Classic DACB Collection

All articles created or submitted in the first twenty years of the project, from 1995 to 2015.Modi Din, Jacob

One of the pioneers and firsthand witnesses to the history of the church in Cameroon, Modi Din Jacob also contributed greatly to social development there. German colonization of Cameroon began in 1884, (when Modi was eight years old), interrupting the peaceful everyday life of all the ethnic groups in the country. Modi received a very good education early on in his life from the Basel Mission. His teenage and early adult years were spent under the German occupation, and he spent several years in prison around 1914-1916 after being unjustly accused of being a political activist. It was during this time of imprisonment that he became deeply impressed with his calling to pastoral ministry. From 1915 to 1917, he became a tireless evangelist to his people, the Sawa. When he heard of the need for missionaries to the interior, he answered the call. From that moment on, he became the Cameroonian missionary par excellence, unrivaled by any pastors from that region in his intercultural ministry. He was one of the few native missionaries who attracted the significant attention of mission historians. Who was this man from the Douala tribe, and why did all the people, including missionaries, pay such attention to what he did?

Childhood

Modi was born in 1876 in the village of Bonaduma in Douala. His father was a very important man who had six wives but only eight children. Modi’s mother, Muanjo, gave him four of those children. His family practiced the traditional ritual religion of the Douala. Four weeks after his birth, Modi was presented to the people and received a black mark on his forehead, the tattoo that was the mark of free men. His father died while he was still young, and his mother took over his training in religious practices as well as his general introduction to life.

Youth

Modi was ten years old when the Basel Mission arrived in 1886. They had been invited by the colonial government, which had established itself in Douala in 1884. He was one of the first students in the boys’ school that was opened by the mission, and he adapted quickly, being both intelligent and hard-working. The Bible story lessons were always of particular interest to him, and he happily related these newly discovered stories to his mother. His mother began to fear that he would move away from the practices of his ancestors, and encouraged him to concentrate more on learning arithmetic and to pay less attention to the stories the white people taught about God. He attended Sunday worship and catechism regularly, and was eventually baptized in secret, unbeknownst to his mother.

On the evening of his baptism, as he went home full of joy, his mother greeted him with insults and a beating, as the neighbors had told her about the event. She was so shocked by what he had done that she banished him for two days and refused to give him medical attention and food. Since her son stubbornly continued to hold to what he had chosen, she called on his grandmother to prepare a purifying potion that was supposed to neutralize the “magic drink” that he had taken during the baptism and cause him to vomit it back out. Modi refused to drink the potion and told his grandmother: “What I have received is not in my stomach, it is in my heart and in my blood.” [1]

In 1896, when he was twenty, Modi finished his studies in the German Middle School, which was equivalent to a ninth or tenth grade education in the French system, and he received the equivalent diploma. He had been in school for ten years, and now he needed to find work. His older brother had a thriving business on the Wouri River, and wanted Modi to come help him there, as he was now literate and adept at mathematics. To the great surprise of his family, Modi turned down the offer. He wanted to become a teacher. From that day on, he fell out of favor with his family. They harassed him continually because he had refused to reinforce their reputation as a rich and powerful family, but he never gave in.

Teacher

Modi had just gone through a period of intense pressure on the home front, so he went to the missionaries nearby for some encouragement. Some emissaries from the village of Bonamakembe, who had just come to the mission station to ask for a teacher, were surprised by his arrival. Without hesitation, the missionaries acceded to their request and offered to give them Modi as a teacher. The emissaries happily accepted him and took him back to their village. Modi was happy too, because he did not want to go back home to say good-bye to his family. The way it happened made Modi feel that God had planned it, and his presence was a source of great joy to the people of Bonamakembe.

Students enrolled, and Modi began to teach the classes. In addition to teaching, he went to visit people in their homes, and also started a Sunday worship service. His gifts as an evangelist were noticed right away. He also showed his love for the people by defending them from shady Douala merchants who took advantage of them. These merchants scorned the people there and treated them like ignorant and uncultured bushmen. His opposition to this behavior, which came from his own Douala people, earned him the trust of all the locals. In addition, the Douala openly wondered how it could be that one of their own could prefer another people to them.

After having spent two and a half years in Bonamakembe, Modi was brought back to the Bonanjo School in Douala, where the palace of King Rudolph Douala Manga Bell was located. There was still no girls’ school in Douala at that time. Modi taught in the Bonanjo School from 8 a.m. to noon, and from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. On his own, he began to offer classes for girls, from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. He started out with ten girls, but there were soon one hundred.

His family continued to harass him and to pressure him to quit his miserable work as a teacher so that he could work for the family business and make a lot of money. However, Modi remained steadfast in his faith and resisted all the temptations and possibilities extended to him by his family as they tried to turn him away from his vocation.

It was at this time that he got married, and this decisive step in his life also brought about many problems related to his choice of a wife and the significant dowry he needed. Once again, he had to show firmness of character and resolution in his faith.

Pastoral Ministry

In 1905, Modi was transferred to the Girls School in Bonaku, which was also where the home office of the mission was located. His work took place all over Douala, and he served Christians and non-Christians alike. On Sundays, he went to the surrounding Bassa churches. When Pastor Deibol died, the churches of Bonaduma and Bonapriso were put in his care. He underwent pastoral training and was ordained on December 3, 1912, by the director of the Basel Mission to Cameroon, Pastor Lutz. The ceremony was held in the church at Bonaduma, and the text for the sermon was John 21: 15-18, (“Feed my sheep.”)[2] These words became the solid rock of his faith, and he often turned to them for comfort in the difficult times of his ministry. He fulfilled his calling in body and soul, and served the country churches around Douala that he was charged with.

He was faithful to his family and his love for them was always made manifest. Members of his family were so affected by this love that some were eventually baptized, and so he won them over. His own mother, who was near death at the time, thanked him for his faithfulness and perseverance, and told him: “If you had not been so firm when you were a small boy, and if you had allowed us to turn you away from your faith, I would have died today as a pagan, in fear and anguish. But now I can die rejoicing, because I know that I am going to be with my Savior, and that I will see you all there once again.”[3]

Prisoner of the Colonial Government

Very early in his life, because of his own family, Modi had gone to the school of suffering that often serves as preparation for men of God who need to learn to learn about death and perseverance in the faith. When the First World War began, the colonial government suspected that Modi and many other influential men in Douala were involved in political activities. The administration tried to get Modi to use his influence with the Douala people in order to convince them to leave the Joss plateau, as they wanted to build a European city there. Having come up against his refusal to do their bidding, they instigated a trumpery quarrel with him. He was put under guard, and as soon as the war began, he was arrested and transferred to the military tribunal of Sopo in Buea, where he had to prove his innocence. Although he was acquitted by the judge there, he was not freed. He was kept as a hostage and transferred to prisons in the interior at Abong Bang and Akonolinga, and then on to Yaoundé. Altogether, he spent twenty months in prison. He spent the time reading his Bible in depth and meditating on what he read. The words he meditated on kept him from despair and became the foundation of future projects in his ministry. Both his attitude and his calm and assured manner made quite an impression on the prisoners and the guards, and even the townspeople. They all attributed his behavior to supernatural forces.

Late one night, an army of red ants invaded the prison compound. Modi had been suffering from a bout of malaria and was running such a high fever that his body was shaking. The guard had offered to let him come out of his cell, but Modi had refused the offer, thinking that if the guard’s benevolence were discovered, he would be severely punished or might even lose his job. The prisoners all woke up noisily, jumping up and down to try to get rid of the ants. In the morning, there were large groups of ants here and there, so many that in certain places, they blocked the way. Unable to reach Modi to check on his condition, the desperate guard began to think that he must surely be dead. He regretted not having let Modi out of his cell the night before, and gave up trying to reach Modi’s cell because he didn’t want to see the man of God eaten by the ants. Someone else tried to make his way to the cell, running all the while, to avoid being stung by the ants. He cried out to Modi, to see if he was still alive. Everyone was stunned when they heard him answer “yes.” What had he done to escape the ants? It seems that his temperature had been so high that his body had simply been covered in sweat all night, and that even though he was asleep, the ants could not attack him. Modi had also had a dream in which he overcame a certain difficult situation. When he woke up, he understood what God had done.

Modi led some of the people in prison to faith. Some Make chiefs had been arrested and condemned to death because a Hausa had been killed in their territories and the body had never been found. The authorities knew that some of those tribes practiced cannibalism and that they could have killed him and eaten him, so they threw the chiefs in prison to await confirmation of their sentence. The Make chiefs were very much afraid of death, but when they saw how hopeful Modi looked even after he had been in prison for so long, they thought he must have a fetish or that he must be a witchdoctor. They were amazed that Modi had not been executed after such a long stay in prison. They asked him to give them his fetish so that they too would escape their sentence. Modi’s answer was that his fetish was the Word of God. He spoke to them about the love of God and about the life of Jesus, from his birth to his death and resurrection. They were amazed that this was all that Modi had by way of protection, and they secretly thought to themselves that he must have a fetish. Modi asked them to reveal why they had been condemned to death and why they wanted his fetish. The oldest of the four chiefs admitted that they had killed the Hausa and had eaten him, but that they could not admit this to anyone. Modi helped them to understand these words of Jesus: “He who believes in me will live, even though he dies, and he who lives and believes in me will never die.” He helped them to receive Jesus into their hearts. When the sentence of death was announced, they went to their execution without fear or embarrassment. They said their goodbyes to their companions, with shining eyes full of peace.

After the execution, the white man who was in charge came to find Modi and reprimanded him severely with these words: “Who told you to change the governor’s sentence? What have you done to make these people go to their death so peacefully? The governor didn’t send you here as a pastor, but as a prisoner! If this happens again, I’ll hang you.” [4] Those words proved that the Make chiefs had kept the faith to the end.

Evangelist during the interim period

In the period of time between the capitulation of Germany and the division of Cameroon by France and Great Britain, Modi carried out a significant evangelization campaign among his own ethnic group, the Sawa. He undertook this ministry without thinking of how he might be paid. Even his own people thought that with the War, the mission work would also come to an end. They sent messengers to help him find work that would provide for his daily bread. This was Modi’s answer: “While I was in captivity I had enough time to think about what I would do, with God’s help, when I went back home. I promised God that I would do nothing but preach the Gospel. The mission is not dead as you may think. Even though missionary work had to stop during the War, it doesn’t mean that things will go on being like that.” [5] Modi agreed with Pastors Ekollo and Kuo that they would work in the city of Douala and the immediate area, and that he would go to the churches in the interior to reassemble, strengthen and encourage the Christians there. This is how he came to travel the paths in Malimba, Bakoko, Edea and Sakbayeme, and the paths along the Sanaga and the Wuori rivers, as well as the paths in Longsi and the paths near the railway line leading north all the way to Nkongsamba.

In 1917, Modi wrote the following letter to a missionary named Rhode de Buea, on the subject of his evangelism campaigns:

As far as my travels for the work of the Lord, I must say that they are not useless. In the entire region around Douala, one can often hear people saying, “The Basel Mission is dead; we destroyed it.” This is why many Christians have been weak. They have been troubled, and haven’t known what to do anymore. While visiting the villages near Longasi, my heart was pained to see that almost all the Christians had returned to pagan practices. But God be praised - He who works in the hearts of men so that when I arrive, they come to me, they feel the consequences of what they have done wrong, they confess their sin and want to start a new life in Jesus. They accept my exhortations and listen to me. This takes up so much of my time that I can hardly think of doing anything else. And yet, it seems to me that it is both necessary and urgent to visit these bush churches, and I feel that God is with me. I teach the people to cling to God, to He who gave His Son as a ransom for our sins, and to He who gives us the promise of eternal life if we believe in Him with all our heart. I can attest that the Spirit of God is at work among them, drawing them to Him. He does this because I take care of them and visit them from time to time. [6]

Missionary to the Tribes of the Interior

Modi not only carried out a far-reaching work of evangelization, he was also a great missionary to the tribes of the Interior: the Bamoun, the Bamileke, the Bameta and the Bakongwa in the Bamenda region, and in Bao-Balondo in the Buea zone. In some years, he spent less than two weeks at home, and in eight months he could make three round trips (that amounted to 3,000 km). His wife supported him valiantly in all that work and encouraged him in it. This is what is written about his wife: “For example, on two separate occasions, one of their children died while their father was away. One of them was eleven years old when [he] died in 1918, and another died in 1924, being only nine months old at the time. The proof of her heroic attitude and of her faith can be found in a letter that she wrote to her husband: ‘Our small one is very sick. As far as I can tell, the Lord will take him back soon. But don’t come back home because of that; continue on with your trip. The Lord is with us.’” [7]

The Impact of His Faith in Society

The region where Modi worked as evangelist and missionary encompasses the present provinces of the Coast (County Seat: Douala), the South-West (County Seat: Buea), the West (County Seat: Bafoussam) and the North-West (County Seat: Bamenda). Because of his work, three denominations have been formed: The Evangelical Church of Cameroon, the Union of Baptist Churches of Cameroon, and the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon. Most of the believers from these denominations live in those areas, and all together, they account for at least two million church members.

Robert Amadou Pindzié

Notes:

-

Grob p. 10.

-

Grob p. 12.

-

Grob p. 13.

-

Grob pp. 20-21.

-

Grob p. 28.

-

Grob pp. 30-31.

-

Grob p. 32.

Bibliography

Frank Christol, Quatre ans au Cameroun [Four Years in Cameroon] (Paris: Evangelical Mission Society of Paris, 1922).

Francis Grob, Témoins Camerounais de l’Evangile (Les origines de L’Eglise Evangélique) [Cameroonian Witnesses to the Gospel (The Origins of the Evangelical Church)] (Yaoundé: Editions CLE, 1967).

Alexandra Loumpet-Galitzine, Njoya et le royaume Bamoun. Les archives de la Société des Missions Evangéliques de Paris [Njoya and the Bamoun Kingdom. Archives of the Evangelical Mission Society of Paris] (Paris : Editions Karthala, 2006).

Scheibler, Paul, Was die Gnade Vermag: Aus dem lebe des negerpfarres Modi Din in Kamerun (Stuttgart and Basel: Evang. Missionsverlag. Gmbh, 1931).

Jean-Paul Messina and Jap Van Slageren, Histoire du Christianisme au Cameroun, des origins à nos jours, Approche oecuménique [The History of Christianity in Cameroon From its’ Origins to the Present, an Ecumenical Approach] (Yaoundé : Editions Karthala, Paris, and Editions CLE, 2005).

Jap Van Slageren, Les origines de l’Eglise Evangélique au Cameroun. Missions et christianisme autochtone [The Origins of the Evangelical Church in Cameroon. Native Christianity and Mission] (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972).

This article, received in 2008, was written and researched by the Rev. Robert Amadou Pindzié. Rev. Pindzié is a professor in the Evangelical Seminary of Cameroon in Yaoundé, and was the Project Luke scholar for 2007-2008.

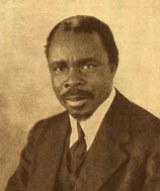

Photo Gallery

[1] Modi Din with missionaries.

[1] Modi Din with missionaries.

[2] Modi Din in prison

[2] Modi Din in prison