Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Smith, Edwin W.

Edwin William Smith who became famous as a missionary/anthropologist with linguistic talents, was born at Aliwal North, South Africa, on September 7, 1876.[1] His parents were missionaries of the Primitive Methodist Connexion, a movement that began in the early nineteenth century and became one of the main branches of British Methodism. Edwin Smith’s father, John Smith (1840-1915), went to Aliwal North in 1874 and spent ten of the next fourteen years there. Returning to London, he became secretary of the Primitive Methodist Missionary Society in the 1890s and president of the Primitive Methodist Conference in 1898.

Edwin William Smith who became famous as a missionary/anthropologist with linguistic talents, was born at Aliwal North, South Africa, on September 7, 1876.[1] His parents were missionaries of the Primitive Methodist Connexion, a movement that began in the early nineteenth century and became one of the main branches of British Methodism. Edwin Smith’s father, John Smith (1840-1915), went to Aliwal North in 1874 and spent ten of the next fourteen years there. Returning to London, he became secretary of the Primitive Methodist Missionary Society in the 1890s and president of the Primitive Methodist Conference in 1898.

As a young person Edwin Smith showed few signs of academic prowess and found an office job in London. In his spare time he roamed through his father’s large library and read the works of John Colenso and other progressive writers. This reading undermined his faith, but a local minister led him to view Christianity pragmatically, “as a life to be lived.”[2] He also read books about the exploration of Africa, and as his longing to return to Africa increased, he realized in 1895 that there was an opportunity for service as a Bible translator in a new mission among the Ila of central Africa. He learned Greek at Birkbeck College and spent a year acquiring basic medical skills at Livingstone College, in London’s East End. Then in 1898 he returned to Africa and spent a few months in Lesotho with the Paris Evangelical Mission. The enthusiasm and expertise of Rev. E. Jacottet of Thaba Bosiu inspired him to make his own studies of Bantu languages and cultures.

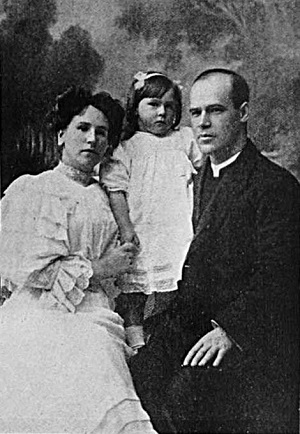

Edwin Smith and his fiancee, Julia Fitch, a teacher, were married at Cape Town on the same day that Julia arrived in South Africa, October 3, 1899. The Smiths intended to leave for central Africa in 1900, but the tense political situation of 1899, which led to the Second Anglo-Boer War, kept them at Aliwal North until 1902. Smith ministered in the Primitive Methodist circuit, continued his language studies, and acquired practical skills in the mission workshops. Their son Thabo (“joy”) was born in January 1902, a few months before they set off for Zambia.[3]

Missionary Work in Central Africa

When the Smiths arrived at Nanzhila, on the edge of Ila country in Zambia, the Primitive Methodist mission needed further stimulus. Smith applied himself energetically to evangelism, education, and building, but his most telling contribution to mission development came through his linguistic work. During his first tour among the Ila (1902-7), he published St. Mark’s gospel in Ila (1906), prepared hymns, services, and Old Testament stories in Ila, and wrote an Ila grammar, Handbook of the Ila Language (1907). This thorough piece of work is still admired for its accuracy and wealth of detail.

Smith took a keen interest in the religious beliefs of African people and published his first thoughts on this subject in 1907 in an overview article, “The Religion of the Bantu.” In the same year he followed this with a published lecture, “The Secret of the African,” which concentrated on Ila religion. In seeking to reach his people with the Gospel, Smith used their traditional beliefs as stepping-stones to Christian faith. He believed that Africans had discovered religious truths, and in his preaching he introduced, for example, their praise names for God and then went on to preach Christ. In finding points of contact, he anticipated the approach toward animistic religions that was taken at the World Missionary Conference at Edinburgh in 1910.

Edwin and Julia Smith, after a two-year furlough, returned to Zambia in 1909 and opened a new mission in the heart of Ila country at Kasenga. Edwin did more building–a school, two houses, and other buildings–and continued his Ila New Testament translation; by the end of his term of service in 1915, the New Testament had been completed. During these years, realizing that language has to be understood in its cultural context, he made anthropological studies of the Ila people with A. M. Dale, a district officer. Knowing that administrators and missionaries alike needed to understand the people, they hoped their research would help future workers. World War I delayed publication, but the two-volume Ila Speaking Peoples of Northern Rhodesia (henceforth ISP) appeared in 1920. Students used it as a standard text for many years. In 1968 Elizabeth Colson, who did important anthropological research in central Africa, described the ISP as “one of the great classics of African ethnography… a precious heritage of African history.”[4]

The Smiths returned to Britain in 1915, and Edwin served on the Western Front as an army chaplain. His experiences and reflections in Africa laid the foundations for his future participation in several aspects of African studies over the next forty years.

Varied and Integrated Studies

Ill health forced Smith out of the army in 1916. As he had fundamental disagreements with his mission’s policies, he did not return to Africa. However, the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS), an interdenominational organization, seconded him to work as its agent for Italy. After five years in Rome he returned to Britain as secretary for western Europe but was soon transferred to the BFBS Bible House to take charge of the society’s literature. From 1923 to 1932 he published reports and edited magazines for adults and children. Then in 1932 he was given responsibility for Bible translation as editorial superintendent.

Translation had been his chief missionary interest, and as well as being a translator, he had written a splendid book entitled The Shrine of a People’s Soul (1929), in which he drew on his own experiences in Africa and anthropological insights. He expressed the view that translation should be true to the original text, understandable to the hearer/reader, and as beautiful as possible. Not surprisingly, Smith looked for reader-friendly translations when he was responsible for translation policy. He was impressed by Basic English, a simplified form of English with a limited vocabulary of 850 words, and was on the committee that produced the Bible in Basic English. He advocated Basic English as a tool for translators and published books in Basic English, including his own version of John’s gospel (1938).

Before retiring from the Bible Society, Smith toured India (1938-39) to assess the need for new or revised versions. Although some of those interviewed, including Gandhi, thought it better to retain archaic versions, Smith insisted that modern versions were much needed. He discussed the matter with the veteran missionary C. F. Andrews and the poet Rabindranath Tagore, and the latter agreed to help in making a new Bengali translation. World War II hindered implementation of Smith’s suggestions, but his report was highly regarded and did influence later policy.[5] Illuminated by anthropology, Smith’s approach has been followed in the professional era of translation (said to have begun in the 1940s with the arrival of Eugene A. Nida at the American Bible Society). Smith is recognized as a precursor of the modern era, and common-language Bible translations are part of his legacy.[6]

Missiology

Smith knew that translation and missiology are interrelated. His missiology involved translation, not only of languages, but also of cultures. He believed that the form in which Christianity was expressed in any culture should be appropriate to that culture, and he opposed the belief that traditional customs were necessarily wrong. It distressed him that so many believed that one could not be both Christian and African, and in his wide-ranging Hartley Lecture, The Golden Stool (1926), he promoted radical Africanization of Christianity. He suggested that African baptismal names, dances, drama, indigenous music, and the Christianization of initiation and marriage ceremonies would help Christianity in Africa to be more rooted in African experience. He was quite aware that foreign features could be accepted and adapted by Africans, but he was adamant that Africans should decide what to accept, adapt, or reject. He realized too that the Western proclivity for domination needed to be controlled. Missionaries, for example, might introduce the faith, but he was convinced that they should not impose their expatriate forms as norms. Indeed, he believed that if Christianity was identified with Western imperialism, it was likely to be rejected when the empires fell. This thought led him to argue that there was a supreme need “to purge our missionary enterprise of all taint of cultural imperialism.” The first principle, he declared, “is Christ, not western civilization.”[7] In 1926 he wrote: “Missionaries are not a permanent factor in the life of Africa-they will one day (the sooner the better) disappear because no longer needed. It is not their business to decide what form African Christianity shall take.”[8] Although he wanted to reduce the influence of missionaries, Smith respected the work of his predecessors and wrote biographical studies of Robert Moffat, the Mabilles, Daniel Lindley, and Roger Price.[9] These biographies are notable for the way he wrote about his subjects in their social and historical contexts.

In translating Christianity into African languages and cultures, Smith contended that Christian theology in Africa should be adapted to African thought forms. Some missionaries in India, notably John Farquhar in The Crown of Hinduism (1913), saw Christianity as the fulfillment of Indian hopes, and Smith saw the potential of this approach for Africa. It had been achieved sporadically in various parts of Africa, as at Kasenga under his ministry, but his achievement in African Beliefs and Christian Faith (1936) was to present the first fully worked out example of African Christian theology many years before it became an established style of theology.[10] The work reflected his wide knowledge of the Bible and of African religions and cultures, and it showed how African beliefs, although fulfilled by Christianity, gave insights that enabled a deeper understanding of the Christian faith. African Christian theology has become a fact of African Christianity and has attracted many followers. Although it came into prominence after his death, Smith is rightly regarded as its fons et origo.[11]

African Religions

After his early studies of African religions in 1907, Smith continued his fieldwork and reading in this area and addressed a missionary conference in 1914 on the Bantu conception of God. He believed that the concept of God was the best link between African religious traditions and Western Christianity but recognized that such a concept was part of a larger religious tradition in Africa. He used this wider context in the ISP, where he devoted 134 pages to Ila religion and used a fourfold analysis: dynamism, souls, divinities, and Leza (the Supreme Being). “Dynamism,” a term found in the work of anthropologists van Gennep and Marett, was his preferred term for what was usually known as magic. It described belief in an underlying energy or force, akin to mana, which people tried to control through charms, medicines, taboos, and witchcraft.

Smith went on to write more widely about African religion and did much to develop and publicize the subject throughout his life. He used his fourfold scheme in his first book on African religion, The Religion of Lower Races (1923); the unfortunate title for this useful book was not given by him. Critics highlight the title and the occasional examples of Western and Christian superiority but omit numerous examples that show how seriously he took Africans and their religious traditions. He said, “The Bantu are not savages”; “The Bantu are not simpletons.” He advised missionaries to treat local customs with respect and to master African languages.[12] Smith himself was offended by the title given to his book; he offered an apology in a later work and refused to sign a copy in New York twenty years later. Lower Races was replaced in 1929 by The Secret of the African, which followed the same general scheme and included summaries of beliefs in Africa south of the Sahara. Others, notably W. C. Willoughby, also studied African religion, and some researchers wrote about religion in specific areas (R. S. Rattray, E. E. Evans-Pritchard). In the 1920s and 1930s, however, Smith’s studies were prominent in publicizing the subject in popular and academic circles. His work was both wide-ranging and held together by an analytic framework. He used his fourfold schema (sometimes threefold, when the second and third terms, “souls” and “spirits,” were combined) throughout the interwar years. After World War II he incorporated more features, especially ritual and symbolism, drawn from anthropological and religious studies, as well as using information gathered during several long tours of southern Africa.

In the study of African religion Edwin Smith was followed by others whose names have become more famous than his: Placide Tempels and G. W. Parrinder, and Africans such as J. Mbiti and K. A. Dickson. Nevertheless, Smith’s work in publicizing this subject among anthropologists, missionaries, and students of religion in the 1920s and 1930s was vital for establishing African religion as a subject worthy of careful study. African religion had a very low profile in studies of comparative religion in those years, and he played a leading role in helping to provide a sufficient base of coherent knowledge for others to become interested in it.

Anthropology

Smith continued his involvement with anthropology after the publication of the ISP in 1920 and as he pursued his Bible society career. He had joined the Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI) in 1909, and from 1923, when he was based at the Bible House in London, he attended the RAI’s activities and became involved in its organizational structure. He was awarded the RAI’s Rivers Medal in 1930 and was frequently a member of its governing council in the 1920s and 1930s. The RAI elected him president for 1933-35, the only missionary ever to be so honored. His first presidential address, “Anthropology and the Practical Man” (1934), argued that anthropology is a useful subject for administrators, educators, and missionaries. He criticized missionary methods and considered that Africans could create a version of Christianity as worthy of Christ as anything produced elsewhere. The second presidential address, “Africa, What Do We Know of It?” (1935), was a monumental survey of the knowledge base in African studies at the time. He considered many aspects of Africa and suggested numerous lines of research. He had been interested in such developments for at least a decade, having helped to found, in 1926, the International African Institute, which was promoting such research. The 1935 address turned out to be very influential, and thereafter anthropologists were attracted to African topics. Sir Raymond Firth, secretary of the RAI at the time, told me that this address “did much to launch the systematic research interest in Africa which developed” after 1935.[13] Anthropologists, and those who use their research, owe a great debt of gratitude to Edwin Smith for turning their attention to Africa.

After retiring from the Bible Society, Smith taught African studies in the United States for five years (1939-44). This subject was badly neglected in those days. He spent four years at the Kennedy School of Missions, Hartford, Connecticut, where his attitude to Africa and its peoples left a deep impression on his students. Bill Booth, who studied Bantu linguistics at Hartford with him in 1943, mentioned Smith’s “sensitivity to cultural imperialism and his deep respect for African peoples and their cultures.” Booth observed that such “qualities, running against the current as they did, turned his students towards Africa with different expectations than they would otherwise have had.”[14]

Smith’s final year in the United States was spent at Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee. Fisk, a college for African Americans, impressed him by its multicultural approach, and he spent his time there encouraging the students to acquire a greater respect for their African heritage.

Respect for Africans

Smith left much that has benefited later generations. Behind his varied enterprises was a great respect for Africans. This attitude was remarkable because Africans were seldom treated with respect fifty or more years ago. Indeed, Smith claimed that when he began his work among the Ila, he regarded himself as vastly superior to them. Experience, however, changed his thinking, and he realized that he was often their inferior. He saw that they “were not essentially different from myself. Such unlikenesses as existed were mainly accountable to environment and tradition.”[15] He was always impressed by African languages, and in 1950 said, “I defy anyone to study a Bantu language thoroughly and retain an opinion that Africans are innately inferior to Europeans in intellect.”[16] Respect for Africans was evident in his anthropological studies, and a later observer, Elizabeth Colson, a professor of anthropology, observed that Smith and Dale “wrote of friends whom they respected as their equals.”[17]

Respect for Africans entered Smith’s discussion of race relations, and here his thinking could have developed in various ways. In the 1920s, when he was concerned that European influence would destroy African cultures, he toyed with the idea, common among anthropologists, that African societies should be preserved and, as far as possible, separated from European influence. He soon realized that this position would be undermined by European greed, which produced a grossly unfair distribution of land, so he abandoned separation as an approach to race relations. Instead his thinking, following J. H. Oldham and, more important, J. E. K. Aggrey, developed on the lines of cooperation. Aggrey, a Ghanaian who had lived in the United States, advocated cooperation as a basis for race relations, which Smith, who wrote Aggrey’s biography in 1929, took as his guiding principle. Respectful cooperation between cultures and subcultures conserves the past, maintains cultural integrity, and enables creative interactions. Smith offered his mature statement of these principles in his Phelps-Stokes Lectures given at Cape Town in 1949 and published as The Blessed Missionaries (1950). This was at the beginning of the apartheid era. Had his views been heeded, South Africa would have been saved from many years of racist domination. He held that South Africa would be deservedly admired by the whole world if it could establish “a community in which the several ethnical groups can live in harmony and co-operate for the common good”[18]; such thinking did not prevail in South Africa until forty years later.

Edwin Smith’s Legacy

Edwin Smith died on December 23, 1957, at Deal, England. What has he left future generations? Chiefly, there is respect for people, especially Africans, and their languages, cultures, and religions. He expressed this respect through copious writings that helped Westerners, especially Christians, gain a sympathetic understanding of Africans. He used social sciences in forming such a view and clearly learned much from Africans. His varied and integrated studies suggest that he imbibed the African sense of wholeness. His quest for cross-cultural understanding has profound implications in that painstaking efforts are needed to comprehend and perceive the varied perspectives of other cultures. Respect for Africans was behind his opposition to cultural imperialism, as rife in the twenty-first century as in his day. It was also behind his missiology of translation that allows people to express the Christian faith in forms they can own. Such matters need as much attention in the twenty-first century as in previous centuries because of our human tendency to impose our forms of thought and culture on others.

In Africa he was known as chitutamano, “the quiet wise spirit,” an apt description of Smith as a Christian missiologist and Africanist.

John Young

Notes:

-

Many sources give Smith’s middle name as Williams. I have been able to establish conclusively that it is William.

-

Edwin W. Smith, “Unpublished Reminiscences,” ca. 1957, Smith Papers, Methodist Missionary Society Archives, School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

-

Thabo died later in the year in Zambia. Their other child, Matsediso (“mother of consolation”), was born at Nanzhila on July 26, 1904.

-

Elizabeth Colson, introduction to The Ila Speaking Peoples of Northern Rhodesia, by Edwin W. Smith and A. M. Dale (London: Macmillan, 1920; reprint, 1968), p. 1.

-

See James Moulton Roe,* A History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1905-54* (London: British and Foreign Bible Society, 1965), p. 367.

-

William A. Smalley, Translation as Mission (Macon, Ga.: Mercer Univ. Press, 1991), pp. 67-68.

-

Edwin W. Smith, Knowing the African (London: Lutterworth Press, 1946), p. 18.

-

Edwin W. Smith, The Golden Stool (London: Holborn Publishing House, 1926), pp. 281-82.

-

Edwin W. Smith, Robert Moffat: One of God’s Gardeners (London: Student Christian Movement, 1925), The Mabilles of Basutoland (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1939), The Life and Times of Daniel Lindley (London: Epworth Press, 1949), and (about Roger Price) Great Lion of Bechuanaland (London: Independent Press, 1957).

-

W. John Young, “Edwin Smith: Pioneer Explorer in African Christian Theology,” Epworth Review, 1993, pp. 80-88.

-

M. Schofeleers, “Black and African Theology in Southern Africa: A Controversy Re-examined,” Journal of Religion in Africa, June 1988, p. 120.

-

Edwin W. Smith, The Religion of Lower Races (New York: Macmillan, 1923), pp. 6, 72, 74.

-

Letter to author from Sir Raymond Firth, June 28, 1994.

-

Letter to author from William R. Booth, June 18, 1993.

-

Edwin W. Smith, The Blessed Missionaries (Cape Town: Oxford Univ. Press, 1950), p. 136.

-

Ibid., 6.

-

Colson, Introduction, p. 6.

-

Smith, Blessed Missionaries, p. 142.

Bibliography

Major Works by Edwin W. Smith

(selected from thirty-five titles)

1907* Handbook of the Ila Language.* Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

1915 Ila New Testament (trans.). London: British and Foreign Bible Society.

1920 (with A. M. Dale). The Ila-Speaking Peoples of Northern Rhodesia. London: Macmillan.

1923 The Religion of Lower Races. New York: Macmillan.

1926 The Christian Mission in Africa. London: International Missionary Council.

1926 The Golden Stool. London: Holborn Publishing House.

1929 Aggrey of Africa. London: Student Christian Movement.

1929 The Secret of the African. London: Student Christian Movement.

1929 The Shrine of a People’s Soul. London: Church Missionary Society.

1936 African Beliefs and Christian Faith. London: Lutterworth Press.

1946 Knowing the African. London: Lutterworth Press.

1950 The Blessed Missionaries. Cape Town: Oxford Univ. Press.

1950 (ed.) African Ideas of God. London: Edinburgh House Press.

Archival materials on Edwin W. Smith are to be found in three locations: (1) The Methodist Missionary Society Archives, the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. These items include diaries, translation work, journalistic material, photograph albums, and some unpublished material. (2) Bible Society Archives, Cambridge, England. These items include diaries and reports for India, 1938-39, correspondence, and drafts of John 1-6 in Basic and Simplified English. (3) There is a relatively small collection of correspondence and other Smith papers in the Hartford Seminary Archives, Hartford, Connecticut.

Works About Edwin W. Smith

McVeigh, M. God in Africa: Conceptions of God in African Traditional Religion and Christianity. Cape Cod, Mass.: Claude Starke, 1974.

Peel, J. D. Y. “Edwin Williams Smith.” In Dictionary of National Biography, Missing Persons. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1993.

Young, W. John. “Edwin Smith: Pioneer Explorer in African Christian Theology.”* Epworth Review,* 1993, pp. 80-88.

—–.”The Integrative Vision of a Pioneer Africanist, Edwin W. Smith (1876-1957).” M.A. thesis, Univ. of Bristol, July 1997.

This article, is reproduced, with permission, from the International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Jul. 2001, Vol. 25, Issue 3, p. 126-130, copyright© 2001, edited by J. J. Bonk, R. T. Coote, D. J. Nicholas and G. H. Anderson. All rights reserved. The author, Reverend W. John Young, is a retired Methodist minister of Wellington, Somerset, England who served in Zambia, 1977-1982. He has written other articles and a book about Edwin Smith (e.g., The Quiet Wise Spirit: Edwin W. Smith [1876-1957] and Africa, Peterborough, Epworth Press, 2002), is interested in Primitive Methodist Missions and is involved in the Methodist Missionary Society History Project.

Photo Gallery