Sematimba, Mika

Mika Sematimba was Uganda’s first Protestant convert to travel to England as a missionary, arriving in 1892.

Mika Sematimba was Uganda’s first Protestant convert to travel to England as a missionary, arriving in 1892.

Sematimba was born in Ssingo, a county of Buganda, but only lived there until the age of eight when his uncle gave him away to serve the Namasole.[1] Barely thirteen years old, he was again given away as a gift to Muteesa I, moving to the king’s palace, where he soon caught the Kabaka’s attention and was appointed a sub-chief under the storekeeper.[2]

His interest in learning began at Muteesa’s court, learning Swahili and the Koran after Muteesa required Baganda to learn the few lessons Zanzibari-Arabs offered. It was the fashion then for all boys to learn the Arabic alphabet and the few prayers offered.[3] When the Catholic White Fathers arrived in February 1879, Sematimba enrolled in their program and was, for a time, Simeon Lourdel’s student.

The turning point for Sematimba came while on a trip to the coast in 1882, where Muteesa had sent him to deliver a gift of ivory to Bargash bin Said, the Sultan of Zanzibar. There, he met Kitakule (who also became Henry Wright after baptism), a fellow Muganda enrolled in the Universities’ Mission program leading to baptism. Kitakule told Sematimba how he was learning to read and write, which excited him promising to enroll in Uganda’s Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission once he returned home.[4]

Following his promise, he regularly visited Natete, Uganda, the location of the CMS mission when he returned, and in December 1883, he was baptized by Rev. Philip O’Flaherty, choosing Micah as his baptismal name, localized to Mika.[5] He was part of the rapid church growth period that started with the baptism of March 18, 1882, that by the end of 1884, the number of Christians had increased to eighty-eight for a missionary team of three – O’Flaherty, Alexander M. Mackay, and from the spring of 1883, Robert P. Ashe.[6]

On October 10, 1884, Muteesa, for whom missionaries had first come to Uganda, died and was succeeded by his son, Mwanga II, whose first four years as Kabaka were characterized by persecution. Sematimba remained as a sub-chief under Mwanga until it became impossible for him to do so due to his Christian beliefs and belonging. By the time he sought refuge in Kabula, Ankole, Sematimba had survived death on three occasions. [7]

At 25, he was elected an elder of the inaugural church council comprised of twelve baptized Ugandans. The council constituted in July 1885 came into existence out of fear that Mwanga, whose Kabaka-ship was killing Christian converts, might soon expel missionaries from Uganda, who were constantly afraid for their lives. As elders, they were authorized to conduct service and preach in the absence of CMS missionaries.[8]

While Mwanga did not expel anyone except Mackay, who, on the advice of Muslims, was asked to leave Uganda in exchange for Rev. E. Cyril Gordon in 1887, persecution intensified. On October 29, 1885, James Hannington, on his way to Uganda as the first bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa, was killed in southern Busoga by Luba, a Musoga chief, on Mwanga’s orders. [9] The Roman Catholic martyr Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe, the head of royal servants of the Kabaka like Sematimba, was ordered to be burnt alive on November 15, 1885.

One day, the executioner seized Sematimba’s mat and bark cloth, finding books in them which he forwarded to Mwanga, who in turn sought the advice of the Katikkiro on how to deal with him. When news of the decision got to him, he excused himself before he was caught taking his family to safety before fleeing to Ankole, where Christians were establishing a refuge. Sematimba told Rev. R. H. Walker he stayed in Ankole for two years.[10]

With his fellow elders, Kitakule and Sembera Mackay, he left Ankole to deliver letters to Mackay in Usambiro (present-day Tanzania), one of them from Mwanga, whose plight had changed after he was dethroned by a combined force of Christians and Muslims in April 1888. Sematimba heard this news in September 1888 and immediately decided to return to Buganda, only to find Christians hunted down for death by Muslims, thereby turning back.[11]

On October 4, 1889, Christians defeated Muslims, re-installing Mwanga on the throne seven days later marking the end of exile for Baganda Christians. In appreciation for helping him reclaim his throne, Mwanga rewarded Christian leaders with chieftaincies, but Sematimba, Kitakule, and Sembera declined chieftaincies, preferring to commit fully to the Lord’s work.[12] He, however, accepted to become a Makamba in time for his landmark journey to England.[13]

Sematimba was one of Uganda’s first six Protestant catechists commissioned on January 20, 1891, by Bishop Alfred R. Tucker, on his first trip to Uganda as the third bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa. [14] Without an established education system in Uganda, catechists were possibly the most educated Ugandans of the day.

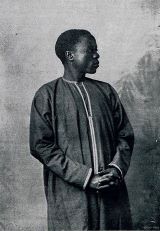

Figure 1: Mika Sematimba and Rev. R. H. Walker, with whom he went to England in 1892[15]

Under the auspices of the CMS, in the care of Walker, Sematimba arrived in England on November 1, 1892, spending months there, attending events and meetings.[16] In January 1893, he was at a gathering of the Young Clergy Union, where he requested missionaries to be sent to Uganda, citing Matthew 9: 35-38. On March 21, 1893, he and Walker were interviewed by the CMS Committee of Correspondence on the state of the Uganda mission, after which they spoke to the CMS Lay Workers Union at the Albert Hall in Sheffield, where he was presented with a splendid hunting knife as a memento.

On May 18, 1895, an unprecedented ten English missionaries were sent to Uganda, five of whom were the first female missionaries to Uganda. Sematimba was assigned to welcome them. In his book Eighteen Years in Uganda and East Africa, Bishop Tucker writes, “At Ngogwe, Mika Sematimba met me with a welcome letter from the king and greetings to the ladies.” [17]

Sematimba never progressed any further in church positions when he returned from England, but his work continued to be at the intersection of church and state. He received nearly twelve square miles in the Buganda Agreement of 1900 as a chief, part of which was in Budo, Busiro county, where he started a school and built a church.[18]

He was a polygamist who married two wives, Rebecca and Elizabeth.[19] From his first wife, Racheal, Dinah, and Noah, survived to adulthood, and Grace, Emily Nalongo, and Drummond from his second wife. Drummond became a sub-chief in Gomba.

Sematimba died in August 1951 and was buried at his Kisozi estate. His son of the same surname, whose Christian name was Noah succeeded him.

Kimeze Teketwe

Notes:

-

Audrey Isabel Richards, The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972), 48. Namasole is the Luganda word for Queen Mother, Luganda being the language of the Baganda people, the ethnicity comprising the East African kingdom of Buganda.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 20, Issue 231. 1893. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, http://www.churchmissionarysociety.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/CMS_OX_Gleaner_1893_03, 37. Kabaka is king in Luganda.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, 37.

-

J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 70.

-

Audrey Isabel Richards, The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972), 49.

-

J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 31.

-

Audrey Isabel Richards, The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972), 48-49.

-

J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 161.

-

Musoga is one person from Busoga, an ethnic group on the eastern side Buganda.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, 38.

-

J. A. Rowe, “The Purge of Christians at Mwanga’s Court,” The Journal of African History 5, no. 1 (1964), 55.

-

J. D. Mullins and Ham Mukasa, The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904), 69-70.

-

Makamba is a sub-chief role under the Mugema responsible for installing a new Kabaka.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 16. 1891. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, http://www.churchmissionarysociety.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/CMS_OX_Intelligencer_1891_02, 419.

-

The Church Missionary Gleaner, 37.

-

The Church Missionary Intelligencer, Volume 18. 1893. London: Church Missionary Society. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Church Missionary Society Periodicals, http://www.churchmissionarysociety.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/CMS_OX_Intelligencer_1893_05, 398.

-

Alfred B. Tucker, Eighteen Years in Uganda and East Africa (London, 1911), 26.

-

Audrey Isabel Richards, The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972), 62.

-

While the church will marry a person to a single woman, it is common for men to take on other women as ‘wives’ after the official marriage.

Sources:

Ashe, Robert P. Two Kings of Uganda or Life by the Shores of Victoria Nyanza. Being an Account of a Residence of Six Years in Eastern Equatorial Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1890.

Church Missionary Society Periodicals. Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Adam Matthew Digital.

Mullins, J. D., and Ham Mukasa. The Wonderful Story of Uganda; to Which Is Added the Story of Ham Mukasa, Told by Himself. London: Church Missionary Society, 1904.

Richards, Audrey Isabel. The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972.

Rowe, J. A. “The Purge of Christians at Mwanga’s Court.” The Journal of African History 5, no. 1 (1964): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700004503.

Tucker, Alfred Robert. Eighteen Years in Uganda & East Africa … with Illustrations from Drawings by the Author and a Map. with a Portrait. London: Edward Arnold, 1908.

Bibliography

Ashe, R. P. Chronicles of Uganda. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1894.

Church Missionary Society Periodicals. Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Adam Matthew Digital.

Mullins, J. D. The Wonderful Story of Uganda. London: Church Missionary Society, 1904.

Richards, Audrey I. The Changing Structure of a Ganda Village: Kisozi, 1892-1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1966.

Tucker, Alfred, Eighteen Years in Uganda & East Africa. Vol I-II. London: Edward Arnold, 1908.

About the Author

This biography, submitted in March 2023, was researched and written by Kimeze Teketwe, a Luganda lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Originally from Uganda, East Africa, Teketwe holds graduate degrees in missiology and international educational development from Fuller Graduate School of Intercultural Studies and Penn Graduate School of Education, respectively.

Additional Photos