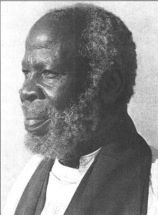

Kivebulaya, Apolo (F)

Apolo Kivebulaya– the “Pathfinder,” “Greatheart of ‘Africa,” “Apostle of the Pygmies,” and “African Saint”– was, as these the titles of some of his biographies suggest, much admired by a British missionary public in the mid-twentieth century. A Church Missionary Society (CMS) teacher from the year of his baptism in 1895, he left his native Buganda to work in the kingdom of Toro and in the Ituri Forest until his death in 1933. He was ordained as a deacon (1900) and priest (1903) in the Anglican Church and became canon of Namirembe Cathedral (1922). The widespread Baganda conversions were seen as a great missionary success story, in which Apolo epitomized and exemplified what CMS missionaries had prayed for: a native agent who showed lifelong commitment to the spreading of the Gospel and a willingness to sacrifice personal comfort and advancement for this goal. English biographies identified Apolo so closely with the missionary endeavor that he was largely forgotten as scholarly and missionary interests changed. From the 1960s onward, the emphasis on inculturation encouraged a focus on Christian leaders who had formed African churches distinct from missionary tutelage. Their independent communities were considered to be authentically African in a way that mission churches could not be. Yet Apolo’s work of preaching, teaching, praying, church planting, and training of evangelists is remembered in Uganda, where a number of churches and schools are named after him and he features in textbooks on Christian education from primary to A levels.[1] The Province de l’Eglise Anglicane du Congo regards him as its founder and commemorates the anniversary of his death every year in Boga.

Early Years

Apolo’s early life remains obscure, although he recorded that he was born in Singo between 1864 and 1870 and that his parents were Samueri Salongo Kisanzi, of the Nvuma clan, and Nalongo Tezira Singabadda, of the Ngabi clan. He was named “Waswa,” meaning “first boy of twins,” for he had a twin sister who died in infancy. He was briefly married, until his wife also died suddenly. He may have learned traditional healing practices from a relative. He also gained some familiarity with Islam when King Muteesa I (1856-84) adopted Muslim practices and required his subjects to do the same. The expansionist aims of the Baganda court and its openness to foreign influences and new technologies in the mid-nineteenth century meant that Muslim traders from the 1860s and Anglican and Catholic missionaries from 1877 were considered useful to Baganda aspirations. The conversion of courtiers in this environment ensured that committed religious affiliations were one with emerging political allegiances. Although Waswa lived far from court, a young man could not fail to find himself on one side of Ganda politics or another. He probably fought for the traditionalist and the Muslim factions during the wars of King Mwanga’s reign (1884-97). For sometime this association was evident in his wearing of a discarded outfit of a Nubian soldier and the subsequent bestowal of the name “Munubi,” signifying a person or soldier from the Nubian regiments.

During the wars more Ganda came into contact with literacy and with “religions of the book.” By the early 1890s Munubi had changed his affiliation to that of the group in political ascendancy- the Protestant, or Anglican, party. His baptismal name, “Apolo,” signals his transformation; it not only refers to the biblical figure but also was the name of the influential Protestant prime minister, Apolo Kaggwa. He was of peasant stock and was considered an unprepossessing character at first, but his Christian commitment gained him the patronage of influential Ganda leaders, most particularly the county chief and lay church leader Ham Mukasa.[2] He obtained the name “Kivebulaya,” meaning “the thing of Europe,” when he began wearing the jacket of a British soldier with a kanzu, the long white Ganda robe. The changes of name and dress are indicative of his shifting alliances during this time.

From his baptism in 1895, Apolo’s life is relatively well documented. During a period of over thirty years, he sporadically kept a diary, and he wrote his own short autobiography. Some of his correspondence is also extant.[3] Apolo appears in missionary records as a colleague and companion of European missionaries. Apolo’s becoming an employee of CMS ensured that he can be traced in the historical records, unlike some other African missionaries of his era.

Tooro

Apolo’s appointment as “church teacher” in Tooro (formerly spelled Toro) in September 1895 was linked with the political influence of the Ganda. The evangelization of Buganda’s neighboring kingdoms has been understood, to a greater or lesser extent, to have been propelled by Ganda imperialist ambitions in a complex and often tense partnership with British colonial and missionary interests. The kingdom of Tooro had seceded from Bunyoro in the 1830s and had allied with Buganda in the 1890s to maintain its independence from Bunyoro. The king, Daudi Kasagama, who owed the retention of his position to the Ganda and the British, requested evangelists from Buganda. In such a situation the decision by the Mengo Church Council, chaired by Apolo Kaggwa, to respond to this request from Toro was a political act. CMS and the White Fathers had made an informal agreement that Toro would be a Catholic area, but the Anglican bishop, Alfred Tucker, condoned the church council’s decision on the grounds that it was made by the local church and not the mission agency. Apolo was among the second group of evangelists to go to Tooro with the support of Ham Mukasa.

The Toor elite in Kabarole had a keen interest in becoming church readers. However, there was a false start to Apolo’s work when the over-zealous colonial official, Captain Ashburnham, assumed that Apolo, his fellow catechists, and the king were involved in gun-running. Kasagama escaped to Mengo, but Apolo and two other teachers were arrested, imprisoned, and then returned to Mengo. Ashburnham was reprimanded for his heavy-handedness, Kasagama was baptized, and Apolo was released without charge. In March 1896 he returned to Kabarole, and later he was sent to the Konjo at Nyagwaki, in the Rwenzori foothills. This was the first of many postings, as CMS teachers were regularly moved from place to place. It also demonstrates the royal patronage of Christianity. The Konjo were considered part of the colonial kingdom of Tooro, although they had a distinct language, customs, and polity. They had sheltered the queen mother when she had fled Banyoro raids, and as a sign of her gratitude she sent them an evangelist.

Apolo’s next posting, to Boga (formerly spelled Mboga), was likewise integral to regional political relationships. King Tabaro of Boga on the western Semeliki escarpment visited Kasagama to develop relations to mitigate against the vulnerability of being on the edge of the rapacious Congo Free State. He was introduced to the spiritual novelties of Christianity and was encouraged to accept specialists of its technicalities. In December 1896 Apolo joined Sedulaka Zabunamakwata, replacing Peter Nsguba. The response to their teaching was swift and positive: inhabitants of Boga learned to read and were catechized, and the first baptisms of Boga Christians took place in April 1897.

The speed of early acceptance of Christianity in Boga is often overlooked because of the prominence in missionary literature given to Apolo’s persecution story, in which his life was threatened and he was taken to Fort Portal and imprisoned for several months before being released. The story is often recounted as a tale of good religion fighting bad superstitions, and of perseverance in adversity. Yet one may also interpret Tabaro’s attack on Apolo as that of a leader who was caught in new circumstances, unsure how best to act for his people, and conscious that his spiritual role in the community was undermined by a new class of specialists. Apolo was invited back by Tabaro once he was released, and Tabaro was baptized in April 1898, taking the name “Paul.” Apolo’s diary suggests that these events were a turning point in his ministry, in which he acknowledged the power of prayer and the ability of God to aid him.

God strengthened me and I did not get weak in Our Lord’s work. But God helps those who believe in him for I believed and he rescued me. And he also hears the prayers of his people as the Ganda say…you seek for advice from the one who has gone through the same thing.[4] I too was caught and put in chains but because of prayer, they let me go. My God helped me greatly and my enemies could not overcome me… I asked him for so many things and I saw them. For I always feared that in those places to which I was sent, those people may not like Jesus Christ. They believed when I prayed and they turned back as soon as I stopped praying.

Boga would remain an important place in Apolo’s life, perhaps because of the dramatic events he experienced there. But in August 1899 he was sent to Kitagwenda in Tooro, before being recalled to the central mission station at Kabarole/Fort Portal. He was ordained deacon on December 21, 1900, benefiting from Tucker’s policy of early ordination for those who demonstrated good service to the church, regardless of a lack of formal theological education. During 1901 he was based for a few months at Butti, the most significant mission in Tooro after Kabarole. By the end of the year, however, he moved back to Kabarole, and it is his work here that Fisher describes so effusively:

Of our good friend Apolo and his work one cannot speak too highly. He…is a great teacher and a true soul-winner. He is very keen to learn and spends all his spare time in self-improvement of some kind or other. The Thirty-Nine Articles he committed to memory in less than a month, and on receiving the [prime minister] of Buganda’s new history of that country stayed up all night reading it, so good was the feast of new literature.[5]

Fisher’s words not only describe a dedicated deacon of the Native Church of Uganda, but also indicate what attributes European missionaries considered exemplary and the way in which Apolo educated himself as an Anglican and as a modern Ganda. The image of Apolo Kivebulaya so gripped by Kaggwa’s history of Buganda kings– the first of a number of Kaggwa’s books that drew upon the history and customs of the Ganda- that he was unable to put the book down suggests that he was imbibing ideas on nationhood and good citizenship; such ideas drew on a contemporary Ganda and Christian interpretation of the past ii order to steer a progressive course to Christian modernity.[6] Other accounts describe his attention to Paul’s missionary journeys, which he saw as an example for his own itinerations.[7] Apolo’s attention to the Thirty-Nine Articles provides the background to his daily practice of corporate prayer and his commitment to the participation of others. Fisher provides the following vignette:

I can hear him all hours of the day, teaching hymns, praying with the people and doing true pastoral work. At sunrise and at sunset he gathers everyone around, including passers-by to join him in morning and evening prayer, using the psalms for the day. He reads his own verse in a loud voice and the congregation’s in a low voice, just to encourage those not quite sure of the words, never forgetting the “Gloria” which they sing for all they are worth. The great advance of the work at Butiti has been entirely due to his industry, zeal and holy life. I am deeply thankful to have such a fellow-worker.[8]

Apolo inculcated Anglican norms in Kabarole, performing daily offices and encouraging others to participate. He also introduced innovations: the services appear to have taken place in the open air or his house, not in church, and he taught the words as he went. In Boga he took over the sacred drum to call people to Christian worship. The picture Fisher paints of Apolo fits with the history of Ganda influence in the western kingdoms. By 1900, however, Tooro public opinion was turning against Ganda involvement in the kingdom. Yet Apolo appears to have been unaffected by growing resentment and was wholeheartedly supported by the Toro Church Council. Although his biographers often suggest he was unconcerned with politics, his work demonstrates a deliberate respect for and interest in the lives and customs of those among whom he worked. His involvement in translation, for example, shows that his life in Tooro and his Protestant biblicism caused him to take different approaches from those of many of his Ganda and missionary peers.

Translation

Apolo had begun work on a primer, catechism, prayer book, and Gospel of Matthew in Nyoro. He argued for the whole Bible to be translated into Nyoro. This issue, however, was controversial. Protestant missionary belief in the importance of vernacular translations for evangelism was balanced by concerns about the specialized and time-consuming nature of the work. In Uganda it was also influenced by concerns over political and ecclesiastical unity and the assumption of a hierarchy of languages and cultures. It seemed to many Europeans that Luganda and the Ganda were superior conductors of Christianity to be used in other parts of the protectorate.[9] Apolo Kivebulaya and H.E. Maddox, who took over the translation work, both disagreed firmly with this idea. In 1900 they petitioned the CMS secretaries in London for support in translating the Bible. Maddox, in his letter, identifies Apolo as the translator of Matthew’s gospel[10] and describes him as “the most influential missionary” in Tooro.”[11] Apolo’s letter argues from his own experience as reader and evangelist.

When I went to Toro, I taught them in Luganda but they could neither hear nor understand what I told them, and I also did not understand them. . . . I then saw it right to learn their language. . . I put in much effort to teach them religion in Luganda. . .[but] when they read the book in Luganda they could not understand it and their hearts were not ready to get saved. . . .I remembered that we, Ganda, were at first taught Kiswahili but I never understood what they were teaching. When I read alone, I never understood, but when they brought the Luganda book I understood fully. . . . I want with all my heart the Old and New Testament in Lunyoro.[12]

He knew literacy was highly valued and that literacy in one’s own language was much easier to achieve. Apolo’s petitioning for a Nvoro translation shows that he distanced himself from the ambitions of his compatriots and stood against the wishes of the Mengo Church Council, which was arguing for greater use of Luganda.[13] His probable involvement in the translation of Mark’s gospel into Konjo (1914)[14] and his initiative to produce a primer and Gospel of Mark for the Mbuti (1933)[15] demonstrate the importance he placed on vernacular translations. In this last translation he and his team almost certainly worked from the Nyoro Bible (1912) he had argued for, not the Luganda translation.

Boga and the Forest

The missionary calling beyond one’s own people and place was further illustrated in Apolo’s life by his more permanent association with Boga and the Ituri Forest from 1916. He continued his role as cultural broker and mediator of ideas, introducing a Christianity that was entwined with entangled Ganda and British ideas of advancement and progress, yet doing so in a way that resonated with those to whom he preached. The Boga area had seen considerable disruption. The colonial boundaries were disputed until 1910, when Boga’s position on the west side of the Nile-Congo watershed made it Belgian territory, subject to a colonial authority that prioritized Belgian Catholic missions. It lost its position as a significant trading post of ivory and rubber and was reduced to a small village at the periphery of a vast colonial country. The Belgian authorities were wary of British influence and often delayed CMS requests for access, although Apolo was permitted to work there.

In 1916 he gave up a year’s sabbatical in Buganda to return to the village because he had heard that the Christians were discouraged and their numbers were dwindling. His diary for this year and the following one have some unusually detailed passages, suggesting that the events were significant for his continued commitment to Boga. He found the small Christian group much depleted and returning to polygamy, beer drinking, and the traditional practices he had preached against.[16] They were intimidated by Sulemani Kalemesa, installed by the Belgian authorities as subchief of Boga, who accused them of having British colonial sympathies. In Apolo’s account Kalemesa is presented as cruel, autocratic, and lacking true faith; his rule is spiritually detrimental.[17] Apolo calls on the power of the Almighty, and his prayer for the downfall of Kalemesa is answered.

We prayed saying, “O God, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, we put forth to you this person so that you may do to him what- ever you wish, whether to take him away or to let him live and convert him, for if you don’t interfere he is going to lead many astray and kill them.” In this God the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit helped us, and Chief S. Kalemesa died soon after. These prayers were carried out in the year 1916, and in August he fell sick and he died. Then God helped us and we got a Christian King. . . . At present many people have been converted and they regularly come to church and they confess their sins, and in all these things it is God who helps us.[18]

The defeat of Kalemesa and growth of the Boga church appear to have given Apolo courage, and he decided to stay in the area more permanently. Apolo was the only African church leader in the region, and the church suffered occasional harass- ment by the authorities. After the brief ministry and subsequent imprisonment of Simon Kimbangu in the west of the country in 1921, Apolo was observed closely by the administration. As an African he could make no legal representation on behalf of the Boga mission to the Belgian colonial authorities and relied on European CMS missionaries in Uganda to do so. Nevertheless, for the next sixteen years he developed relations with the Hema, the Giti, the Konjo, the Talinga, and the Lese; he also established another center at Kainama. His biographers place particular emphasis on his relations with the Mbuti pygmies of the forest, yet his sustained contact with them began only in 1921. Nevertheless, Apolo appears to have developed a great affection for them, for he enjoyed spending time with them and listening to their stories.

During this time he also developed a school at Boga, emphasizing particularly the education of girls. He itinerated with groups of young people, whose strong personal loyalty to him was instrumental in the flourishing of the church after his death. He worked hard at cross-cultural relations, making friends with peoples his fellow Baganda looked down upon. Yet he maintained expectations of modernization and change that had been significant in the conversion of Baganda since the arrival of Alexander Mackay of the CMS in 1878. By 1931 Apolo had developed a network of small Anglican congregations within a radius of a three-day walk from Boga. He was responsible for 42 churches, 58 native teachers, and 1,426 baptized Christians, among six ethnic groups.[19]

In 1933 Apolo entered the hospital in Mengo and was discovered to have a terminal illness. He made a final visit to Boga and requested that he be buried there in a way contrary to Ganda custom: with his head pointing away from his homeland and into the forest. His simple grave can be found next to the cathedral. While the details of his burial has been variously interpreted, his return to Boga is generally understood as a mark of his continual self-sacrifice.[20] On hearing of his death in 1933, the Uganda standing committee minutes noted the following: “To know him was to love him…He was the genuine apostle of the type of St Paul…he was emphatically one who has hazarded his life in the service of the Lord Jesus…His gentleness, his sympathy, the transparent sincerity of his life, and the domination of his will over his ageing body presented an outstanding example of the grace of God in a chosen vessel.”[21]

Conclusion

Apolo has been praised for apostolic saintliness and ascetic spirituality, yet such plaudits can overlook the significance of his life as lived in the midst of a rapidly changing society. The role of emerging colonial polities and Apolo’s alliance with the elites in Buganda and in Toro form part of the development of a particular Christian tradition. Like other missionaries, Apolo Kivebulaya was an agent of social and cultural change who was part of complex, shifting inter-religious dynamics, operating across disputed boundaries and adapting Christian belief and practice to historical contexts. He worked in remote places among peoples who were despised by their neighbors. He was loved and honored by the communities who accepted his preaching and established churches. They appreciated his tireless itineration and his interest in them. Yet his influence was rarely limited to the local. He was a regional actor entangled in transnational projects to which he contributed and the perceived benefits of which he transmitted to others. He demonstrates a comprehension of Christianity as a religion that is both locally and personally focused and connects beyond human boundaries of ethnic groupings and state borders.

Emma Wild-Wood

Sources

Katongole, G. R. Apolo Kivebulaya owe Mbooga. Kampala, 1952.

Lloyd, Albert B. Apolo of the Pygmy Forest. London: CMS, 1923.

——-. Apolo the Pathfinder: Who Follows? London: CMS, 1934.

——-. More about Apolo. London: CMS, 1928.

Luck, Anne. African Saint: The Story of Apolo Kivebulaya. London: SCM, 1963.

Pirouet, Louise. Black Evangelists: The Spread of Christianity in Uganda, 1891-1914. London: Rex Collins, 1978.

Wild-Wood, Emma. “The Making of an African Missionary Hero in the English Biographies of Apolo Kivebulaya (1923-1936).” Journal of Religion in Africa 40 (2010): 273-306.

——-. Migration and Christian Identity in Congo (DRC). Leiden: Brill, 2008.

——-. “Powerful Words: Reading the Diary of a Ganda Priest.” Studies in World Christianity 18 (2012): 134-53.

——-. “Saint Apolo from Europe, or ‘What’s in a Luganda Name?’” Church History 77 (2008): 1-23.

Archive material relating to Apolo Kivebulaya exists in the following places:

- Apolo Kivebulaya Collection, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- British and Foreign Bible Society Archives, Cambridge University

- CMS archives, Birmingham University, Birmingham, U.K.

- Church of Uganda Archives, Uganda Christian University.

Notes

- J.B. Mwesiga, “Christianity in the East African Environment,” in MK Standard Religious Education, Book 4 (through to A level), rev. ed. (Kampala: MK Publishers, 2012). For the curriculum development work of MK Publishers, see http://mkpublishers.com/about_us.php.

- G.R. Katangole, Apolo Kivebulaya owe Mbooga (Kampala, 1952), 7-9.

- Apolo Kivebulaya collection, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda (henceforth MUK).

- The Luganda proverb states literally, “The remedy for burns is known by the person who has suffered them” (Apolo Kivebulaya Diary, 1898, MUK).

- A.B. Fisher, November 30, 1901, in CMS Annual Letters, 1901-1902 (London, CMS, 1902).

- See Michael Twaddle, “On Ganda Historiography,” History in Africa 1 (1974): 85-100; John Rowe, “Eyewitness Accounts of Buganda History: The Memoirs of Ham Mukasa and His Generation,” Ethnohistory 36 (1989): 61-71.

- Account of Apolo Kivebulaya by Bishop Aberi Balya, MUK.

- A.B. Fisher, November 30, 1901.

- Frank Rowling, “The Luganda Language,” CMS Archives, Birmingham Univ., Birmingham, U.K. (henceforth CMSA), G3A7 0.

- Maddox took little credit for the work himself, although he is usually considered to be the translator. He took the lead on the complete translation, although he names Yosiya Kamubigi, Aberi Balya, and Zakayo Musana as his colleagues (August 2, 1911, British and Foreign Bible Society Archives, Cambridge Univ. [henceforth BSA], E3/3/454).

- September 9, 1900, Maddox to CMS, London, CMSA.

- September 9, 1900, Apolo Kivebulaya to CMS, translated by George Mpanga (and Maddox), CMSA.

- See Holgar Bernt Hansen, Mission, Church, and State in a Colonial Setting: Uganda, 1890-1925 (London: Heineman, 1984), 383-95.

- Correspondence with Paul Hurlburtof Unevangelized Africa Mission (subsequently the Conservative Baptist Foreign Missionary Society), 1932, BSA, E3/3/433.

- Correspondence between Robert Kilgour, A. B. Lloyd, Apolo Kivebulaya, and Edwin Smith, BSA, E3/3/629, file5c; and Edwin W. Smith, BSA, F3 and “The Language of Pygmies of the Ituri,” Journal of the Royal African Society 37, no. 149 (1938): 464-70.

- Apolo Kivebulaya diaries, January 10, 1916, MUK.

- Ibid., April 5, 1916.

- Ibid., January 4, 1917.

- 2bp10.1, 1931, Willis Report, Church of Uganda Archives, Uganda Christian University (henceforth COUA).

- Emma Wild-Wood, Migration and Christian Identity in Congo (DRC) (Leiden: Brill, 2008), chap. 8.

- Native Anglican Church Council Minutes, July 6, 1933, COUA.

About the Author

Emma Wild-Wood, co-director of the Center for the Study of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, is the author of a critical biography, The mission of Apolo Kivebulaya: Social Change and Religious Encounter in the Great Lakes 1865-1935 (James Currey, 2020). She is professor of African Religions and World Christianity at the University of Edinburgh. Previously she taught in D.R. Congo and Uganda as a CMS mission partner. [email protected].

This article, uploaded in 2023, is shared with permission from Wildwood, E. “A Biography of Apolo Kivebulaya.” International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Vol. 38, No. 3, (July 2014): 145-48.