1931. Between 1931 and 1934, Father Pierce had preached 29 missions. See also, Southern Cross, January 23, 1935.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter from Pierce to Ngidi,” Pretoria, September 4, 1931.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Copy of Letter to the Bishop from A. H. Ngidi,” The Eshowe Catholic Mission, December 19, 1937.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter to the Native Teachers Council, Johannesburg from Bishop Spreiter,” October 12, 1933.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter from Bishop Spreiter,” October 12, 1933.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter to Ngidi from R. Vilakazi,” November 20, 1932.

-

Idem.

-

See Stuart C. Bate, “Points of Contradiction: Money, the Catholic Church and Settler Culture in Southern Africa: 1837-1920. Part 2: The Role of Religious Institutes,” Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 26, no. 1 (2000): 165-188.

-

Joy B. Brain, The Catholic Church in the Transvaal (Johannesburg: Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, 1991), 207.

-

Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story (Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association, 1992), 320.

-

Lydia Brouckaert, “Better Homes, Better Fields, Better Hearts: the Catholic African Union, 1927-1939,” (B.A. Hons Thesis, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, 1985), 12-13. Mariannhill Monastery Archives.

-

Brouckaert, “Better Homes, Better Fields, Better Hearts,” 40; see also Aldegisa Mary Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill in the Province of Mariannhill, South Africa (Mariannhill: Mariannhyill Mission Press, 1984), 56.

-

Brouckaert, “Better Homes, Better Fields, Better Hearts,” 40-64.

-

Hermann, History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill, 57.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter to Ngidi from Malinga,” Waterfall Road, Mayville, Durban, August 29, 1939; see also, UmAfrika, June 28, 1947.

-

Dominic Khumalo, interview by author, March 25, 1997, Pietermaritzburg, tape recording.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “B. W. Vilakazi, Letter to Ngidi,” Wits University, Johannesburg, February 3, 1944.

-

Benedict Wallet Bambatha Vilakazi (also referred to as B. W. Vilakazi) was a poet, novelist, scholar, and teacher. In the 1930s he attempted to write Zulu poetry in using prosody and rhyme derived from English verse forms. For a full discussion see, David Attwell, “The Experimental Turn in Black South African Fiction” in South Africa in the Global Imaginary, eds. Leon de Kock, Louise Bethlehem, and Sonja Laden, (Pretoria: UNISA, 2004), 158-159.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Shuter and Shooter Book and Stationary, Letter to Ngidi,” June 13, 1939.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Selly Ngcobo to Ngidi,” Natal University College, Warwick Avenue, Durban.

-

Khumalo. interview.

-

Idem.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “A letter from J. B. Sauter RMM to Ngidi,” Mariannhill, Natal, November 21, 1930.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter to the Editor: Reply of the Zulu Cultural Society (Signed ‘Confidential for Father Ngidi’),” n.d.

-

Idem.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “A Letter from Chas. J. Mpanza to Father Ngidi,” Pietermaritzburg, Natal, November 7, 1939.

-

Idem.

-

See Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter entitled, ‘Collection of the Native History and Customs’,” July 20, 1938.

-

Idem.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Ngidi, Letter to Abbot,” Telgte, Franklin, April 20, 1917.

-

See Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #1, “Letter to Ngidi from Leyendecker,” March 18, 1836.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter to Father Leyendecker from Ngidi,” Benedictine Mission Nongoma, Zululand, April 14, 1936; see also, Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Title Deed for Plot 637/628, The Clermont Township (Proprietary), Ltd,” Cassino, Nqutu via Dundee, August 15, 1924.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2 no. 3, “Letter to Father Leyendecker from Ngidi,” Benedictine Mission Nongoma, Zululand, April 14, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2 no. 7, “Letter to Father Leyendecker from Ngidi,” Benedictine Mission Nongoma, Zululand, April 14, 1936.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “Letter from Mndaweni to Ngidi,” Inchanga High School, February 11, 1949.

-

Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid, Andreas Ngidi: File #2, “A Letter to the Public,” (signed by Mart Zulu and B. W. Vilakazi), Johannesburg, April 3, 1944.

-

Khumalo interview.

Bibliography

Attwell, David. “The Experimental Turn in Black South African Fiction,” in South Africa in the Global Imaginary, eds. Leon de Kock, Louise Bethlehem and Sonja Laden. Pretoria: UNISA, 2004.

Bate, Stuart C. “Points of Contradiction: Money, the Catholic Church and Settler Culture in Southern Africa: 1837-1920. Part 2: The Role of Religious Institutes,” Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 26, no. 1 (2000), 165-188.

Brain, Joy B. The Catholic Church in the Transvaal. Johannesburg: Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, 1991.

Brouckaert, Lydia. “Better Homes, Better Fields, Better Hearts: the Catholic African Union, 1927-1939.” B.A. honors thesis, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, 1985.

Carton, Benedict. “Blood from your Sons: African Generational Conflict in Natal and Zululand, South Africa, 1880-1910.” Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1996.

Etherington, Norman. “Christianity and African Society in Nineteenth Century Natal” in Natal and Zululand from Earliest Times to 1910: A New History. Edited by Andrew Duminy and Bill Guest. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1989.

——–. “The Rise of the Kholwa in South-East Africa: African Christian Communities in Natal, Pondoland and Zululand, 1835-1880.” Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1971.

Hermann, Aldegisa Mary. History of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Mariannhill in the Province of Mariannhill, South Africa, Mariannhill: Mariannhill Mission Press, 1984.

Khumalo, Dominic. Interview by George Mukuka, March 25, 1998, Pietermaritzburg. Tape recording.

Ngidi, Andreas: File #1-7, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Andreas Ngidi.” Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid. See Addendum for full text.

Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story. Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association, 1992.

South African Apostolate, The. Hartebeestpoort Hotel, Schoemansvill, via Pretoria, January 1932.

UmAfrika, August 18, 1951.

This article, received in 2008, was written by Dr. George Sombe Mukuka, a faculty research manager at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and 2008-2009 DACB Project Luke Fellow.

Appendix: Autobiography of Mdontswa Andreas Ngidi

Chapter I - Mdontswa’s Birth

Mdontswa Ngidi was born in the year 1881, after the Zulu War of 1879, just after the capture of King Cetshwayo, of Impande and of Senzagakhona, younger brother to Shaka and Dingana.

Mdontswa’s father, Mbhemiwegudu Ngidi, the son of Mabuyabuya, the son of Ghashana, the son of Buhlazo, had three wives. Two of these wives were of the Emagwabeni clan. Mdontswa’s mother was the third wife; her name was Nomakholwa Ndlovu. The first two wives had several sons and daughters: Ndleleni, Gugile, Nomasomi, Noyinyoni, Majuba, Mlandwa, Somsewu, and Nomcebo, the last two being of the second wife, Mantandela. Mdontswa’s mother had only two sons, Mdontswa and Mbhelekwana, because their father took them to live with their mother’s brother on Mondi Mountain, Cekwane or Dronkvlei, when he left his kraal for good to go to Pondoland to become a wandering doctor of medicines. Before that Mdontswa’s father drove an ox-wagon from Durban to Johannesburg. It is said that he was so strong, that when going down Donlsamfana Mountain (near Inchanga Railway Station)–if ever he found it impossible to stop the wagon–he would take off the rear wheel with one hand, and get the team down safely. Also it is said that once some German settlers near Botha’s Hill got into trouble with him, their oxen having trespassed on his mealie (corn) fields. When Mbhemi went out single-handed to fight old Mabuyabuya, Mbhemi’s father, had to call his other sons to hold their brother back so as not to cause more damage and bloodshed.

Mdontswa and his siblings each had a story behind their name. Ndleleni’s name comes from the word endleleni because he was born when his father was still on the way to his birth. Gugile was born at a time when her father had been away so long that her mother thought she might become old before he returned from his wanderings. Nomasomi was born while he was away with the Somi Clan. Noyinyoni was born when the old woman had trouble with birds in her field. For Mlandwa’s birth he had to be fetched. Majuba was born while their father was serving in the Majuba War between the British and the Boers. Somsewu was named after Sir Theophilus Shepstone who subdued the Zulus in 1879 under Cetshwayo. Mdontswa’s parents intended to name him Mbhelekwana after his older brother who died during childhood. However because of events during his birth he was named Mdontswa, which means “extracted” instead. Nonnatus and his younger brother took the name Mbhelekwana in his place.

Having given Mdontswa’s early background and situating him within his historical moment in the wider history of South Africa, we shall proceed with his story alone.

All the descendants of Mabuyabuya, the father of Mbhemi, and the grandfather of Mdontswa, were about 600 or 700 children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. As a result of strained family relationships and circumstances, Mbhemi thought it good to bring his third wife, Nomakholwa Nandlovu to the Denge Plateau, near Alverstone Railway Station, some three miles towards Cato Ridge, with her two sons, Mdontswa and Mbhelekwana. Even here the two families did not live together in perfect peace. Nomasosha, a daughter of Nyokana Ngidi, Mbhemi’s brother, with whom he had recently come to dwell, hurt Mdontswa, her older cousin, on the forehead with an Indian clay-pipe; the mark on Mdontswa’s face is still visible. Nomasosha’s name indicates that she was born a year before, when the British soldiers were arriving for the 1879 invasion of Zululand under Theophilus Shepstone.

Around 1886 Mdontswa’s father decided to renew his wandering habits. He took Mandlovu with her two children from his Denge kraal to Drinkvlei between the Inkonzo and Umzimkhulu Rivers, under Mondi Mountain, on the main road from Durban to Kokstadt in Griqualand East, Cape Colony. The Inkonzo River flows from the east of Ehlabeni forest and just below the Amabedlane mountains in Natal; the Umzimkhulu River flows from the Drakensberg between the Pholela and Umsivubu Rivers in Griqualand.

Having done so he immediately left Natal for Pondoland where he sold medicines for many years. Thus Mdontswa’s mother, Nandlovu, had to stay with her people near Mondi Store at Manzomphofu. Eventually the two boys grew big enough to help their uncle, Nkotheni ka Cimbi Ndlovu, to look after his cattle, horses and goats along the slopes of Mondi Mountain, near the present day railway station and township of Creighton.

Since 1886 Mdontswa’s uncle, Nkotheni, had lived under Chief Mqandane Mlaba, or Ximba, to whose chieftainship belonged the whole of the Cekwane Valley. But now the time was coming when the Africans had to give up their beautiful land in favor of European occupation. Consequently, Mdontswa’s uncle had to leave his place on the Manzimpofu Spruit. It was in these beautiful meadows that one day Mdontswa saw the Trappist Fathers and Precious Blood Sisters passing to their newly founded Centocow Mission on the south side of the Umzimkhulu River. He had had a chance to speak to the kind-hearted missionaries and was deeply impressed by their kindness even towards African herd boys. For many years, his soul ruminated upon his encounter with those loving missionaries.

Now about the year 1890 the Great Trek began from Umzimkhulu Valley to Camperdown and even to Emahlathini District in Zululand. Chief Mqundane of the Mlaba, or Ximba, Clan had taken part in the Zulu War in 1879 and his people were to have their share in the spoils of war in Zululand. Mdontswa’s uncle, who had taken part in that war of the invasion of Zululand by the British armed forces now rebelled against Chief Mqundane and did not follow him, either to his Ndondakusuka Kraal, nor to Zululand, but remained defiantly near Camperdown, and named his tenth born daughter “Nomambuka” (the daughter of rebellion), thus openly cutting off all relations and allegiance with his chief.

Mdontswa’s mother went with the Ekuphindeleni group of the Cekwane Mlaba Clan, thus separating herself from her brother Nkotheni for good. She took her younger son Mblelekwane with her, while Mdontswa remained with his uncle near Camperdown for some time. When later Nkotheni moved to Nsikhuzane Stream his nephew continued to live with him in the farm districts between Richmond and Thornville Junction Railway Station. As the time passed the boy grew stronger and stronger, herding cattle and goats and plowing for his uncle. He also visited Ekuphindeleni in order to see his mother and brother. From there he visited Maritzburg as carrier of the medicine bags of Nyawane, Chief Mqundane’s brother, a renowned medicine man. Nyawane also had divining bones which his young carrier Mdontswa used to meddle, shake, and throw on the floor to divine all events, happenings and diseases to be cured by his master the physician. Naturally Mdontswa, whose father was also a great inyanga (traditional doctor), was right in his element. He also began attending an evening school there and learned Wesleyan prayers, as the master was also the local Wesleyan preacher. Eventually the time came for Mdontswa to return to his uncle beyond the Umlazi River between Maritzburg and Richmond Township.

Having seen part of the world beyond his village, young Mdontswa did not continue to look after his uncle’s cattle and donkeys for very long. Unfortunately, one day he accidently burned his grandmother’s hut and all its contents, a mishap that did not go unpunished. His mother came to look for him and brought him some clothing, as he received only scanty food and plenty of work from his uncle. Meanwhile Mdontswa’s cousin was working with the Indians and got five shillings a month. The burning of the hut, subsequent punishment, and the work for nothing took a toll on the boy, notwithstanding his good will and hard working qualities.

One good day, after an undeserved beating, Mdontswa left his uncle and looked for some small remunerative job. Near Thornville Railway Junction he came across a road and met Gong, whose European overseer was looking for a boy to work as a babysitter. In those days it was not easy to get girls to take care of European babies. So Mdontswa was soon blessed with a job. For seven months he remained with his white master, traveling from farm to farm and sleeping alone or with other Africans in their tents while on the road. His master, Mr. Williams, was good and kind to the poor boy, and his wife was kindness itself. Sometimes visits to Maritzburg from the roadside offered Mdontswa an occasion to attend night schools in the city. He was very eager to learn how to read and write.

After working for Mr. Williams for eight months looking after the baby, Mdontswa remembered the good missionaries and missionary-sisters who had passed him when he was herding cattle near Mondi Store some years back. Now that he was eleven years old he thought about them and their Centocow Mission School and church, all of which his aunt, Nombango Ndlovu, had often spoken to him about. He often considered leaving his babysitting job and going to that Catholic mission to learn reading and writing and eventually to become a Christian, as some relatives of his had become, according to his aunt. Just about that time some wagons passed Richmond, heading for the Umzimkhulu Stores and the Cape Colony. Because his Uncle Nkotheni was a long time ox driver of old Mr. James Cole over the Ingwagwane River between Centocow and Lourdes Catholic Missions, Mdontswa saw the chance to get into one of the missions. As is common practice for African boys when they wish to leave European service, Mdontswa asked his good master to increase his pay. He had been getting seven shillings per month for seven months. But as even older boys than Mdontswa were getting only five shillings a month, Mr. Williams would not increase his pay. Mdontswa simply told his master that he intended to leave his service that very evening. And the white man gave the boy his wages and belongings and let him go into the darkness of the approaching night.

Fortunately, Mdontswa was hardly on the main road from Maritzburg to Mzimkhulu when he met a middle-aged woman going the same way. There was no need for any wagon. She had friends in the town of Richmond, and before nightfall the two travelers were under cover. They started early the next morning and crossed both the Umkhobeni and Umthomazi Rivers before noon. Before dark they were near Amabedlana Mountain. They passed the night at a friend’s kraal, as all kraals were friendly and hospitable in the good old days. The early sun saw these travelers on their way down the slopes of Mount Amabedlana. Crossing the Inkonzo River about noon, they reached Mondi Store in the late afternoon. Mr. Ming, the storekeeper, recognizing the boy Mdontswa, asked him to work for him as a cook for himself and his friend. The boy, knowing that Centocow was not far away consented, hoping first to see some friends from the mission. In a month’s time he saw all his old friends and prepared to leave cooking for schooling.

Chapter II - School and Education

On the first day of October 1892, Mdontswa was admitted to the Centocow Mission Boarding School, being a little more than eleven years old. The boy at once showed that he was very keen to learn and very diligent in his work. That was natural enough as the Ndlovus had been rather strict and rough with the boy from early childhood. The boy had nobody to take his side when too much was required from him. The school authorities, therefore, realizing that something could be done with the small boy, soon began to like him. But the boys of middle Natal, mostly Bhacas, did not like him, because he was a stranger to them. He was hated even more when the superiors showed signs of favor towards this young boy from the coastland, this Mzantsi, as the other boys called him. As it often happens in these circumstances, young Mdontswa had to suffer for all the kindness shown him by those in authority for his good behavior and diligence at work. In a big school with more than a hundred pupils it was not always possible to know who was wrong when quarrels and fights took place among the younger boys. Frequently Mdontswa was accused of causing these squabbles and fights. But seeing that he was blamed for the faults of others, he took the law into his own hands and fought the battles for himself and was often punished for having fought and won. This continued frequently until more sober and more careful bigger boys reported the matter to the proper authorities, drawing their attention to the fact that a strange boy would not start quarrels against the majority of his equals without serious provocation on their part.

At this stage Mdontswa was so careful and well behaved that he did not make himself liable to another punishment if he could help it. Thus constrained to keep order in all things he was attentive at school and soon surpassed everyone in his class. His favor and academic success only brought more jealousy from the other students. Yet, his only wrongdoing was fighting when attacked, and he always brought his attacker to book. Consequently, the other pupils began to refrain from attacking Mdontswa, and he was spared many a squabble and consequent caning. Owing to his hard work in the vegetable gardens with the Sisters, he was chosen to work in the fields during plowing time. When he came back to school he was still first in the class, as before. With this confidence in himself, Mdontswa continued in his studies day after day, all the while growing physically stronger and stronger.

Eventually he enrolled in the baptism class. During this time he carefully prepared himself to embrace Christianity, following his mother’s name, Nomakholwa, mother of Christ. When his two years of catechism were completed, the time for Mdontswa’s baptism drew near. The life-altering decision about whether or not to be baptized was left to him alone, as his father was still away in Pondoland and his mother at Ntweka, near Inkhambathini (Table Mountain), half way along the Umzumluzi and Umngeni Rivers from Maritzburg to Durban. The Centocow Mission at that time was still under the Rev. Fr. Gerard Wolpert OC, its founder, the Rev. Fr. Baldwin, and the Brothers and Sisters. Frater Innocent Büchner, Chrysogonus, and Cunibert were also there in charge of the Boys’ School, in succession.

On March 19, 1894, Mdontswa was baptized and chose the name of Andreas. Theodore Duma sponsored him as a godfather. Now that he was baptized, Andreas Ngidi resolved to lead a good Christian life, giving up all his fighting habits as much as he could, since all provocations, naturally revived the old and inveterate passions of his iron constitution. Even learning seemed easy after baptism, as if the waters of salvation had washed even the brain in the black head of the African boy. Andreas, ever eager to learn, was now enthusiastic for further educational advancement. As Frater Bede Gramsch arrived from Lourdes to take charge of the boys’ Boarding School, he soon detected rare talents and a high mental caliber in Andreas. He tested Andreas to see if he might have a priestly vocation. Andreas who had never grown attached to any place or had any familiarity with home surroundings, agreed in a moment to try his best to live a priestly life. Three other boys came forward with the same high purpose. This was about the year 1896 or a little before. Soon afterwards the Griqua rebellion broke out near Kokstadt. Andreas, having gained more in confidence, was sent alone to Lourdes with special letters requiring that the Lourdes school children be sent to Centocow. All those from the Lourdes Mission were to become refugees and a European Laager during the Griqua trouble. A notorious rider, Andreas was back in Centocow before sundown to the joy of all concerned.

This year and the following were years of misfortune. First came the rinderpest (cattle sickness) and then the locusts. In both crises Andreas’s superiors sought his help. Swarms of locusts devastated the mission lands and fields, so much so that and even schoolchildren were asked to help drive the swarms away. Andreas went out with Fr. Superior to pray for and sprinkle the cattle on the veld.

Now when the letters came back from Rome concerning priestly vocations, the three boys who had volunteered to go with Andreas retraced their steps and Andreas alone came forward. In the meantime, in 1898, the first African South African priest, Dr. Edward Mueller, arrived in Durban and visited some of the mission stations. In Centocow Andreas got to serve at a Mass in which Mueller celebrated. That experience helped confirm his vocation and gave him more courage. “If this African went to Rome and came back as a priest, why not I?” he reasoned. Of all the Mariannhill mission stations, the only other station where a pupil answered the priestly call was Lourdes, in Griqualand East. Thus Julius Mkhomazi-later the Rev. Dr. Julius Mbhele-accompanied Andreas overseas for priestly training.

At this time Andreas was doing his standard six. Some scholars had come to Centocow from the neighboring Catholic Mission of Reichenau in Bulwer District. The two missions were always friendly since both had been started by the Superior of Centocow, Fr. Wolpert. As the time for going overseas drew near, Andreas worked harder, revising his Latin lessons. Before sailing to Europe he had a good chance to speak and practice English with colored students from Kokstadt. He had almost abandoned African companionship and sought the companionship of the Slaughters and Uyses, so that he could become fluent in English. Toward the end of 1898, it became time to leave for Mariannhill.

Yet an important duty remained to be done. Early in 1898 Andreas had learned that his old father had come home from Pondoland. Andreas wanted to go home and ask permission to travel from his father, as the government would not issue his passport without his father’s permission since he was under eighteen years of age, a minor.

Therefore, early in 1898, Andreas left Centocow mission for the first time in seven years to go home to Botha’s Hill to ask his father for permission to go to Europe for his higher studies, that he might one day become a priest. Dr. Edward had become a priest and Andreas wanted to follow in his footsteps. In order to see his father, he had to go more than 100 miles on foot from Umzimkhulu to Botha’s Hill. After about three days he arrived home, and was hardly recognized by his own people who had not seen him since he left them with his father and mother sixteen years before when they went to stay at Denge near Cato Ridge railway station in Camperdown district.

The father recognized his son Mdontswa and asked after his mother and his younger brother. Andreas told his father that both were safe at a Catholic Mission Centocow, near Mondi Store, where he had left them in 1886. The father thanked his son for looking after his mother and his brother so well. Andrea informed his father that he had taken after him in desiring to go around round the world and introduced the subject of his visit. The old man listened quietly to the whole story and at the end replied that if he himself had given the bad example of roaming about the world as a doctor, he could not refuse permission for his son to get more education and become a great Roman Umfindisi, since his mother was already staying with Ama-Roma. Old Adam Mbhemi thus cheerfully allowed the first son of his third wife Namakholwa Ndlovu to travel abroad.

Andreas availed himself of the opportunity to visit Mariannhill, which is only fifteen miles from Botha’s Hill, his home. The sight of Mariannhill, the monastery, the convent, St. Francis College and St. Anne’s Girls’ School made a lasting impression on the seventeen-year-old Centocow scholar. Andreas went home to Botha’s Hill and prepared himself for the long way back to school. It was not pleasant to think of walking another 100 miles. Now that he had seen his old father, he was happy and pleased that he had permission to go overseas for his higher studies. The prospect of seeing the oceans and the land of the white people was very interesting. In a few days his visit drew to an end, and he longed to return to his books. Quite alone he started from Botha’s Hill to Dronk Vlei and Centocow Mission between the Umzimkhulu and Ingwagwane Rivers. He first passed Richmond and crossed the Illovo, Mkhombeni, and Umkhomazi River, already known to him from former journeys. He reached Centocow in two or three days and the young man soon felt at home again in the company of his dear books.

The fateful year of 1898 was quickly drawing to an end; 1899 was fast approaching and with it rumors of a Boer war. Since the abortive Jameson raid on the Transvaal and Orange Free State, all attempts to restore genuine peace between Great Britain and the South African Republics were useless and war had become inevitable. Young Ngidi was always a keen supporter of the Dutch Republicans, whose language his father spoke so fluently, as almost all ox wagon drivers did on the Durban-Johannesburg main road. Early in 1899 rumors of war became so frequent that even schoolchildren indulged in them with impunity. The bigger boys at school even took sides, some with the British and others with the Northern Republicans. They had been treacherously attacked by the British raiders and African sympathy even in Natal was with the Boers. Young Ngidi was known for his strong Republican tendencies. A good and eager reader of history he could not help holding to his father’s traditional and sympathetic feelings for the Dutch. But he had to break all connection with Southern African politics and leave for Italy.

His superiors urged him to leave quickly for Mariannhill as his ship, the Herzog of the German-East African line, intended leave Durban before the impending South African War. Having prepared everything, Ngidi left Centocow for Mariannhill. But one hitch remained: his father, Mbhemi Ngidi, had died during 1898, before the government granted Andreas’s passport. From Mariannhill he had to go to Botha’s Hill to see his oldest half-brother, Ndleleni Ngidi, about his passport. His brother testified at Umgeni Court, Maritzburg, that his father had consented to Andreas Ngidi going overseas for higher education, and he could not change his father’s disposition regarding his younger half-brother. The passport was granted and Ngidi returned to Mariannhill and peacefully continued his studies.

As Mariannhill was on the level of Centocow educationally, Ngidi also continued his standard six studies at Mariannhill. He was well situated there in regard to his knowledge and scholarship. As the days passed, he soon rose to the top of his class. Fr. Benno OC, a teaching theology student who was an American of French-German descent, helped Ngidi immensely in his further studies. During this time, Ngidi also met his colleague Julius Mbhele. The two have been friends ever since, a friendship of almost 50 years.

The day of departure for Europe was fixed. The two African students were to leave on September 22. Unbeknownst to them, this was two days before the outbreak of the war between Great Britain and the Dutch Republics. They embarked in Durban. The Herzog was full of refugees from the Transvaal and the Orange Free State and many who did not want to experience the horrors of war and the concentration camps. The Herzog set out in due time, and the African lads found themselves in the company of white men in the great war exodus from South Africa.

It was the first time that the African boys were on board a ship. The Herzog sailed safely into Delago Bay and into Lourenco Marques where more refugees from Johannesburg were taken on board, as the war had broken out in the Transvaal. People from all over South Africa who did not like the miseries of war boarded the ship. They were of British and Dutch nationalities, and many were political suspects who had expressed their opinion on the ensuing armed conflict or who had been known to favor one or the other side.

The Herzog was jam packed and soon left the harbor of Lourenco Marques for the high sea, as if afraid of being intercepted by British warships before reaching Europe. The African students worried about the possibility of the Herzog being captured and taken to England before they had a chance to disembark at Naples, their destination. Fortunately, the German ship passed the Suez Canal and entered the Mediterranean Sea without interference and safely reached Naples in the afternoon. The African students took a train and arrived in Rome the same evening. Once there, they used their few Italian words and a written address to reach the Trappist Monastery with an Irish-English speaking prior who received them for the night.

The next morning, after breakfast, the Trappists brought the African students to the Propaganda College, near Piazza di Spagna and presented them before the university college authorities and duly admitted them as students. The Africans could not converse with most of the Propagandists except those from the British Empire and the Americans, with whom they spoke English. Therefore the two Africans had nothing better to do than to immediately adjust to their new conditions and begin their studies in all earnest.

It was about the middle of October and the school was just opening after the summer holidays. Since the European winter was just beginning in the northern hemisphere, the South African students experienced an extraordinary second winter of 1899.

Chapter III: Rome for Eight Years in the Propaganda College, the International College of the Catholic Church

Now part of the work was done and our African boys were in Rome, the greatest “seat” of all education. For hundreds of years Italy, France, Spain, Germany, Hungary, and England had had colleges in Rome for the education of their national clergy in addition to their own national colleges in their respective kingdoms. But even those countries that did not have their colleges in Rome could send their candidates to the Propaganda College to be trained for the Catholic priesthood under the very eyes of the supreme pontiff, the father of all Christian nations in God, the vicar of Christ. It is here, then, that the two African students came for their higher education and courses in Latin, Greek and Hebrew, philosophy and sacred theology. There they accomplished all that was required of them to complete the whole course of studies in preparation for the holy priesthood.

To begin with they had only completed standard six. Then they went on with their education, first learning Italian and Latin so they could understand the further instructions they would receive. With hard work they managed to acquire so much Italian that they could study Latin and other subjects in that language. Being already somewhat advanced in other elementary subjects they concentrated on Italian and Latin, so that at the end of 1900 they had finished the Latin Inferior Grammar. In 1901 they also mastered the Superior Grammar with honors. In 1902, according to the syllabus of studies of the eternal city and all European university colleges, they tackled humanities, rhetoric, and the classics with success. In fact, Ngidi passed these examinations with greatest honors, receiving “Excellent” in classics (Latin and Greek), always being at the top of all his classes in all subjects. A rare fact! Of course, Greek students could not be beaten in their own Greek language.

According to the syllabus, in 1903 the students began the very important subject of philosophy. They studied a combination of matriculation and scholastic philosophy comprised of logic and metaphysics. In the same year they also studied higher mathematics, algebra, equations, geometry, and trigonometry.

Hard work indeed weighed heavily on all students, and our Africans were no exceptions. Nevertheless, both Africans were successful and obtained doctorates in this difficult subject of philosophy, after having passed the baccalaureate and licentiate.

In 1904, the most important subject had to be tackled, the climax of all priestly studies: sacred theology. That year they learned Catholic Dogma, de re sacrament aria, moral theology, church history, and the Holy Scriptures. At least four of the professors later became cardinals of the Sacred College: Faurenti, Sepicier, Lauri, and Caemonesi. The Africans also participated in the honors of their professors. Next came the hard test, the crowning of all the years of preparation-theological studies. As theology is the mistress and queen of all sciences, they continued to study it for the next four years, up to 1907.

The work continued at a steady pace and the two African students made satisfactory progress. Already in 1906 they passed their baccalaureate and licentiate exams in sacred theology, and in 1907 the younger African, Ngidi, succeeded in obtaining his doctorate in sacred theology as well.

Soon came the fulfillment of their most ardent desire, the day of their ordination to the holy priesthood in the Lateran Basilica by Cardinal Respighi, the vicar of Rome, on May 25, 1907. Both said their first masses the next day. The Rev. Julius Mbhele, who was the dean of the class, said his mass in the chapel of the Propaganda College. Fr. Andreas Ngidi chose to celebrate his first mass in the German national church, Del Anima, because he had great love and gratitude for the German missionaries in his country.

A month later, the two African priests, having visited some of the principal churches in Rome, began their journey home through Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and England. Shortly before they left, their group received an audience with the Holy Father, Pope Pius X.

Travelling by night and passing through the Sempione (Simplon) Tunnel they reached Althausen in Switzerland where they remained a couple of days with Landrat Giesler, whose son they had known many years before at Mariannhill. The Alps, as always, were snow capped. Naturally our African priests had to make use of the German language, since neither Italian nor English could help them converse with the German speakers in Switzerland.

From Switzerland the two black priests went to Stuttgart and Würzburg. At the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul they both held a service and distributed Holy Communion to many people. Würzburg had many benefactors who had helped in the establishment of Mariannhill and they had just started the mission school at Löhr. The African priests were surprised to see so much kindness and piety in German Catholics, almost surpassing that of Italian Catholics.

Leaving Würzburg a few days later they came to Cologne, the old Roman Agrippinae observantus [sic]. From here they visited some friends of Mariannhill as far away as Neuss, and everywhere they were treated with the greatest kindness and generosity. Indeed, the Germans who had founded Mariannhill could hardly fail to honor the fruits of their labors.

The time came to leave these friends of the missions. Soon our Africans crossed the border and came to Holland, another great mission country. Not many European countries can beat Holland in regards to missionary activity. It was late in the afternoon when the train crossed over the boarder and was on Dutch soil. After nightfall it was impossible to see much of beautiful low-lying Holland, the original homeland of the South African Dutch or Afrikaners. About an hour before midnight the train came to Flissingen where those crossing to England were to embark immediately. As soon as the arriving train stood still, the passengers for the British Isles left the train and boarded the waiting vessels for England. At about six a.m. they reached Plymouth and the passengers at once boarded trains for London. The Africans went straight to St. James were Dr. Gogginan, an ex-Propagandist, was waiting for them. There they said their Holy Mass between eight and nine a.m. and took some rest.

After lunch they began sightseeing, as they had never before been in London. They saw many wonderful buildings, churches and monuments. Father Gogginan was kind enough to take them about as a regular Cicerone of his London city. After three days’ short stay in London, the African clergymen embarked for South Africa, their dear home.

Their ship was the Tintagel Castle. This time, for a change, they came home via West Africa, around Cape Town. A few hours in Cape Town barely satisfied their curiosity to see more of that historical Cape of Good Hope. Their spirits were high and their hearts longed to see Durban and Mariannhill, the land of their birth, and their dear ones after their long absence, from 1899 to 1907. They could only visit Port Elizabeth and East London, as the ship was already rather late.

Andreas Mdonstwa Ngidi

Editor’s Note:

Here ends the autobiography of Andreas Mdonstwa Ngidi. The story ends abruptly because he died before finishing it. The autobiography was handwritten in an A5 note book and later typed into a ten paged document. The A5 booklet and typed manuscript are located in the Inkamana Monastery Archives, Vryheid: Andreas Ngidi: Clergy File #1:, “A. Ngidi, Autobiography of Mdontswa Andreas Ngidi” (undated).

Photo Gallery